John Ross

(This is an

edited version of an article which originally appeared in Chinese at

Guancha.cn.)

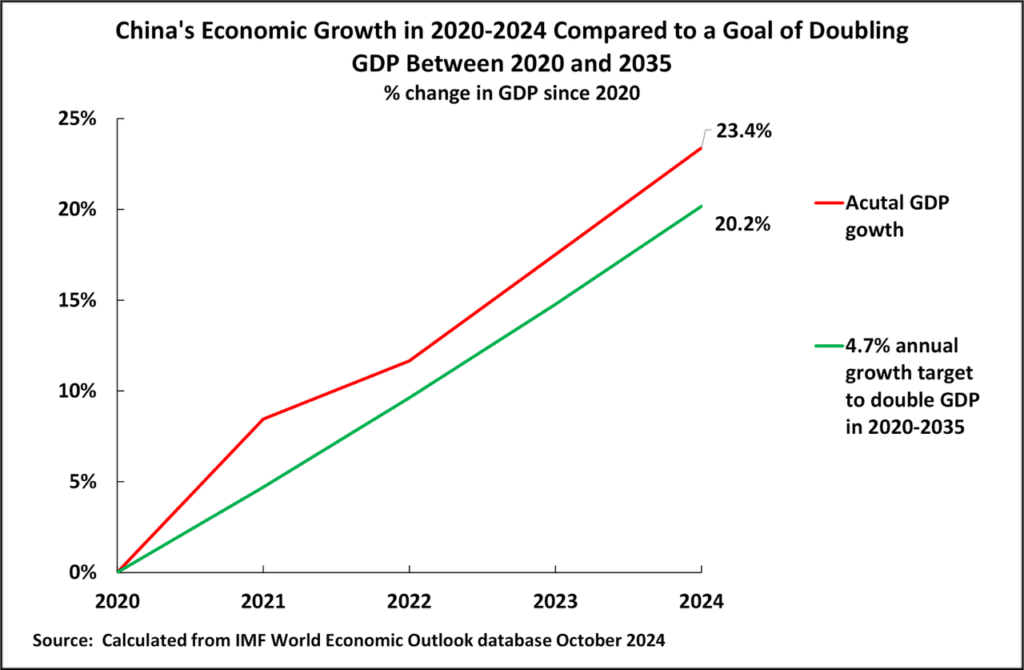

China’s GDP

growth of 5.0% in 2024 meant it successfully hit its GDP goal of “about 5.0%”

for the year. More significantly for China’s strategic economic development,

Figure 1 shows that it means its economic growth continues to be ahead of the

target discussed at the time of the adoption of the 14th Five Year Plan of

doubling GDP between 2020 and 2035.1

Such a goal

requires an average 4.7% annual GDP growth rate in 2020-2035. This, therefore,

meant that by the end of 2024 China’s economy should have grown by 20.2%

compared to 2020. Figure 1 shows that the actual result was that China’s

economy grew in this period by 23.4%—exceeding that target.

In summary. in

terms of its China’s domestic goals in 2024, it achieved both those for that

year and in terms of its strategic objectives.

China’s economic

performance in international comparison

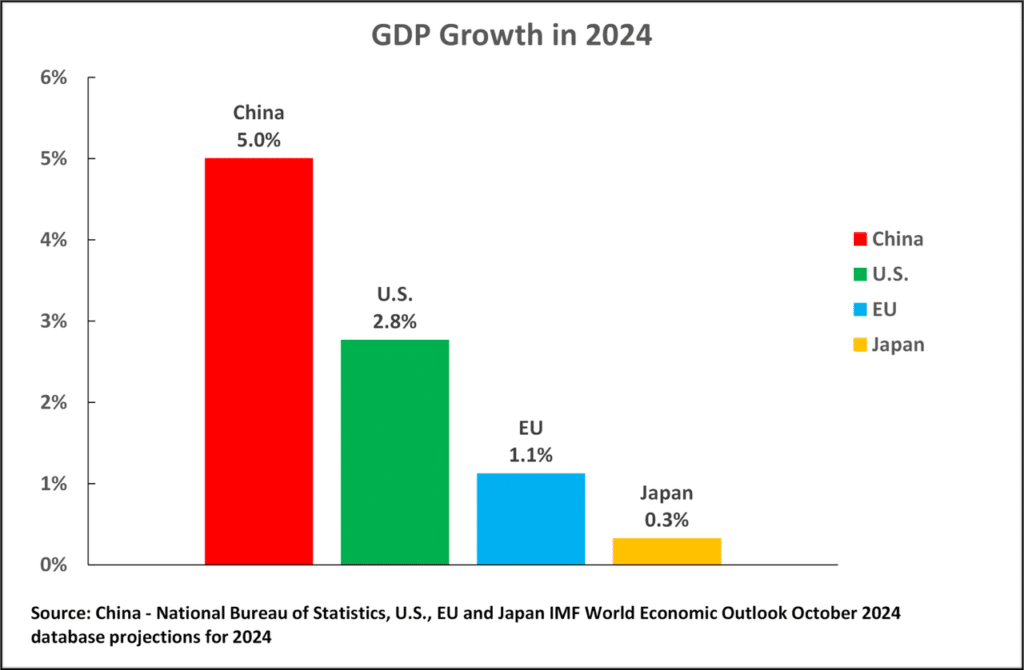

Turning to

international comparisons, Figure 2 therefore shows GDP growth in 2024 for the

major economic centres—China and the U.S. figures being the actual results and

those for the EU and Japan being the IMF’s projection for full year growth

based on the first three quarters results. As may be seen China’s GDP growth of

5.0% compares to the U.S.’s 2.8%, the EU’s 1.1% and Japan’s 0.3%. On that data,

China’s GDP growth rate in 2024 was therefore 80% higher than the U.S., four

and a half times as fast as the EU and over sixteen times as fast as Japan.

Doubtless, when the final figures are published, details of these comparisons

will change slightly but the gaps are clearly far too wide to change the

fundamental comparisons—China’s economy in 2024 outperformed by a huge margin

the other major economic centres. A picture completely opposition to the false

claims of the Western media throughout the year such from The Economist that

the U.S. is “leaving its peers ever further in the dust,” or from the Wall Street

Journal describing China as having “a stagnant economy.” It is irrelevant

whether such claims are deliberate lies, propaganda distortions, or failures to

investigate the facts. In any case, they are falsifications which have nothing

to do with serious journalism. It confirms that the great majority of the

Western media is simply a tool of propaganda with nothing to do with objective

attempts to find and report the facts.

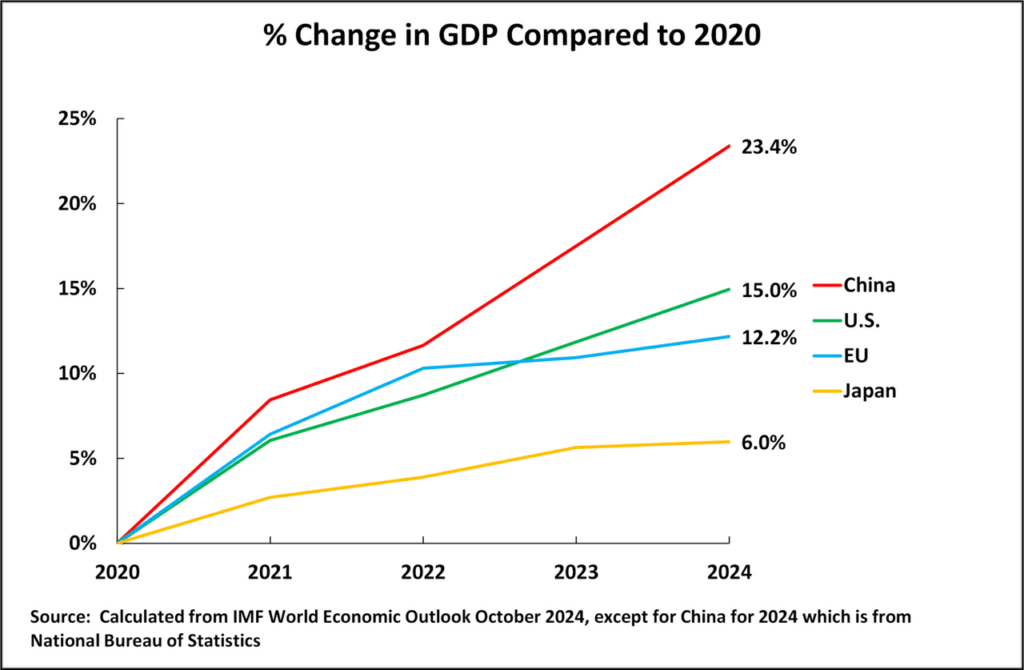

Turning to

looking at the major economic centres in terms of comparison to China’s

strategic economic targets in 2020-2035, using the same data, Figure 3 shows

that over the period 2020-2024 China’s total GDP growth was 23.4%, the U.S.

15.0%, the EU 12.2%, and Japan 6.0%. In short, China’s economy was far

outgrowing the U.S. and the other major economic centres not only in 2024 but

in the entire period since China set its strategic economic goals.

China’s

qualitative development

This data

evidently makes clear that the tariffs, sanctions and other measure introduced

by the U.S. since Trump began this process in 2018 etc have been

unsuccessful—China’s economy has continued to far outgrow the U.S.. The reasons

for this will become clear below—which in turn will also clarify what are the

decisive issues for China to achieve its strategic 2035 goal. Before doing

this, however, it is worth making an overall assessment of China’s strategic

progress not only in quantitative but in qualitative terms. Regarding this,

rather than the present author, who for several decades has been analysing

China’s success, having to do this, it is sufficient to quote at length an

anti-China source which therefore cannot be accused of exaggerating positive

assessments of China—The Economist magazine. The Economist, despite its

determination to attack China had to admit realities. Under the

self-explanatory headline of “the consequences of success” it noted in January

regarding China’s qualitative progress:

“The goal was to

turn China into a green and innovative “manufacturing power”, one that relied

less on labour and Western supply chains, and more on automation and new

home-grown technologies. This was Xi Jinping’s vision for the Chinese economy.

“It has, for the

most part, been a resounding success. Aided by the government, Chinese firms

have risen to the very top of some industries. They have grown more automated

and sophisticated. The torrent of goods coming from Chinese factories… resulted

in a record trade surplus of nearly $1trn in 2024…

“More

impressive, though, has been China’s performance in fields deemed important by

the state.

“Two of the

clearest examples are electric vehicles (EVs) and drones. The plan called for

Chinese companies to sell 3m of the former in 2025. That shouldn’t be a

problem: they sold more than 10m last year, accounting for nearly two-thirds of

the global total. In the last quarter of 2024 China’s biggest EV-maker, BYD,

surpassed Tesla, an American firm, in worldwide sales of battery-only cars.

China’s biggest drone-maker, DJI, is even more dominant. Its share of the

global market in consumer drones is over 90%.

“In the area of

clean energy… the gains of Chinese companies are unambiguous. Whereas in 2015

they produced 65% of the world’s solar panels and 47% of its batteries, today

they are responsible for around 90% and 70%… In much of the world, the green

transition is powered by kit made in China.

“Chinese

manufacturers are making more stuff, but the government also wanted them to

make more innovative stuff. So the plan called on them to funnel 1.68% of their

total revenue into research and development by 2025, up from less than 1% in

2015. They achieved that objective in 2023. A related aim, for firms to file

more patents, has also been surpassed…

“China’s

manufacturing workforce was over 123m people in 2023. These labourers have

become more productive: output per worker has increased by roughly 6% a year on

average from 2014 to 2023.”2

In summary the

tariffs, sanctions etc introduce by the U.S, under Trump and Biden, while

causing some undoubted short-term problems, have strategically been a

failure—for reasons that will become clear.

International

economic problems and instability

If the facts

show clearly that China by a large margin outperformed the other major

economies in 2024 this, naturally, does not mean that China confronted no

problems. China’s December annual Central Economic Work Conference noted that

there had a been a problem earlier in 2024 of “insufficient domestic demand”.

The adjustment of China from being a medium level technology economy, strongly

powered by real estate, to a high-income economy, with advanced high-technology

manufacturing as its core, as is well known, will create problems of adjustment

as this transition is made. However, while real, these problems are small in

international comparative terms compared to the deep and intense

social/political instability which is clearly affecting the major Western

countries. The extremely striking nature of this was summarised by the fact

that of the seven leaders of the G7 countries that gathered for its annual

summit in June 2024 six have since been forced from office or suffered so far

unresolved governmental crisis.

- In the U.S. Biden was forced not to run for re-election and the governing Democrats lost both the ensuing Presidential and legislative elections.

- British Prime Minister Sunak was defeated at a general election.

- Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau was forced to resign.

- The German government led by Scholz government collapsed and his party faces certain defeat, probably by a landslide, in the February 2025 election.

- Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida was forced from office

- France’s president Macron lost the parliamentary elections and has been unable to form a stable government since.

In short, not

only were the other major economies economically outperformed by China but,

unlike China, they almost all showed very major political instability.

Explanation of

the differences in economic growth

Turning from

establishing the facts of 2024’s economic development to the explanation of

these international differences it will be seen that this also demonstrates

clearly what is required for China to achieve its strategic 2035 goals—as well

as the risks that could actually prevent this. This issue directly relates to

the discussion on the role of investment and consumption in the economy. This

issue is not in the sense of what may be required in short term stimulus

packages—for short term stimuluses boosting consumption may be needed—but in

what is strategically required for medium/long term growth and therefore for

meeting China’s goals to 2035.

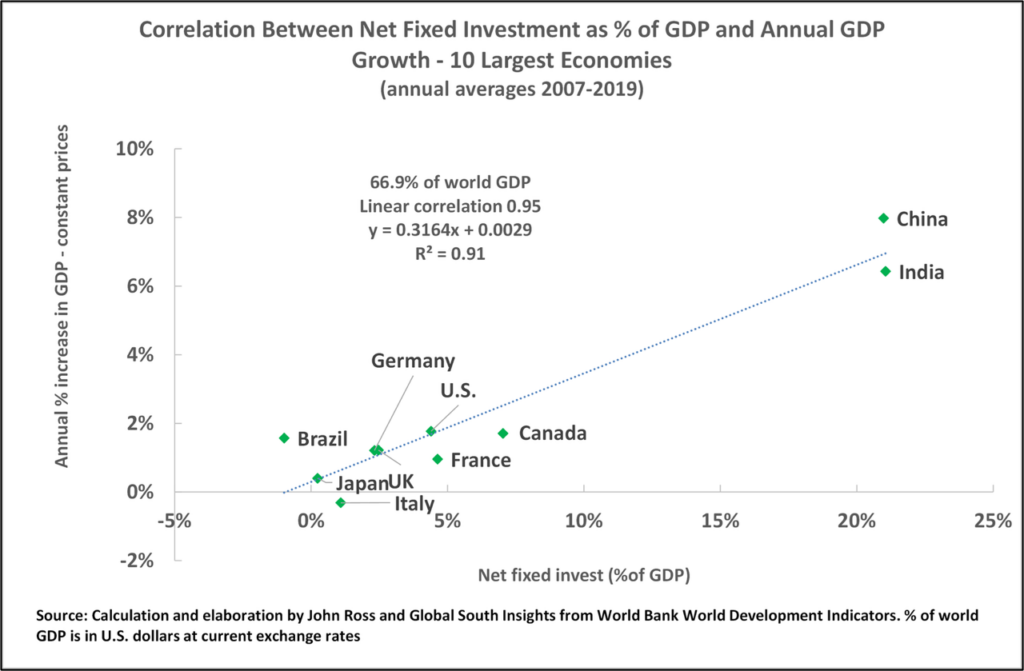

The decisive

issue in this is that the facts establish beyond doubt that in large economies

an overwhelmingly close positive correlation exists between the percentage of

net fixed capital formation in GDP and annual GDP growth (net fixed capital

formation is new fixed investment minus depreciation of existing capital, that

is it is the additional capital available to expand the economy). To see how

strong this relation is Figure 4 shows the development of the world’s 10

largest economies over the entire last international business cycle of

2007-2019. The whole business cycle is taken so as to remove the effect of

short-term business cycle fluctuations (although it should be noted that

extending the figures to the latest available data makes no essential difference

to the correlations despite the fluctuations created by Covid). For the world’s

10 largest economies, including China and the U.S., this positive correlation

between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and annual GDP growth is

0.95—as close to a perfect correlation as will be found in any practical

example.

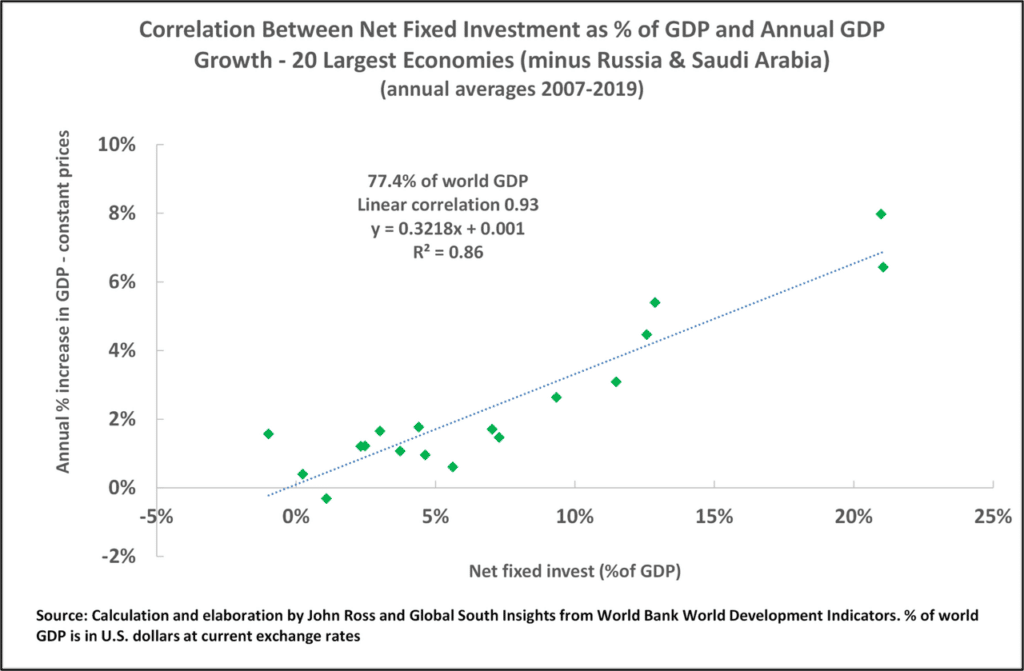

Taking the 20

largest economies in the world, excluding oil and gas export dominated

economies, which have a quite different pattern of development to other large

economies, then the correlation between net fixed capital investment and annual

GDP growth is also an ultra-high 0.93—see Figure 5.

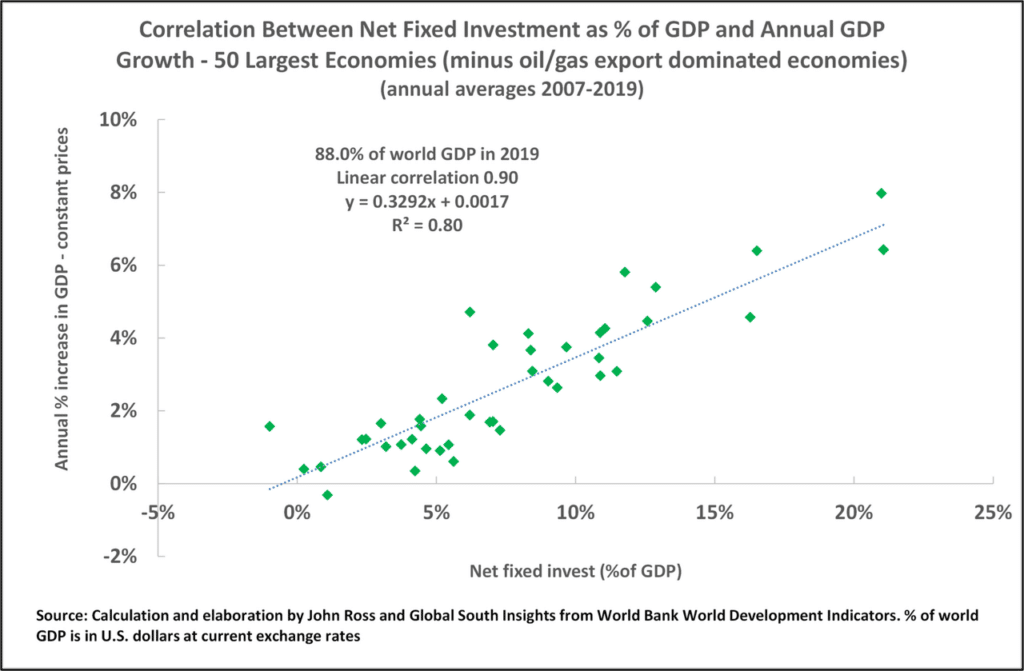

Even taking the

50 largest economies in the world, excluding oil and gas exporters, comprising

an overwhelming 88.0% of global GDP, the correlation remains an ultra-high

0.90.

China

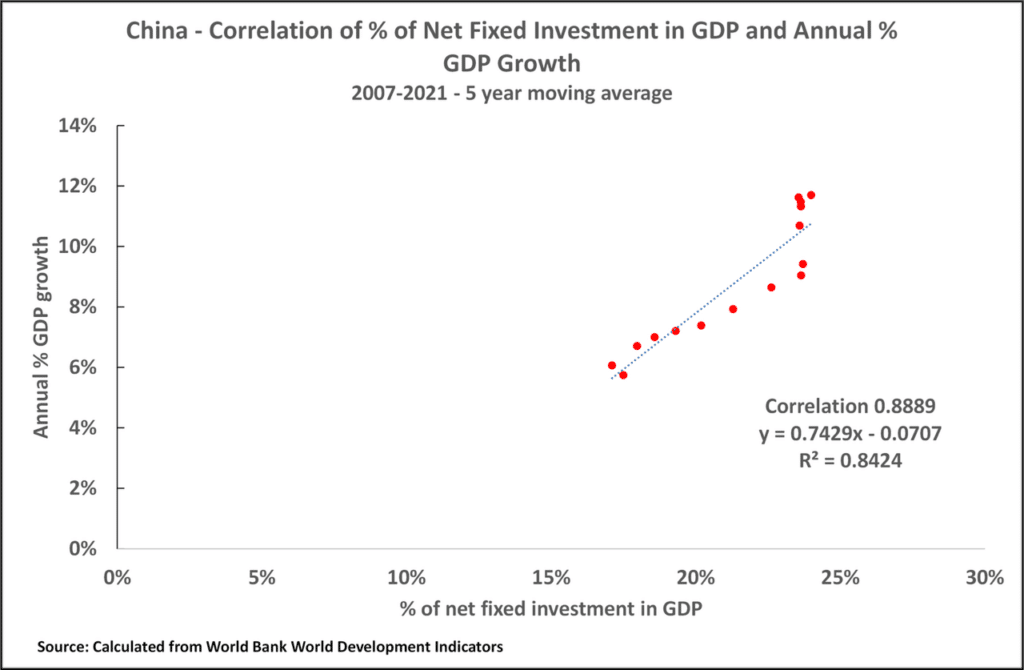

Considering the

development of China’s economy over time, taking the entire period since the

international financial crisis up to the latest available data for net fixed

capital formation, for 2021, then the correlation between the percentage of net

fixed investment in GDP and annual GDP growth, taking a five year moving

average to remove the effect of purely short term business cycle effects, is

entirely in line with these international facts, at an extremely high 0.89—see

Figure 7.

The role of

investment and consumption in the economy

The practical

consequences of such facts for economic development and policy are

overwhelming. It is not even necessary, for present purposes, to establish the

causal connection between the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and GDP

growth. This extremely close correlation simply means that it is impossible to

increase the rate of GDP growth without increasing the percentage of net fixed

investment in GDP. Equally reducing the percentage of net fixed investment in

GDP will necessarily reduce the rate of GDP growth. These relations are so

close that there is no way to avoid them.

The theoretical

explanation of these factual relations is also clear and directly relates to

the discussion on consumption and investment. Consumption and investment

together make up 100% of domestic GDP. Any increase in the percentage of

consumption in GDP therefore means a decline in the percentage of investment in

GDP and therefore a fall in the GDP growth rate.3

The reason for

this in economic theory is entirely clear. Consumption, by definition, is not

an input into production—if anything is an input into production it is not

consumption. Increasing the percentage of consumption in GDP therefore, other

things remaining equal, necessarily reduces the percentage of investment in

GDP, consequently the inputs into production and therefore GDP growth. In its

knock on consequences it also reduces the growth rate of consumption (For a

detailed factual and quantitative analysis of these relations please see 从210个经济体大数据中,我们发现了误解促消费对经济的危害.)

Put in technical

terms, consumption is not an input into the production function—either in terms

of Western or of Marxist economics. In Western economics the inputs into

production are capital, labour and total factor productivity (TFP) while in

Marxist terms they are dead labour (investment) and living labour—both of the

latter measured in terms of socially necessary labour time. In neither economic

system, nor any economic system whatever, is consumption an input into

production. That is, consumption is a part of the demand side of the economy,

it is not a part of the production, that is the supply side, of the economy.

Therefore, the

contribution of consumption to increases in production, and to GDP growth, is

always, in every year, precisely zero. Consequently, it follows that an

increase in the proportion of net investment in the economy increases GDP

growth while an increase in the percentage of consumption in the economy

reduces GDP growth—which in its knock on consequences, in reducing GDP growth,

means that an increase in the percentage of consumption in GDP will reduce the

growth rate of consumption.

The percentage

of consumption in GDP and the growth rate of consumption are negatively

related—the higher the percentage of consumption in GDP the slower will be the

growth rate of consumption and living standards. This point, which follows from

economic theory, is entirely confirmed by the facts. Again, for the details for

all countries please see 从210个经济体大数据中,我们发现了误解促消费对经济的危害.

Decline in net

fixed capital formation

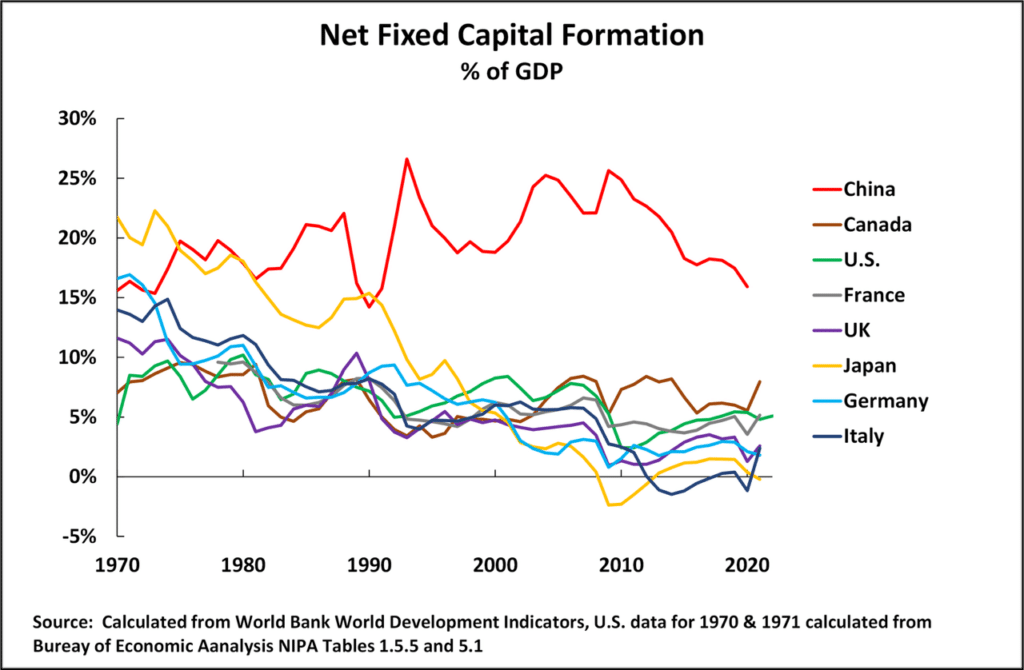

Given these

correlations Figure 8, which shows the percentage of net fixed capital

formation in GDP up to the latest available data for the major economies, makes

clear the reasons which explain the differences in international growth already

given—and the reasons for China’s outperformance in economic growth. As no data

is available for net fixed capital formation for the EU as a whole therefore

the data for the G7 economies and China is used in Figure 8— this includes the

four largest West European economies of Germany, France, UK and Italy.

As may be seen,

since 1970, up to the latest available data, for 2021, the percentage of net

fixed capital formation in the G7 economies, with the exception of Canada, has

fallen sharply.

- In the U.S. the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP fell from 8.5% to 5.1%.

- In Japan the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP fell from 21.7% to -0.2%.

- In Germany the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP fell from 16.6% to 1.8%.

- In the UK the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP fell from 11.6% to 2.6%.

- In Italy the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP fell from 14.0% to 2.4%.

- In France, data is available only from 1972, but from then until 2021 the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP fell from 9.6% to 5.2%.

- In Canada the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP rose slightly from 7.0% to 7.9% but remained in 2021 far below China’s level of 15.8% of GDP.

In 1970 China’s

level of net fixed capital formation in GDP, at 15.6%,was lower than Japan or

Germany, two economies which were growing rapidly at that time. By 2021 China’s

level of net fixed capital formation, was 15.8% of GDP—which was far higher

than any G7 economy. Given the extremely close correlation between the

percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and annual GDP growth the reason why

China’s economy was growing much faster than any of the G7 is clear.

How the U.S.

seeks to slow China’s economy

Given this

factual data, and the correlations involved, the decisive issue for China to

achieve its 2035 goals is evident—as is also what the U.S. would have to

accomplish to slow China’s economy. It follows clearly from these facts that In

order to maintain a growth rate high enough to achieve its 2035 goals China has

to maintain a high level of net fixed investment. Equally, to slow China, the

U.S. has to find a way cut China’s level of net fixed capital investment in

GDP. This cutting of the proportion of investment in GDP was the method by

which, in earlier periods, the U.S. successfully drastically slowed its

competitor economies of Germany, Japan, South Korea and the other Asian

Tigers—for the details of the U.S. tactics to achieve this see “The U.S. is

trying to persuade China to commit suicide”.

But the U.S. was

able to force Japan, Germany and the Asian Tigers to cut the proportion of

investment in GDP because they were militarily and economically subordinate to

the U.S. That is, the U.S. was able to use this leverage and power to “murder”

these competitors. But China is not militarily and economically subordinate to

the U.S., therefore the U.S. cannot use the same tactics against China.

Furthermore, the

factual data already given shows clearly that the U.S. policy of tariffs and

economic sanctions against China since 2018 has not succeeded in significantly

reducing China’s level of investment in GDP. Data for 2022 and 2023, allowing

net fixed capital formation to be calculated, is not available from the World

Bank, but data for gross fixed investment, that is before taking into account

depreciation, is available. This shows that in 2017, before the introduction of

the tariffs and sanctions by Trump, China’s gross fixed capital formation was

41.9% of GDP and in 2023 it was 41.3%. This is a totally marginal decline.

There is a longer-term issue, in that the level of depreciation in an economy

increases with time and the consequences of this will be analysed in a future

article. But for the present, and in the immediate future, if China’s level of

gross fixed capital formation does not fall then it can continue to achieve the

growth rates necessary to achieve its 2035 strategic goals.

What is the U.S.

attempting to use to reduce China’s level of investment

But if the U.S.

has no military control over China which can enable it to force China to reduce

its level of investment, and the U.S. sanctions and tariffs are not powerful

enough to achieve this, that is the U.S. has no way to “murder” China, then the

U.S. has only one economic possibility—that is to attempt to persuade China to

commit economic “suicide”. The instrument for doing this is confused

anti-Marxist economic ideas.

Xi Jinping has

stated that: “our study of political economy must be based on Marxist political

economy and not any other economic theory.”1 Marx demonstrated that it was

production, that is the process of creating goods and services, which would be

consumed, that was the determining factor in the economy. As Marx noted: ‘The

result at which we arrive is, not that production, distribution, exchange and

consumption are identical, but that they are all elements of a totality,

differences within a unity. Production is the dominant moment, both with regard

to itself in the contradictory determination of production and with regard to

the other moments. The process always starts afresh with production… exchange

and consumption cannot be the dominant moments… A definite [mode of] production

thus determines a definite [mode of] consumption, distribution, exchange.’2

This analysis, of course, directly predicts to the factual correlations noted

above in which investment, one of the key elements in production, determines

both GDP growth and consumption growth.

As the U.S. has

no way to compel China to reduce its level of investment, no way to “murder”

China, the U.S. is instead forced to rely on giving its support to views

advocating a radical increase in the share of consumption in the economy in

order to get China to commit economic suicide. This is therefore supported by a

stream of propaganda for this in media publicised by the U.S..

Self-confidence

These economic

facts, in turn, intertwine with broader issues. In its attempt to economically

derail China one of the most bizarre arguments used by the U.S. relies on

Western arrogance. This argument takes the form of accurately noting that

China’s economy is different to a Western economy in that it has a much higher

level of investment. A typical example is in a recent study by Goldman Sachs.

This difference of China to the West is, of course, entirely accurate. Because

if China had the same economic structure as a Western economy, then it would be

growing at the much slower pace of a Western economy instead of 80% faster than

the U.S. and more that four times as fast as Europe!

From the fact

that China’s economy is growing much faster than a Western economy the obvious

logical conclusion which should be drawn by any objective analyst is that the

Western economies therefore need to adjust their structure more towards that of

China. Instead, the completely bizarre conclusion is suggested that because

China’s economy is growing much faster than the Western economies therefore

China should change its economic structure to that of the much less rapidly

growing Western economies! The only reason such an evidently totally illogical

conclusion can be put forward is because of an assumption that it must be the

West which is correct.

To make a

comparison, suppose Goldman Sachs were approached for advice by a company

wishing to enter a new industry. And Goldman Sachs said: “We have studied the

industry and note that one company is growing much more rapidly than its

competitors. So, you must not learn from, or adopt the methods, of this most

rapidly growing successful economy. You should instead follow the approach and

methods of the less successful companies. Meanwhile we have contacted the most

rapidly growing company and advised it that it should copy its less successful

competitors so that it can slow itself down to their growth rate.” Everyone

would laugh at such advice… just before they cancelled their contract with

Goldman Sachs! But that is exactly what those who advise China to move towards

the model of a Western economy propose!

It is indeed

cultural Western arrogance that prevents any person seeing the absurdity of

drawing the conclusion from the different levels of investment in a Western

economy and China that it is China that should change itself to slower growing

Western model rather than that the Western economies should move closer to the

more rapidly growing economy of China.

Conclusion

It is necessary

to be completely clear that it is impossible to avoid the facts regarding the

correlation of investment and economic growth that were set out towards the

beginning of this article. In the famous and profoundly true saying of China it

is precisely necessary in economic development to follow the method to “seek

truth from facts”. This expresses in a succinct way a reality also pointed out

in other languages—for example one of the U.S.’s founding fathers, its second

President John Adams, rightly and similarly : “Facts are stubborn things; and

whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions,

they cannot alter the state of facts.”

This exactly

applies to the relation of investment and economic growth. The factual

relations stated towards the beginning of this article are inescapable—no

appeals to false theories, such as those of “vulgar” Western economics, or

Western arrogance, will alter them. They inevitably mean that if China

maintains a high level of investment in GDP it can achieve its 2035 goals. If

China could be persuaded by U.S. propaganda to cut its levels of investment in

GDP, to move closer to a Western model, it would fail to achieve its strategic

2035 goals.

During the

century of humiliation China was largely controlled by external forces. But due

to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, China now controls its

own fate. As a result of these immense achievements today the most important

decisions in the world are taken in China—that is not a statement of arrogance,

or politeness to China from a foreigner, it is simply a statement of objective

fact.

China, of

course, develops in entirely specific national conditions. As Deng Xiaoping

stated, in establishing China’s Reform and Opening Up: ‘To accomplish

modernization of a Chinese type, we must proceed from China’s special

characteristics,’3 and China must ‘blaze a path of our own.’4 But these

entirely specific national conditions do not mean that China can escape from

the facts and from laws of economics—it simply means that these facts and laws

combine in a completely specific way in China. As Deng Xiaoping put it: ‘We

have tried to act in accordance with objective economic laws.’5

The facts of

economic development regarding the relation of investment and economic growth

were set out at the beginning of this article. These facts determine that if

China continues to act in accord with them, as it has done so far, then it will

achieve its goals to 2035 and achieve an enormous further step forward in its

national rejuvenation. This, because China’s national rejuvenation is the most

important process taking place in the world today, will have consequences far

outside China.

It means that

the realm of economic ideas has become a key part of China’s national

rejuvenation. This is because as Jinping has stated: “The path of Chinese

socialism… takes economic development as the central task, and brings along

economic, political, cultural, social, ecological and other forms of

progress.”6

Acknowledgement

The analysis of

the correlation of the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP and the annual

rate of GDP growth is from work carried out jointly with Global South Insights.

[i] Speech at

the 28th group study session of the Political Bureau of the 18th CPC Central

Committee on November 23, 2015

[ii] Karl Marx,

Economic Manuscripts of 1857-61 (Vol. Collected Works 28). London: Lawrence and

Wishart p36.

[iii] (Deng X. ,

30 March 1979)

[iv] (Deng X. ,

21 August 1985)

[v] (Deng X. ,

30 March 1979, p. 173)

[vi] (Xi, Study,

Disseminate and Implement the Guiding Principles of the 18th CPC National

Congress, 2014, p. Location 219)

Bibliography

- Deng, X. (21 August 1985). Two Kinds of Comments About China’s Reform. In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping Vol. 3 1982-1992 (1994 ed., pp. 138-9). Foreign Languages Press.

- Deng, X. (30 March 1979). Uphold the Four Cardinal Principles. In 2001 (Ed.), Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping 1975-1982 (pp. 166-191). Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific.

- Marx, K. (1857). Economic Manuscripts of 1857-1861 (Vol. Collected Works 28). Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- The Economist. (2025, January 18). The consequences of success. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/china/2025/01/16/an-initiative-so-feared-that-china-has-stopped-saying-its-name

- Xi, J. (2012 November 17). Study, Disseminate and Implement the Guiding Principles of the 18th CPC National Congress. In J. Xi, The Governance of China (Kindle Edition) (2014 ed., Vol. 1, pp. Location 165-449). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

- Xi, J. (2020, November 03). Explanation of the CPC Central Committee’s Proposal on Formulating the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Term Goals for 2035. Retrieved from Xinhuanet: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2020-11/03/c_1126693341.htm?mc_cid=afeb03209b&mc_eid=c8292ef9bf

Notes:

- ↩ As outlined by Xi Jinping: “regarding the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ and the economic development goals by 2035. During the consultation process, some localities and departments suggested clearly proposing the economic growth rate goal of the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ and clearly proposing the goal of doubling the economic aggregate or per capita income by 2035. After careful research and calculations, the document drafting team believes that from the perspective of economic development capabilities and conditions, my country’s economy has the hope and potential to maintain long-term stable development, reach the current high-income country standards by the end of the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’, and achieve economic growth by 2035. It is entirely possible to double the total or per capita income.” (Xi Jinping: Explanation on the “Recommendations of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Formulating the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-term Goals for 2035” http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2020-11/03/c_1126693341.htm?mc_cid=afeb03209b&mc_eid=c8292ef9bf

- ↩ The Economist. (2025, January 18). The consequences of success. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/china/2025/01/16/an-initiative-so-feared-that-china-has-stopped-saying-its-name

- ↩ Strictly speaking, as investment constitutes both fixed investment and accumulation of inventories, a change in inventories needs to be taken into account. However, in practice, accumulation of inventories is much too small a proportion of GDP to affect the fundamental situation, which is determined by the far larger items of consumption and fixed investment.

- ↩ Speech at the 28th group study session of the Political Bureau of the 18th CPC Central Committee on November 23, 2015

- ↩ Karl Marx, Economic Manuscripts of 1857-61 (Vol. Collected Works 28). London: Lawrence and Wishart p36.

- ↩ (Deng X. , 30 March 1979)

- ↩ (Deng X. , 21 August 1985)

- ↩ (Deng X. , 30 March 1979, p. 173)

- ↩ (Xi, Study, Disseminate and Implement the Guiding Principles of the 18th CPC National Congress, 2014, p. Location 219)

No comments:

Post a Comment