September

21, 2023

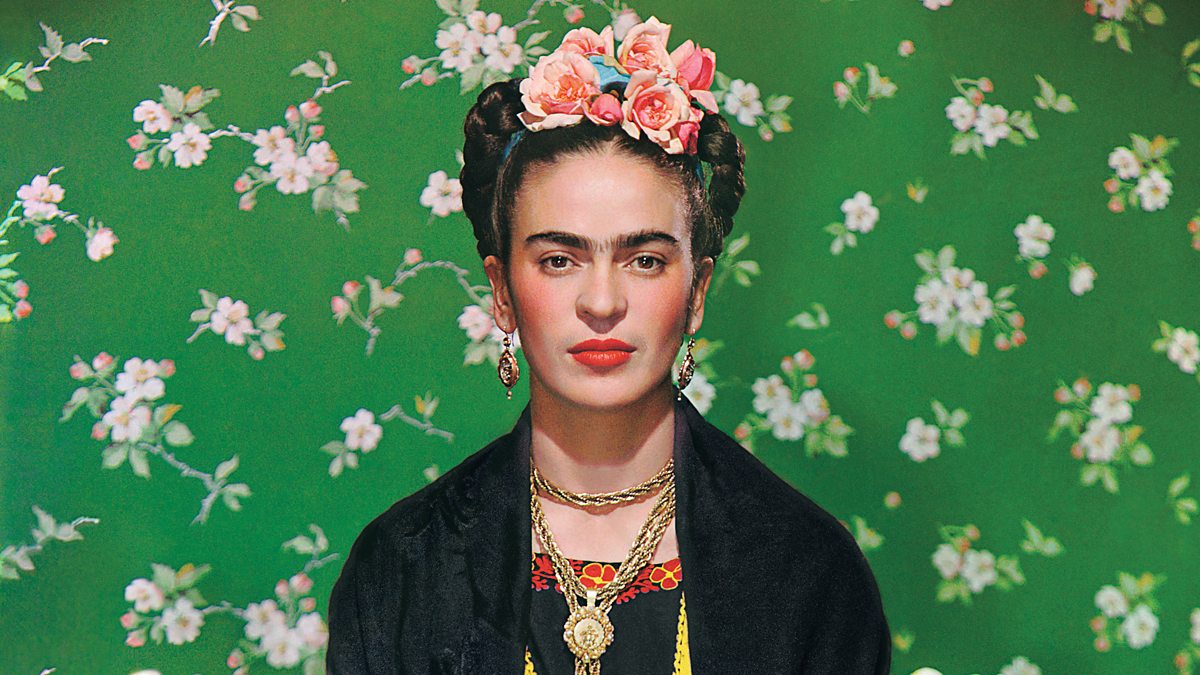

Frida

Kahlo was born in 1907, three years before the Mexican Revolution. As a

teenager, she attended the National Preparatory School in Mexico’s capital,

where she excelled in anatomy and looked forward to medical school and becoming

a physician. But in 1925 her goal was sideswiped by a trolley that crashed into

the rickety wooden bus that she regularly took home from school. On impact, the

tram’s iron handrail impaled her spinal column and exited her vagina,

shattering spine and pelvis. She lived with the aftereffects of the accident

for the rest of her life.

Frida

(commonly known by her first name, like Beyoncé) was not expected to live. She

defied the doctors just as she would defy social conventions. Her study of

anatomy would prove serendipitous. In her convalescence, the bedridden would-be

doctor began sketching, often using herself as a model. Her paintings, most

small as a sheet of computer printing paper, have an outsize impact on the

viewer, on Mexican identity and on modern art.

“Becoming

Frida Kahlo,” Louise Lockwood’s three-part BBC miniseries that airs on PBS

starting this week, is strong on sociopolitical context and archival research.

Visually, the documentary comes alive when it focuses on Frida’s vivid

portraits or on photographer Nikolas Muray’s lush color studies of the artist,

erotic as Hollywood glamour shots. In this, the documentary is Frida for the

Instagram age. Emotionally, it connects when Cristina Kahlo, Frida’s

great-niece, or Juan Coronel Rivera, grandson of Frida’s husband, muralist

Diego Rivera, talk about their storied antecedents. Art historian Luis-Martin

Lozano, and Kahlo biographers Hayden Herrera and Martha Zamora provide insights

into Frida’s life and work.

Over

three episodes, Lockwood succeeds in tracing the arc of her subject’s life and

identifying several of Frida’s Who’s Who of lovers. They include Soviet

revolutionary Leon Trotsky and American painter Georgia O’Keeffe.

While

the cradle-to-grave narrative is a good introduction to Frida’s life, those

familiar with her art will note that the documentary is more focused on her

biography and secular sainthood than her work. The occasionally glib narration

— “art was Frida’s superpower” — and clichéd, oversimplified summaries — “From

the beginning, Frida’s work is about herself, exorcising her demons” — do its

subject an injustice.

Just

because she figures in many of her paintings does not mean they are only about

herself. Often, her self-portraits are portraits of Mexico. Like her country,

Frida was mezcla, a mix. Her father was German; her mother Oaxaca-born, of

Indigenous and Spanish parentage. Like many female artists throughout history,

Frida had a father who was himself an artist. Guillermo Kahlo, an architectural

photographer, recruited Frida to color-tint his prints by hand.

While

the miniseries looks at “The Two Fridas”(1939), it fails to bring us into the

painting. At 5 ½ x 5 ½ feet, it is one of her largest works. In it, she

wrestles with the political connections and tensions of her European and

Indigenous heritages. At the same time, the allusive canvas likewise wrestles

with her feelings about her tumultuous marriage to, and separation from, Diego

Rivera. (She loved him madly, and vice versa, but he couldn’t resist other

women. These included her sister, Cristina, Mexican-born Hollywood actress

Dolores del Rio and the ebullient film star Paulette Goddard.)

In the

stunning double self-portrait, the Frida on the left wears a lace-embellished

European wedding dress. The Frida on the right is clad in an iris-blue and

sunflower-yellow huipil, the tunic favored by Indigenous women since the 10th

century. The two Fridas clutch hands. Over the left breast of each is an

exposed heart and a tangle of arteries connecting the pair. Euro-Frida’s heart

is broken; Indigenous Frida’s heart is intact. Euro-Frida holds scissors in one

hand and has severed an artery leaving blood splatters on her dress. Indigenous

Frida sits proud and strong, clutching a tiny portrait of Diego in her hand.

Forgive

me. It’s unfair to criticize a movie — or a painting or a book — for what is

not there. To its credit, “Becoming Frida Kahlo” does pause to consider

“Self-Portrait at the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States.”In this

mordant 1932 work, the sun and moon hover above a pre-Columbian temple on the

Mexico side, and blooming dahlias are rooted in the soil. On the U.S. side, the

stars-and-stripes flies over smokestacks and turbines, and instead of

vegetation, electrical machinery is plugged into the ground. In the center of

it all stands Frida, clutching a Mexican flag, indicating her preference for

culture and cultivation over industrialization. Frida’s work could be

immediately understood both by the illiterate and the educated.

In

their native country, Frida and Diego were embraced as proponents of

mexicanidad, a cultural crusade celebrating Mexican identity. When Andre

Breton, the French author of the Surrealist manifesto, met Frida, he pronounced

her one in his transnational movement. This one-woman zeitgeist was her own

movement, the maker of self-portraits that were at the same time political

allegories. The documentary likewise purveys her canvases frankly depicting her

physical pain. One is “The Broken Column” (1944), painted after one of her many

surgeries. She shows herself in a surgical corset, a shattered Doric column in

place of her spine, nails piercing her torso as if to keep the column in place.

Did painting it give her reprieve, however brief, from physical agony?

A

brief digression from the documentary for a related point. About the time of

Frida’s centenary, I was at a folk-arts gallery purveying handcrafted ceramics

and jewelry. A colorful amulet in the case caught my eye. I asked the owner if

its female likeness was Shiva, the Hindu deity of transformation. “It’s from

India,” she said, “but it’s Frida.” Somewhere on the Asian subcontinent, an

artisan had beatified the Mexican painter as a transformer of pain. That brand

of identification, spoken of as “Fridamania” or “Fridolatry,” was mostly a

posthumous embrace of her work.

Frida

predeceased the ailing Rivera by three years. He sold most of his and her

available work to his patron, Dolores Olmedo, not exactly an admirer of Frida

or her art. For a generation, Frida’s legacy went into eclipse. North of the

Mexican border, Frida was resurrected by two affirming forces: Latina artists

such as muralist Judy Baca who paid tributes to her in the 1960s and 1970s, and

Hayden Herrera’s 1983 biography.

Years

ago, Baca observed that “Frida unified Europeanized Mexico with pre-Columbian

Mexico in the way that Guadalupe, “the brown Virgin,” unified European

Christianity with Indigenous beliefs in Mexico.” That’s a keen summation of the

artist’s superpower. Although not quite as sophisticated, the documentary’s

conclusion speaks to those encountering Frida for the first time. As Frida

biographer Martha Zamora observes, “Whoever opens a door or a window, opens it

for everyone. And Frida opened it for a lot of artists.”

No comments:

Post a Comment