March

25, 2024

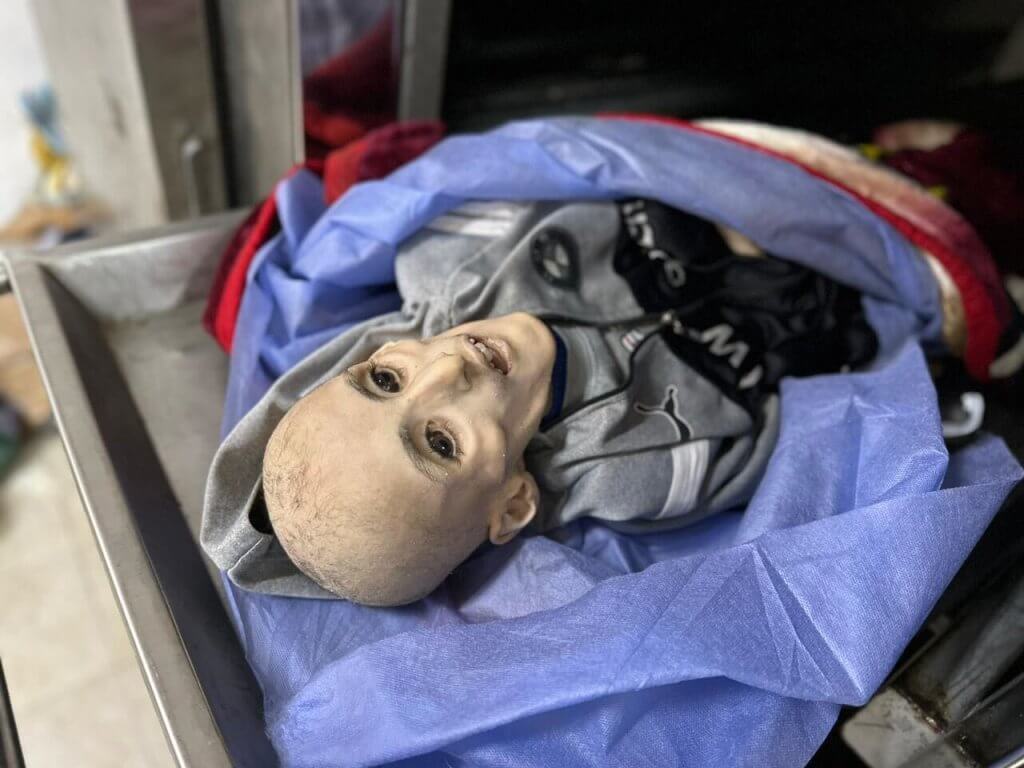

This

is not a photo of a mummy or an embalmed body retrieved from one of Gaza’s

ancient cemeteries. This is a photo of Yazan Kafarneh, a child who died of

severe malnutrition during Israel’s genocidal war on the Gaza Strip.

Yazan’s

family now lives in the Rab’a School in the Tal al-Sultan neighborhood in Rafah

City. His father, Sharif Kafarneh, along with his mother, Marwa, and his three

younger brothers, had fled Beit Hanoun in northern Gaza early on in the war.

Yazan

Kafarneh died at the age of nine, the eldest of four brothers — Mouin, 6,

Ramzi, 4, and Muhammad, born during the war in a shelter four months ago.

Living

in conditions not fit for human habitation, the grieving family had witnessed

Yazan’s death before their eyes. It didn’t happen all at once but unfolded

gradually over time, his frail body wasting away one day after another until

there was nothing left of Yazan but skin and bones.

Sharif

was unable to do anything for his son. He died due to a congenital illness that

required a special dietary regimen to keep him healthy. Israel’s systematic

prevention of food from reaching the civilian population in Gaza meant that

severe malnutrition — suffered by most children in the besieged enclave — in

the case of Yazan meant death.

“We

first left from Beit Hanoun to Jabalia refugee camp,” Sharif told Mondoweiss.

“Then the occupation called us again and warned us against staying where we

were. So we left for Gaza City. Then, the occupation forced us to flee further

south, and we did.”

Sharif Kafarneh’ (left), his wife Marwa (right), and their three

surviving sons (center) in their shelter in Rafah. (Photo: Tareq

Hajjaj/Mondoweiss)

“If

it weren’t for Yazan, I would have never left my home,” Sharif maintained.

“Yazan required special care and nutrition.”

Yazan

suffered from a congenital form of muscular atrophy that made movement and

speech difficult, but Sharif said that it never caused him much grief in his

nine short years before the war.

“He

just had advanced nutritional needs,” Sharif explained. “But getting that food

for him was never an issue before the war.”

It

was a point of pride for Sharif that he, a taxi driver, had never left his

child wanting or deprived.

“That

changed in the war. The specific foods that he needed were cut off,” he said.

“For instance, Yazan had to have milk and bananas for dinner every day. He

can’t go a day without it, and sometimes he can have only bananas. This is what

the doctors told us.”

“After

the war, I couldn’t get a single banana,” Sharif continued. “And for lunch, he

had to have boiled vegetables and fruits that were pureed in a blender. We had

no electricity for the blender, and there were no fruits or vegetables

anymore.”

As

for breakfast, Yazan’s regimen demanded that he eat eggs. “Of course, there

aren’t any more eggs in Rafah City,” Sharif said. “No fruits, no vegetables, no

eggs, no bananas, nothing.”

“But

our child’s needs were never a problem for us,” Sharif rushed to add. “We loved

taking care of him. He was the spoiled child of the family, and his younger

brothers loved him and took care of him, too. God gave me a living so I could

take care of him.”

Due

to his special needs, charitable societies used to visit Yazan’s home in Beit

Hanoun before the war, providing various treatments such as physical therapy

and speech therapy. All in all, Yazan had a functional, happy childhood.

‘He

got thinner and thinner’

The

family continued to take care of Yazan throughout the war. They tried to make

do with what they could find, trying as much as possible to find alternatives

to the foods Yazan required. “I replaced bananas with halawa [a tahini-based

confection], and I replaced eggs with bread soaked in tea,” Sharif said. “But

these foods did not contain the nutrients that Yazan needed.”

In

addition to his nutritional needs, Yazan had specific medicines to take. Sharif

used to bring him brain and muscle stimulants that helped him stay alive and

mobile, allowing him to move around and crawl throughout their home. Those

medicines ran out during the second week of the war.

With

the lack of nutrition and medication, his health took a turn for the worse. “I

noticed him getting sick, and his body was becoming emaciated,” Sharif

recounts. “He got thinner and thinner.”

His

family took him to al-Najjar Hospital in Rafah, where his health continued to

deteriorate over the course of eleven days.

“Even

after we took him to the hospital, they couldn’t do anything for him,” Sharif

continued. “All they were able to give him were IV fluids, and when his

situation got worse, the hospital staff placed a feeding tube in his nose.”

“My

son required a tube with a 14-unit measurement, but all the hospital had was an

8-unit,” he added.

When

asked what was the most important factor that led to the deterioration of his

son’s condition, Sharif said that it was the environment he lived in. “Before

the war, he was in the right environment. After, everything was wrong. He was

in his own home, but then he was uprooted to a shelter in Rafah.”

“The

situation we’re living in isn’t fit for humans, let alone a sick child,” Sharif

explained. “In the camps, people would light fires to keep themselves warm, but

the smoke would cause Yazan to cough and suffocate, and we weren’t able to tell

them to turn their fires off because everyone was so cold.”

Dr.

Muhammad al-Sabe’, a pediatric surgeon in Rafah who works at the al-Awda,

al-Najjar, and al-Kuwaiti hospitals, took a special interest in Yazan’s case.

“The

harsh conditions Yazan had to endure, including malnutrition, were the main

factors contributing to the deterioration of his health and his ultimate

death,” Dr. al-Sabe’ told Mondoweiss. “This is a genetic and congenital

illness, and it requires special care every day, including specific proteins,

IV medicines, and daily physical therapy, which isn’t available at Rafah.”

Dr.

al-Sabe’ said that most foods administered to patients who cannot feed

themselves through feeding tubes are unavailable in Gaza. “The occupation

prevents these specific foods and medicines from coming in,” he explained.

“Including a medicine called Ensure.”

Ensure

is a special nutritional supplement used in medical settings for what is called

“enteral nutrition” — feeding patients through a nasal tube.

“Special

treatment for patients, especially children, is nonexistent,” Dr. al-Sabe’

added. “We don’t even have diapers, let alone baby formula and nutritional

supplements.”

“If

things don’t change, if they stay the way they are, we’re going to witness mass

death among children,” he stressed. “If any child doesn’t receive nutrition for

an entire week, that child will eventually die. And even if malnourished

children are eventually provided with nutrition, they will likely suffer

lifelong health consequences.”

“If

medicine is cut off from children who need it for one week, this will also

likely lead to their death,” he continued.

Children

disproportionately affected by famine

According

to a UNICEF humanitarian situation report on March 22, 2.23 million people in

Gaza suffer at least from “acute food insecurity,” while half of that

population (1.1 million people) suffers from “catastrophic food insecurity,”

meaning that “famine is imminent for half of the population.”

An

earlier report in December 2023 had already concluded that all children in Gaza

under five years old (estimated to be 335,000 children) are “at high risk of

severe malnutrition and preventable death.” UNICEF’s most recent March 22

report estimates that the famine threshold for “acute food insecurity” has

already been “far exceeded,” while it is highly likely that the famine

threshold for “acute malnutrition” has also been exceeded. Moreover, UNICEF

said that the Famine Review Committee predicted that famine would manifest in

Gaza anywhere between March and May of this year.

Dr.

al-Sabe’ stresses that such dire conditions disproportionately affect children,

who have advanced nutritional needs compared to adults.

“Their

bodies are weak, and they don’t have large stores of muscle and fat,” he

explained. “Even one day of no food for a young child will lead to consequences

that are difficult to control in the future.”

“An

adult male may go a week without food before signs of malnutrition begin to

show,” he continued. “Not so with children. Their muscle mass increases

whenever they eat, which in turn leads to a greater need for nutrients.”

The

lack of nutrients means that children will grow weak, the pediatric surgeon

said, and that they will quickly begin to exhibit symptoms such as fatigue,

sleepiness, diarrhea, vomiting, anemia, sunken eyes, and joint pains. For the

same reason, Dr. al-Sabe maintained, children also respond to treatment fairly

quickly — but “on the condition that they have not experienced malnutrition for

more than a week.”

After

one week, reversing the effects of malnutrition becomes much more difficult.

Al-Sabe’ asserts that children’s digestive tracts will slow down, they might

begin to suffer from kidney failure, and their bellies can swell with fluids.

That

is what is particularly devastating for Gaza — over 335,000 children have

undergone varying degrees of extreme malnutrition for months on end. The

consequences are difficult to fathom on a population-wide level and for future

generations. As of the time of writing, over 30 children have already died due

to malnutrition in northern Gaza, but the real number is likely much higher

given the lack of reporting in many areas in the north.

‘He

didn’t need a miracle to save him’

Yazan’s

mother, Marwa Kafarneh, could barely contain her tears as she spoke of her son.

“He

was a normal boy despite his illness,” she told Mondoweiss. “He played with his

brothers. He crawled and moved about, and he could open closets and use the

phone, and he would watch things on it for hours.”

“He

could have lived a long life, a normal life,” she continued. “His father would

have brought him everything that he needed. He wouldn’t have had to feel hungry

for even a single day.”

When

she saw that the images of her son’s emaciated body had gone viral on social

media, Marwa said that she preferred death over looking at the photos. “My

eldest son died in front of my eyes, in front of all of our eyes,” she said.

“We weren’t able to save him. And he didn’t need a miracle to save him either.

All he needed was the food that we’ve always been able to provide for him.”

Reflecting

as she cried, she added: “But finding that food in Gaza today takes nothing

less than a miracle.”

No comments:

Post a Comment