September

12, 2023

India

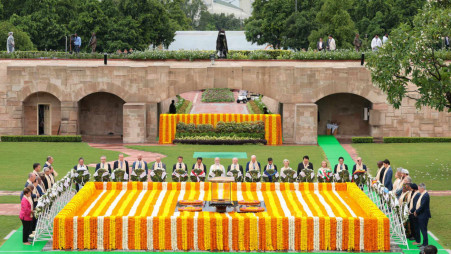

being the host country, the triumphalist tom-toming that G20 summit on

September 9-10 was a “success” is both understandable and probably justifiable.

Certainly, Indian diplomacy was in full cry. The negotiation of the G20

Declaration is no mean achievement in a highly polarised environment.

That

said, in a forward-looking perspective, the geopolitical factors that were at

work in the Delhi summit will continue to remain the critical determinants for

the G20’s future as a format to forge new directions in economic strategies. In

a world torn apart, many imponderables remain.

The

geopolitical factors can be attributed largely to the fact that the G20 summit

took place at an inflection point in the Ukraine war, an event that is, like

the tip of an iceberg, a manifestation of the tensions building up between the

Western powers and Russia in the post-cold war era.

The

heart of the matter is that the Cold War ended through negotiations but the new

era was not anchored in any peace treaty. The void created drift and anomalies

— and security being indivisible, tensions began appearing as the NATO embarked

on an expansion eastward into the former Warsaw Pact territories in the late

1990s.

With

great prescience, George Kennan, the choreographer of Cold War strategies,

forewarned that the Bill Clinton administration, seized of the “unipolar

moment,” was making a grave mistake, as Russia would feel threatened by NATO

expansion, which would inexorably complicate the West’s relations with Russia

for a long, long time to come.

But

NATO kept expanding and slouching toward Russia’s western borders in an arc of

encirclement. It was an unspoken secret that Ukraine was set to become

ultimately the battleground where the titanic forces would clash.

Predictably,

following the regime change in Ukraine backed by the West in 2014, an

anti-Russian regime was installed in Kiev and the NATO embarked on a military

build-up in that country alongside a concerted plan to induct it into the

western alliance system.

Suffice

to say, the “consensus” evolved at the G20 summit last week regarding Ukraine

war is, in reality, a passing moment in the geopolitical struggle between the

US and Russia, as embedded within it is the

existential crisis Russia faces.

There

is no shred of evidence that the US is willing to concede the legitimacy of

Russia’s defence and security interests or to give up its notions of

exceptionalism and world hegemony. If anything, a very turbulent period lies

ahead. Therefore, do not exaggerate the happy tidings out of the Delhi summit,

much as one may savour the moment.

Washington’s

climbdown at the summit regarding Ukraine has been both a creative response to

the mediatory efforts by the three BRICS countries — South Africa, India and

Brazil — as much as, if not more, in its self-interest to avert isolation from

the Global South.

Evidently,

while Moscow is profusely complimenting India and Modi, the opposite is the

case in the western opinion where the compromise on Ukraine has not gone down

well at all. The British newspaper Financial Times, which is wired into

government thinking, has written that Delhi Declaration refers only to the “war

in Ukraine,” a formulation that supporters of Kiev such as the US and NATO

allies have previously rejected, as it implies both sides are equally

complicit, and “called for a ‘just and durable peace in Ukraine’ but did not

explicitly link that demand to the importance of Ukraine’s territorial

integrity.”

Indeed,

feelings are running high and, no doubt, as the Ukraine war enters the next

brutal phase, they will boil over at the prospect of a Russian victory.

Again,

there is no question that the West feels challenged by the dramatic surge of

BRICS — more to the point, the group’s seductive appeal among the developing

countries, the so-called Global South, unnerves the West.

The

West can never hope to gain entry into the BRICS tent, either. Meanwhile, the

BRICS is moving with determination in the direction of replacing the

international trading system which provided underpinning for western hegemony.

The US’ weaponisation of sanctions — and the seizure of Russian reserves

arbitrarily — has created misgivings in the minds of many nations.

Plainly

put, the US has forgotten its solemn promise when dollar replaced gold as the

reserves in the early 1970s that its currency will be freely accessible for all

countries. Today, the US turned that promise upside down and exploits dollar’s

primacy to print the currency as much as it wants and live beyond its means.

The

growing trend is toward trading in local currencies, bypassing dollar. The

BRICS is expected to accelerate these shifts. Make no mistake, sooner or later,

BRICS may work on an alternative currency to replace dollar.

Conceivably,

therefore, there will be western conspiracies to create dissonance within

BRICS, and Washington is sure to continue to play on India’s disquiet over

China’s towering presence in the Global South. While exploiting Indian phobias

regarding China, the Biden administration also looks toward Modi government to

act as a bridge between the West and the Global South. Are such expectations

realistic?

The

current developments in Africa with a pronounced anti-colonial, anti-western

overtone, directly threaten to disrupt the continued transfer of wealth out of

that resource-rich continent to the West. How can India, which has known the

cruelty of colonial subjugation, collaborate with the West in such a paradigm?

Fundamentally,

all these geopolitical factors taken into account, G20’s future lies in its

capacity for internal reform. Conceived during the financial crisis in 2007

when globalisation was still in vogue, G20 is today barely surviving in a

vastly different global environment. Added to that, the “politicisation”

(“Ukrainisation”) of G20 by the Western powers undermines the format’s raison

d’être.

The

world order itself is in transition and the G20 needs to move with the times to

avoid obsolescence. For a start, the G20 format is packed with rich countries,

most of whom are pretenders with little to contribute, at a juncture when the

G7 no longer calls the shots. In GDP terms or population, BRICS has overtaken

G7.

Greater

representation of the Global South is needed by replacing the pretenders from

the industrial world. Second, the IMF needs urgent reform, which is of course

easier said than done, as it involves the US agreeing to give up its undue

privileges of vetoing decisions it disfavours for political or geopolitical

reasons — or, plainly, to punish certain countries.

With

IMF reform, the G20 can hope to play a meaningful role focused on creating a

new trading system. But the West is playing for time by politicising the G20,

paranoid that its 5-centuries old dominance of the world economic order is

ending. Unfortunately, visionary leadership is conspicuous by its absence in

the Western world at such a historic moment of transition.

As

far as India is concerned, the main challenge is two-fold: commitment to the

uplift of the Global South by making it a central plank in its foreign-policy

priorities and secondly, perseverance in follow-up of what it espoused during

the G20 summit deliberations.

Herein

lies the danger. In all probability, with the G20 Leaders gone from Indian

soil, Delhi may revert to its China-centric foreign policies. India’s

commitment to the cause of the Global South should not be episodic. Delhi is

wrong to assume it is a Pied Piper.

Such

a mindset may work in Indian politics — for sometime at least — but the Global

South will see through our mindset and conclude that India is only helping

itself in its frenzy to carve out a place for itself at the high table of world

politics.

Put

differently, Modi government must ask itself not what the Global South can do

for boosting India’s international standing but, genuinely, what it can do for

the Global South.

No comments:

Post a Comment