November

9, 2023

How a dogged journalist proved that the CIA lied about Oswald

and Cuba — and spent decades covering it up.

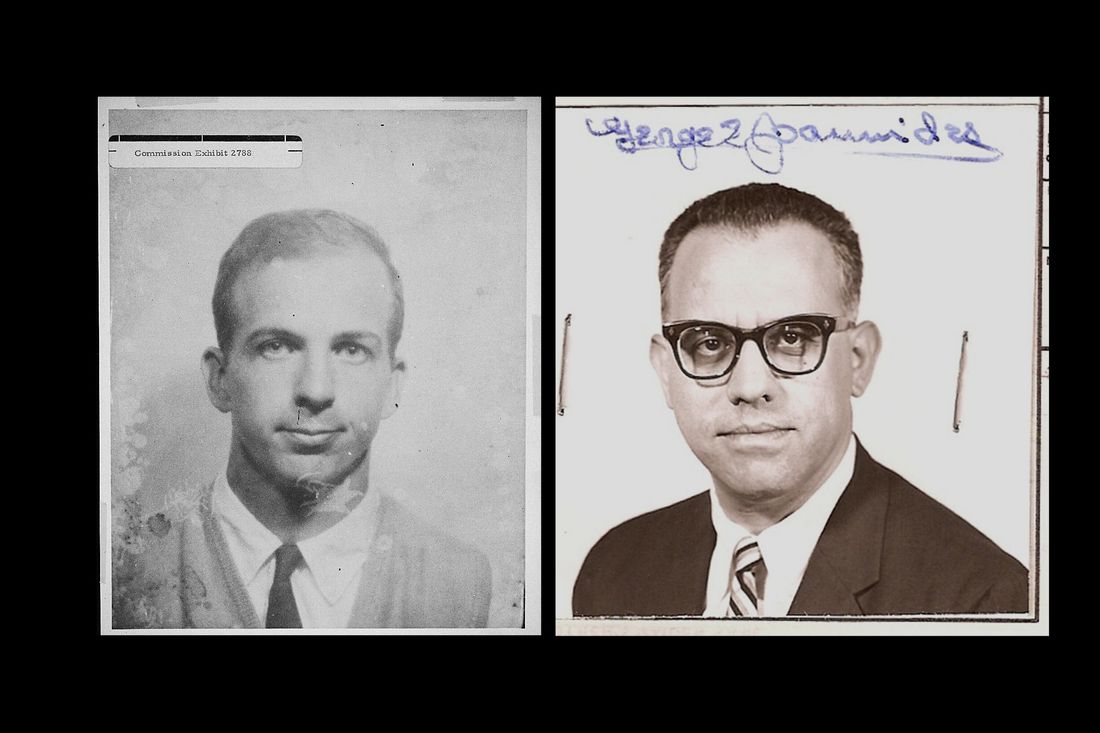

Lee Harvey Oswald and CIA officer George Joannides.

Photo: JFK Assassination Records Collection (Oswald) & CIA FOIA files (Joannides

In

1988, in an elevator at a film festival in Havana, the director Oliver Stone

was handed a copy of On the Trail of the Assassins, a newly published account

of the murder of President John F. Kennedy. Stone admired Kennedy with an

almost spiritual intensity and viewed his death on November 22, 1963 — 60 years

ago this month — as a hard line in American history: the “before” hopeful and

good; the “after” catastrophic. Yet he had never given much thought to the

particulars of the assassination. “I believed that Lee Oswald shot the

president,” he said. “I had no problem with that.” On the Trail of the

Assassins, written by the Louisiana appellate judge Jim Garrison, proposed

something darker. In 1963, Garrison had been district attorney of New Orleans,

Oswald’s home in the months before the killing. He began an investigation and

had soon traced the contours of a vast government conspiracy orchestrated by

the CIA; Oswald was the “patsy” he famously claimed to be. Stone read

Garrison’s book three times, bought the film rights, and took them to Warner

Bros. “I was hot at the time,” Stone told me. “I could write my own ticket,

within reason.” The studio gave him $40 million to make a movie.

The

resulting film, JFK, was a scandal well before it came anywhere near a theater.

“Some insults to intelligence and decency rise (sink?) far enough to warrant

objection,” the Chicago Tribune columnist Jon Margolis wrote just as shooting

began. “Such an insult now looms. It is JFK.” Newsweek called the film “a work

of propaganda,” as did Jack Valenti, the head of the Motion Picture Association

of America, who specifically likened Stone to the Nazi filmmaker Leni

Riefenstahl. “It could spoil a generation of American politics,” Senator Daniel

Patrick Moynihan wrote in the Washington Post.

Critics

objected in particular to Stone’s ennoblement of Garrison, whose investigation

was widely viewed, including by many conspiracy theorists, as a farce. And yet

some of the response to the film looked an awful lot like a form of repression,

a slightly desperate refusal to acknowledge that the official version of the

Kennedy assassination had never been especially convincing. One week after the

assassination and five days after Oswald himself was killed by nightclub owner

Jack Ruby, President Lyndon Johnson convened a panel of seven “very

distinguished citizens,” led by Chief Justice Earl Warren of the Supreme Court,

to investigate. Ten months later, the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald,

firing three shots from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository,

had killed Kennedy entirely on his own for reasons impossible to state.

Notwithstanding JFK’s distortions — “It’s a Hollywood movie,” Stone pointed out

— the film noted quite accurately that the Warren Commission seemed to be

contradicted by its own evidence.

In

a famous courtroom scene, Garrison, played by Kevin Costner, showed the

Zapruder film, the long-suppressed footage of the shooting, rewinding it for

the jury as he narrated the movement of Kennedy’s exploding cranium — “Back,

and to the left; back, and to the left” — which suggested a shot not from

behind, where Oswald was, but from the front right, in the direction of the

so-called Grassy Knoll, where numerous witnesses testified to having seen,

heard, and even smelled gunshots. (Stone had offered the role of Garrison to

Harrison Ford and Mel Gibson, who both passed, but Costner, the very symbol of

wholesome Americana, was actually the more subversive choice.) In another

courtroom scene, Garrison appeared to dismantle the “single-bullet theory,”

according to which the same round had been responsible for seven entry and exit

wounds in Kennedy and Texas governor John Connally — an improbable scenario

made all the more so by the alleged bullet itself, which was recovered in

near-pristine condition. The simplest explanation would have been that all

those wounds were caused by more than one bullet, but this would have meant

either that Oswald had fired, reloaded, and again fired his bolt-action rifle

in less than the 2.3 seconds required to do so or, more realistically, that

there was a second shooter.

Three

of the seven members of the Warren Commission eventually disavowed its

findings, as did President Johnson. In 1979, after a thoroughgoing

reinvestigation, the House Select Committee on Assassinations officially

concluded that Kennedy “was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.”

But such findings seemed not to penetrate. “In view of the overwhelming

evidence that Oswald could not have acted alone (if he acted at all), the most

remarkable feature of the assassination is not the abundance of conspiracy

theories,” Christopher Lasch, the historian and social critic, remarked in

Harper’s, “but the rejection of a conspiracy theory by the ‘best and

brightest.’” For complex reasons of history, psychology, and politics, within

the American Establishment it remained inadvisable to speak of conspiracy

unless you did not mind being labeled a kook.

Stone

ended his film in the style of a documentary, with a written text scrolling

beneath John Williams’s high-patriotic arrangement for string and horns, that

deplored the official secrecy that still surrounded the assassination. Large

portions of the Warren Report, Kennedy’s full autopsy records, and much of the

evidence collected by the HSCA had never been cleared for public release. When

JFK came out in December 1991, this ongoing secrecy quickly supplanted the

movie itself as a subject of public scandal. Within a month, the New York Times

was editorializing, if begrudgingly, in Stone’s defense. (“The public’s right

to information does not depend on the integrity or good faith of those who seek

it.”) By May 1992, congressional hearings about a declassification bill were

underway. Stone, invited to testify before the House, declared, “The stone wall

must come down.” CIA director Robert Gates pledged to disclose, or at least

submit for review, “every relevant scrap of paper in CIA’s possession.” “The only

thing more horrifying to me than the assassination itself,” Gates said, “is the

insidious, perverse notion that elements of the American government, that my

own agency had some part in it.”

The

President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992 mandated

that “all Government records related to the assassination” be provided to the

National Archives and made available to the public. The historian Steven M.

Gillon has called it the “most ambitious declassification effort in American

history.” It has done little to refute Gates’s “insidious, perverse notion.” On

the contrary, for those with the inclination to look and the expertise to

interpret what they find, the records now in the public realm are terrifically

damning to the Warren Commission and to the CIA.

Among

the first visitors to the JFK Assassination Records Collection was Jefferson

Morley, then a 34-year-old editor from the Washington Post. Morley had made a

name for himself in magazines in the 1980s. He helped break the Iran-Contra

scandal for The New Republic and wrote a much-discussed gonzo essay about the

War on Drugs for which he’d spent an evening smoking crack cocaine. By that

time, he’d become Washington editor of The Nation. He drank with Christopher

Hitchens, with whom he was once deported, after a gathering with some Czech

dissidents, by that country’s secret police. “He was a little out there,” a

colleague at the Post recalled. “But you want some people like that in the

newsroom.” Morley had read about the Kennedy assassination for years as a

hobby, but it never occurred to him that he might report on it himself. “I

never thought I had anything to add,” he told me. “Until 1992.”

I

visited Morley in Washington in September. He is now 65 and somewhat more

demure than his younger self, if still combative, with a sweep of gray hair, a

high brow, and a sharp nose that together lend him a vaguely avian aspect, an

impression heightened by his tendency to cock his head quizzically, like an

owl, and speak into the middle distance. We met at the brick rowhouse that he

still shares with his second wife, with whom he is in the midst of a divorce.

She will keep the house, and Morley was not yet certain where he would go, but

they agreed that he could stay through “the coming JFK season,” as he put it.

His small office is there, as is his personal file collection, three decades of

once-classified records culled from the National Archives and stored in worn

banker’s boxes, tens of thousands of photocopy sheets arranged chronologically

and, in duplicate form, by subject matter. “If you use what we’ve learned since

the ’90s to evaluate the government’s case,” he told me, “the government’s case

disintegrates.”

Morley,

the author of three books on the CIA and the editor of a Substack blog of

modest but impassioned following called JFK Facts, has made a name for himself

among assassination researchers by attempting to approach Kennedy’s murder as

if it were any other subject. “Journalists never report the JFK story

journalistically,” he said. Early on, when Morley was still at the Post,

editors would frequently ask, “What does this tell us about who shot JFK?” “I

have no idea!” he responded. “I have to have a fucking conspiracy theory?”

He

did not set out to make a career of the JFK Act, but the declassification

process has taken longer than expected. At the urging of the CIA and other

agencies, President Donald Trump twice extended the original 2017 deadline. In

2021, President Joe Biden pushed it to 2022 before extending it once again. At

least 320,000 “assassination-related” documents have been released; by one

estimate, some 4,000 remain withheld or redacted, the majority belonging to the

CIA.

Morley’s

serious interest in the assassination had begun in the early 1980s, prompted by

Christopher Lasch’s attack on the conspiracy taboo in Harper’s. (He’d helped

edit the essay.) He began to read the available literature. Some of the

“conspiracy” books were highly suppositious, in his view, but some he found to

be impressively thoughtful, documented, even restrained. Sylvia Meagher’s 1967

critique of the Warren Commission, Accessories After the Fact, based on a close

reading of the commission’s report and its appendices, was particularly

influential. The report “didn’t hang together,” Morley said, “didn’t make sense

on its own terms.”

In

1992, during passage of the JFK Act, he was hired by the Washington Post to

work for “Outlook,” the paper’s Sunday opinion section, an outpost of

impertinence and boundary-testing in an otherwise buttoned-down newsroom. By

Morley’s recollection, he pitched a piece about the JFK archive during his job

interview. “They didn’t realize all these records were coming out, they weren’t

really paying attention, and I was on the ball,” Morley said.

Morley

visited the new archive after work, prospecting for stories, and began

contacting researchers of the assassination to ask for guidance. Among them was

John Newman, a U.S. Army major who had spent 20 years in Army intelligence and

written a widely praised history of Kennedy and Vietnam. Newman, who also

served as a consultant on JFK, was then at work on a book about Oswald and his

connections to the CIA.

The

possibility of such a tie had been floated since almost the moment Kennedy was

shot. The mutual detestation between Kennedy and the Agency, especially after

the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion, was widely known in Washington. It is a

measure of the paranoia of the era, and also of the Agency’s reputation for

lawlessness, that on the afternoon of his brother’s murder, Robert Kennedy

summoned the director of the CIA to his home to ask “if they” — the CIA — “had

killed my brother,” Kennedy later recalled. (The director, John McCone, said

they had not.) The Agency assured the Warren Commission that, prior to the

assassination, it had had no particular interest in Oswald and almost no

information on him whatsoever. This had always seemed implausible. Oswald was

only 24 when he died, but his life had been eventful. He had served as a radar

operator in the Marine Corps, stationed at an air base in Japan from which the

CIA flew U-2 spy missions over Russia; had then defected to Moscow, where he

told American diplomats that he planned to tell the Soviets everything he knew;

had been closely watched, if not recruited, by Soviet intelligence services;

and had then, in 1962, after more than two and a half years in the USSR,

returned, Russian wife in tow, to the United States. One would think the CIA

might have taken somewhat more than a passing interest.

Early

on, Newman had photocopied the entirety of Oswald’s pre-assassination CIA file

at the archive and brought it home. Morley came often to study it. “I had read

something that said, you know, they only had five documents on him,” Morley

said. “And it was like, ‘No, there were 42.’”

Whatever

mystique may attach to it, the CIA is also a highly articulated bureaucracy.

Newman encouraged Morley to focus less on the documents themselves than on the

attached routing slips. “When you start getting into spy services, everybody

lies,” Newman told me. “And so how do you know anything?” The answer was

“traffic analysis.” Even if the information contained in an intelligence file

was false, Newman believed an account of how that information flowed — who

received it, in what form, from whom, when — could be a reliable source of

insight.

Via

cryptic acronyms, the Agency’s routing slips recorded precisely who had been

receiving information on Oswald in the period leading up to the assassination.

“It was, when you saw it, a lot of people,” Morley recalled. “I just remember

being in John’s basement and thinking, Oh my God.” A large number of senior CIA

officers at the Agency’s headquarters had evidently been tracking Oswald, and

tracking him closely, since well before November 22, 1963. “The idea that this

guy came out of nowhere was self-evidently not true,” Morley said. “That was a

door swinging open for me.”

Oswald’s

file contained press clippings, State Department archives, and FBI reports

detailing his activities in Fort Worth, Dallas, and New Orleans, where he’d

been arrested in the summer of 1963 and interviewed at length, in jail, by an

agent of the bureau. Of particular interest to Morley, however, was a series of

CIA cables from October 1963, the month before the assassination, pertaining to

a trip Oswald took to Mexico City.

By

the Warren Commission’s determination, Oswald arrived in Mexico City on

September 27. Before his return to the U.S. six days later, he seemed to have

made several visits to the embassies of both the Soviet Union and Cuba. But

there were problems with the evidence. The Warren Commission could not

definitively establish that the man who presented himself at the embassies as

Oswald was, in all instances, Oswald. A surveillance photograph of a man

outside the Soviet Embassy, purportedly of Oswald, was clearly not. This

“Mexico Mystery Man” has never been positively identified; no photographs of

Oswald in Mexico City have ever surfaced. A CIA wiretap had also picked up

someone presenting himself to the Soviets as “Lee Oswald,” but those who later

heard the recording, including FBI agents and staff lawyers for the Warren

Commission, reported that the caller was not him.

In

the file, Morley found a cable from the CIA’s Mexico City station to

headquarters in Langley reporting the phone call. “AMERICAN MALE WHO SPOKE

BROKEN RUSSIAN SAID HIS NAME LEE OSWALD,” it read. Headquarters responded in a

cable dated October 10, recounting Oswald’s defection and his time as a factory

worker in Minsk. But it seemed to indicate that the CIA had lost track of him.

“LATEST HDQS INFO” was a State Department report from May 1962 before Oswald

had returned to the U.S. from the Soviet Union, the cable said. Having seen the

CIA file, Morley knew this was not true: The CIA held extensive information on

Oswald’s activities in the U.S. from as recently as just a few weeks earlier,

including his arrest in New Orleans. Had CIA headquarters acted intentionally,

Morley wondered, when it misled the Agency’s people in Mexico City about the

man who six weeks later would be accused of killing the president?

He

and Newman checked the routing slips. The October 10 cable had received the

sign-off of several notably senior officials, including the No. 2 in the

Agency’s covert-operations branch. But of particular note was a lesser-known

signatory, Jane Roman, a top aide to James Jesus Angleton, the Agency’s famous

counterintelligence chief. Just days before approving the October 10 cable,

Roman had, in her own hand, signed for FBI reports that placed Oswald

unequivocally in the U.S.

Morley

and Newman found Roman’s address and visited her at her ivied bungalow in

Cleveland Park, a tony D.C. neighborhood favored by CIA officials. Roman, then

78, was reserved but cordial, “a correct, smart, Wasp woman,” Morley said. She

seated her visitors at a dining table beneath the dour portrait of a forebear.

Newman

asked most of the questions. (Newman and Morley are still friendly, but each

has a tendency to present himself as the central protagonist in the story of

Jane Roman. Roman died in 2007.) He spread documents on the table and walked

Roman through them, beginning with a routing slip from shortly after Oswald’s

return from the USSR. It had been signed by officials of the Soviet Realities

branch, of counterintelligence, of covert operations, and elsewhere. Newman

asked, “Is this the mark of a person’s file who’s dull and uninteresting?” “No,

we’re really trying to zero in on somebody here,” Roman said. Newman showed her

the FBI report on Oswald’s arrest in New Orleans, for which Roman had signed on

October 4, 1963. Newman then produced the October 10 cable, according to which

the Agency had received no information on Oswald in over a year.

“Jane,”

Newman said, “you read this file just a couple of days before you released this

message. So you knew that’s not true.”

Roman

protested that she had “a thousand of these things” to handle. But she soon

conceded, “Yeah, I mean, I’m signing off on something that I know isn’t true.”

Newman asked if this suggested “some sort of operational interest in Oswald’s

file.”

“Well,

to me, it’s indicative of a keen interest in Oswald, held very closely on the

need-to-know basis,” Roman said. She speculated that there had been an

“operational reason” to withhold information about him from Mexico City, though

she herself had not been read into whatever “hanky-panky” may have been taking

place.

After

the interview, Morley and Newman stopped their recorders, thanked Roman, and

stepped outside. “John and I looked at each other and said, ‘Oh my fucking

God,’” Morley told me. They had coaxed from a highly placed former CIA

official, on tape and on the record, an acknowledgment that top CIA officers in

Washington had been keenly interested in Oswald before the assassination, so

much so that they had intentionally misled their colleagues in Mexico about him

for reasons apparently related to an operation of some kind.

Later,

Morley spoke with Edward Lopez, a former researcher for the HSCA, where he had

been tasked with investigating the CIA. Lopez said, “What this tells people is

that somehow the Agency had a relationship with Lee Harvey Oswald prior to the

assassination and that they are covering it up.” At the Post, Morley brought

the story not to “Outlook” but to the more prestigious “National” section. “And

naïve as I was, I thought, This is a great fucking story, and they’re going to

love it!” Morley told me.

“National”

editors did spend several months working with him, but it was decided that the

story could not run in the paper’s news section. There was no explicit

prohibition on Kennedy-assassination stories, an editor told me, but if

‘National” was going to publish something “on such an explosive topic,” the

paper’s leadership “would’ve wanted it nailed down real tight.”

Morley

took the piece to “Outlook,” “an implicit downgrading” in his view. It ran in

the spring of 1995. A senior editor took him aside afterward to say, “Jeff,

this isn’t good for your career.” “And to me,” Morley recalled, “that was like,

‘Wow, this really is a good story!’”

One

of the more damning revelations of the past few decades is that the Warren

Commission very likely reached its lone-gunman verdict, or rather received it

from on high, before it had begun its investigation. This conclusion emerged

from later statements by the commissioners; from recordings of the phone calls

of President Johnson, in which he made clear that it was of paramount

importance to show that Oswald had no ties to either the Soviets or their Cuban

allies, so as to avoid “a war that can kill 40 million Americans in an hour”;

and, most famously, from a declassified memo prepared for the White House by

Assistant Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach on November 25, one day after

Oswald’s death.

“The

public must be satisfied that Oswald was the assassin; that he had no

confederates who are still at large; and that evidence was such that he would

have been convicted at trial,” Katzenbach wrote. “Speculation about Oswald’s

motivation ought to be cut off, and we should have some basis for rebutting

thought that this was a Communist conspiracy or (as the Iron Curtain press is

saying) a right-wing conspiracy to blame it on the Communists.” This evidence

certainly does not prove that the Warren Commission was a fraud, or that its

conclusions were necessarily wrong, but it does suggest quite strongly that, at

its highest levels, the commission was not interested in discovering anything

other than Oswald’s sole and apolitical responsibility for the assassination.

Likewise,

the Senate’s Church Committee, convened in 1975 to study abuses by the

intelligence services, found that the Warren Commission had not received the

honest cooperation of the FBI or CIA, which withheld “facts which might have

substantially affected the course of the investigation.” The CIA in particular

avoided mention of its various plots to assassinate Fidel Castro, one of which

had involved a Cuban high official who had, in a meeting in Paris on the very

day of Kennedy’s killing, received from a CIA handler the poison pen with which

he was supposed to carry out his task. These activities were, in addition to

being closely held secrets, patently illegal, and it is understandable that the

CIA would not want to disclose them. But it is just as obvious that a thorough

investigation of the assassination would have required their disclosure. Castro

had stated publicly, for instance, that he would retaliate if he ever

discovered that the U.S. was trying to have him killed; the fact that the

Agency had been doing precisely this at the time of the assassination would

have been a clear investigative lead.

Allen

Dulles, a former director of the CIA who sat on the Warren Commission, could

have informed his fellow commissioners of the plots. He elected not to. Dulles

hated Kennedy, whom he considered a pinko and an interloper and who had

unceremoniously fired him as CIA director after the Bay of Pigs. Arlen Specter,

who became a senator 15 years after serving on the Warren Commission, used to

tell a story about Dulles, which was recounted to me by Carl Feldbaum,

Specter’s Senate chief of staff. The commissioners were at one point solemnly

passing round Kennedy’s bloodied necktie from November 22; a bullet hole was

clearly visible. When the garment came to him, Dulles, puffing on his pipe,

examined it for a moment and then, passing it along, remarked, “I didn’t know

Jack wore store-bought ties.”

In

addition to the Castro plots, the Church Committee was particularly severe with

the CIA for its lack of curiosity over “the significance of Oswald’s contacts

with pro-Castro and anti-Castro groups for the many months before the

assassination.” Oswald’s behavior in the summer of 1963 looked to many critics

like that of some sort of spy or agent provocateur. Senator Richard Schweiker,

who chaired the Church subcommittee on the Kennedy assassination, said of

Oswald, “Everywhere you look with him, there are the fingerprints of

intelligence.”

The

HSCA investigation, begun in 1977, took a special interest in Oswald’s Cuban

contacts, and in particular his interactions with an anti-Castro group known as

the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil, or DRE. The Warren Commission had

reported on the DRE but had never been informed that the group was founded,

funded, and closely managed by the CIA.

Prior

to the investigation, the HSCA’s lead counsel, G. Robert Blakey, obtained a

formal agreement for extensive access to the Agency’s files. “They agreed to

give us everything,” Blakey, who is now professor emeritus at Notre Dame,

recalled recently. “At some stage, they decided that that was not a good idea.”

In 1978, after the HSCA had begun seeking information about the DRE, the CIA

named a new liaison to the committee, a notably severe, sharp-dressing senior

officer named George Joannides. “He kind of gave the impression of brooking no

lightheartedness,” Dan Hardway, a lawyer who dealt extensively with Joannides

as an HSCA researcher, told me. Hardway recalled seeing Joannides smile only

once, when he brought out a record that was almost entirely redacted. Hardway

was furious. “And George was just bouncing,” he said, “just bouncing on his

toes.”

Joannides

was presented as a “facilitator,” but his actual function seemed to be to “give

as little as possible, as slow as possible, and basically wait us out,” Blakey

said; the committee’s investigation into the DRE in particular was

“frustrated.” “Not ‘frustrated’ because we didn’t get what we wanted,” Blakey

said. “We didn’t get anything.” “Joannides screwed us,” Hardway told me.

Joannides’s

stonewalling has never been explained by the CIA. It may be instructive to

note, however, that not long ago the Agency admitted, albeit not publicly, that

it intentionally misled the Warren Commission. A report prepared in 2005 by CIA

chief historian David Robarge and declassified in 2014 claimed that Agency

officials engaged in a “benign cover-up” in order to prevent the discovery of

the Castro plots. It is entirely possible that the CIA’s apparent efforts to

keep the HSCA away from the DRE were similarly “benign.” But the purpose would

not have been to cover up the Castro plots: The Castro plots had by then been

publicly acknowledged. If the CIA was using Joannides to prevent the discovery

of some damaging secret, it was evidently something else.

Before

meeting Jane Roman, Morley was “still kind of in lone-gunman-land,” he told me.

But the story of the October 10 cable convinced him that the Agency had perhaps

been using Oswald in some way and that it might bear some responsibility for

the assassination, though whether by design or mistake — “complicity” or

“incompetence,” in Morley’s words — he could not say. He began to look into

Oswald’s connections to the DRE.

In

the early 1960s, the CIA supported a number of Cuban exile groups, helping them

to conduct psychological warfare, gather intelligence, and run paramilitary

operations in Cuba. The DRE, based in Miami, was among the largest and most

influential; at one point, it was receiving $51,000 from the Agency every

month, the equivalent of about half a million dollars today. Its leaders were

profiled in Life.

In

1962, the CIA’s deputy director for operations, Richard Helms, summoned the

DRE’s young secretary-general, Luis Fernandez-Rocha, to his office in Langley.

“You, Mr. Rocha, are a responsible man,” Helms said, according to a memo

released under the JFK Act. “I am a responsible man. Let’s do business in a

mature manner.” Helms assured Fernandez-Rocha of his “personal interest in this

relationship” and said he would be appointing a new case officer for the DRE, a

capable man who would report directly to him.

Oswald

encountered the DRE the following year in New Orleans. His behavior during that

period was, as the Church Committee noted, perplexing. He presented himself

publicly as a member of the New Orleans branch of the Fair Play for Cuba

Committee, a controversial pro-Castro group, carrying a membership card signed

by the branch president, A.J. Hidell. And yet no such branch existed, nor any

such person. (When he was arrested in Dallas, Oswald carried a forged

identification card bearing his picture and the name of “Alek James Hidell.”)

At the same time, he seemed to be in contact with various opponents of the

Castro regime. In August, Oswald approached a man named Carlos Bringuier,

presenting himself as a fellow anti-Communist and offering his military expertise

to help train rebel Cuban fighters. Bringuier was the DRE’s delegate in New

Orleans.

A

few days later, a friend told Bringuier that Oswald was nearby, on Canal

Street, handing out pro-Castro leaflets (“HANDS OFF CUBA!”). Bringuier went to

confront Oswald; the men were arrested for fighting. Before his release from

jail, Oswald asked to speak with an FBI agent, to whom he took pains to explain

that he was a member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. In a radio appearance

shortly thereafter, Oswald debated Bringuier on the topic of Kennedy’s Cuba

policy. Following the debate, a coalition of anti-Castro groups issued an “open

letter to the people of New Orleans” warning that Oswald was a dangerous

subversive.

Three

months later, the DRE distinguished itself as the source of the Kennedy

assassination’s very first conspiracy theory. On November 22, DRE operatives

called their contacts in the media to report that they knew the alleged

assassin and that he was quite obviously an agent of the Cuban regime.

Bringuier made the front page of the next morning’s Washington Post.

At

the archive, Morley found monthly progress reports on the DRE that spanned the

full era of CIA backing, from 1960 until 1966, except for a conspicuous

17-month gap around the assassination. Morley did find a DRE memo from the

missing period, however. It was addressed simply “To Howard.” He assumed this

referred to the DRE’s case officer. “So I thought, Well, this guy Howard, if

he’s around like Jane Roman was around, that would be a really good story,”

Morley said. Morley was able to convince the Post’s investigations editor, Rick

Atkinson, to send him to Miami, where he hoped to ask the former leaders of the

DRE who Howard was. He flew down from Washington in the fall of 1997.

The

DRE men remembered Howard distinctly. He dressed in tailored suits, wore a

pinkie ring, and was memorably uncongenial. Fernandez-Rocha, the DRE’s former

secretary-general, recalled meeting him as frequently as a few times a week for

coffee at a Howard Johnson’s. The group’s previous case officer had been a

lovely man, “but he was a sergeant,” Rocha told Morley. “When I was dealing

with this guy Howard, I was talking to a colonel.”

When

Morley returned to Washington, he brought the question of Howard to the

Assassination Records Review Board. The JFK Act had created the ARRB, an

independent commission with a staff of about 30 lawyers and researchers, to

oversee the initial phase of declassification. The board’s primary task was to

identify all assassination-related records in the possession of the CIA, FBI,

and other government entities. To the displeasure of some of those bodies, its

interpretation of “assassination-related” proved to be sweeping. “We didn’t

just dabble in records,” John Tunheim, who chaired the review board until its

conclusion in 1998, told me. “We tried to answer as many questions as we

could.” The ARRB had in fact already been pressing the CIA for information about

the DRE for a year; it added Howard to its request in 1997, asking that the CIA

identify him.

In

a memo, the Agency responded that the “missing” reports had likely never

existed, and that “Howard” was neither a known pseudonym, nor a “registered

alias,” nor the true name of any DRE case officer. “The use of ‘To Howard’

might have been nothing more than a routing indicator,” the Agency suggested.

Morley

found this explanation wanting. (“A routing indicator with a pinkie ring!” he

joked to me.) The ARRB soon issued its final report and disbanded. Shortly

thereafter, however, Morley got a call from T. Jeremy Gunn, the board’s lead

investigator and chief counsel. An ARRB analyst had apparently managed to

identify Howard by reviewing the personnel file of an operations officer known

by the pseudonym Walter D. Newby. Newby had become the DRE’s handler in

December 1962 and served for 17 months — precisely the period of the missing

records. Five of Newby’s job evaluations, or “fitness reports,” had been

declassified. The National Archives faxed them to Morley.

The

man in the reports certainly seemed to correspond with the “Howard” described

by Fernandez-Rocha and the other DRE men. One evaluation from 1963 made note of

his “firmness” and his ability “to render a decision without waste of motion.”

A later report commended Newby’s “distinct flair for political action

operations” — he was by then chief of the covert-action branch at the CIA’s

Miami station — but acknowledged a “tendency to be abrupt with subordinates.”

Of most interest to Morley, however, was an evaluation from many years after

the Kennedy assassination when Newby had been called out of retirement for an

assignment of a different sort under his real name. In 1978 and 1979, this

report indicated, Newby had served as liaison to the HSCA, where he was lauded

for “the cool efficacy with which he handled an unusual special assignment.”

His true name was George Joannides.

At

the HSCA, Joannides had been specifically assigned to handle queries about the

DRE and its relations with the CIA. The Agency had assured the committee that

he had no connection whatsoever to the matters under investigation; that, in

fact, he was merely an Agency lawyer and had not been “operational” in 1963.

These assurances were self-evidently false. At one point, Joannides informed

the committee that the identity of the DRE’s case officer at the time of the

Kennedy assassination — Joannides himself — could not be determined.

Morley

called Blakey, the committee’s chief counsel and lead investigator. “He went

ballistic,” Morley recalled. “They flat-out lied to me about who he was and

what he was up to,” Blakey told me. “I would have put him under subpoena and

put him in a hearing and talked to him under oath.” Blakey released a written

statement arguing that Joannides and his superiors were guilty of obstruction

of justice. “I no longer believe,” it said, “that we were able to conduct an

appropriate investigation of the Agency and its relationship to Oswald.”

Twenty

years after the CIA lied about Joannides to the HSCA, the Agency seemed to have

done the same to the ARRB. I asked Tunheim, the board’s chair, if he believed

that the Historical Review Group, the CIA office assigned to work with the

ARRB, had taken part in the deception. “I think they were very truthful with us

on what they knew,” he said. “But whether they knew the whole story or were

told the whole story, or were even misled by people within the Agency, I can’t

answer that.”

Morley

brought the Joannides story to the Post but had no luck. I asked Rick Atkinson,

the editor who paid for his trip to Miami, if he remembered anything about it.

“I vaguely recall Jeff having an interest in the assassination,” Atkinson, a

three-time Pulitzer winner, wrote in an email. “Frankly it bored me.” Morley’s

career at the Post had begun to stagnate. He became a metro reporter and then a

web editor at a time when newspaper websites were widely viewed by newspaper

employees as hopeless backwaters. He eventually managed to publish a piece on

Joannides in the Miami New Times, a South Florida alt-weekly.

In

his spare time, Morley continued his reporting. Joannides had died in 1990.

(His obituary in the Post claimed he was a “retired lawyer at the Defense

Department.”) But Morley was able to reach several of his aging former

colleagues. They recalled a self-possessed and cultivated gentleman operator,

with connections at the highest levels of the Agency, “not one of the wild

men,” in the words of Warren Frank, who knew Joannides in Miami. There,

Joannides managed an annual budget of $2.4 million, the equivalent of ten times

that today.

In

July 2003, Morley sent the CIA a request, under the Freedom of Information Act,

for all records pertaining to Joannides. “The public has the right to know what

he knew,” he wrote. The CIA responded with a letter encouraging him to contact

the National Archives. With the help of the FOIA lawyer James Lesar, Morley

sued.

The

500 pages of documents that ultimately emerged from Morley v. CIA went well

beyond the scope of the five fitness reports released under the JFK Act. Morley

was given the Agency’s personnel photograph of Joannides — a menacingly

well-kempt man of middle age, dark eyes recessed in shadow, jaw set in an

ambiguous glower — as well as documents suggesting that he had spent time in

New Orleans and that he had been granted access to a particularly sensitive

intelligence stream in June 1963. Many of the documents were heavily redacted;

the Agency also acknowledged the existence of 44 documents on Joannides from

the years 1963, 1978, and 1979 that it refused to release in any form. “The CIA

is saying very clearly, ‘This is top secret, please go away,’” Morley told me.

“So that’s where the story is, right? I mean, they’re telling me what’s

important, and I believe them.”

Until

recently, if asked what happened in Dallas on November 22, 1963 — the “cosmic

question,” as he once put it — Morley deflected. In his writing, he tended to

address it only obliquely and declined to articulate an overarching theory,

except to say the Warren Commission got it wrong. Over the years, he had made

all manner of damning discoveries; what they added up to, beyond a cover-up,

Morley professed not to know.

Increasingly,

though, he has been willing to theorize. Last year, he published an article on

JFK Facts under the headline, “Yes, There Is a JFK Smoking Gun.” “Now, after 28

years of reporting and reflection, I am ready to advance the story,” he wrote.

“Jane Roman was correct. A small group of CIA officers was keenly interested in

Oswald in the fall of 1963. They were running a psychological warfare

operation, authorized in June 1963, that followed Oswald from New Orleans to

Mexico City later that year. One of the officers supporting this operation was

George Joannides.”

Morley

believes Oswald was an “agent of influence,” he told me, or, as at least one

CIA officer put it at the time, a “useful idiot” of the Agency. In New Orleans,

perhaps he’d been encouraged to prove his leftist bona fides by claiming to be

a member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. The trip to Mexico seems to have

been part of “some kind of probing intelligence operation,” Morley said. But

why go to all this trouble? Why hide the operation for so long? Why Oswald?

The

parsimonious explanation, Morley believes, is that a “public legend” was being

constructed: Someone in the Agency was setting Oswald up to take the fall for

the coming assassination. Morley’s suspicion falls most heavily on Angleton,

whose office controlled Oswald’s file from the moment it was opened. “Was

Angleton running Oswald as an agent as part of a plot to assassinate President

Kennedy?” Morley wondered in The Ghost, his 2018 biography of Angleton. “He

certainly abetted those who did. Whoever killed JFK, Angleton protected them.”

Morley told me he wonders about Bill Harvey, the Agency’s assassinations chief,

as well as David Atlee Phillips, who helped found the DRE and was allegedly

once seen in Dallas with Oswald. Joannides would have been an “unwitting

co-conspirator,” Morley believes, oblivious to what his superiors were doing

with him until the moment Kennedy was shot, and then brought in as the cleanup

man.

This

is all possible but also extremely speculative. Why risk speaking it aloud?

Certainly he has been criticized for it. In a review of The Ghost, the author

and intelligence historian Thomas Powers submitted that Morley had “suffered a

kind of mid-life onset of intellectual hubris,” convincing himself that he knew

the truth of the assassination even if the evidence had yet to materialize. A

number of Morley’s friends and fellow researchers expressed some version of

this concern to me as well. “Sometimes I worry for Jeff,” said the journalist

Anthony Summers, the author of a respected assassination book called Not in

Your Lifetime. “Commitment to a story is a virtue. But sometimes, I think, his

writing goes beyond what the facts justify. He surprises me with his

certainties.” The assassination has been known to drive people to unreason.

“They tend to be smart people who are wide readers and trust their ability to

figure things out,” Powers, the intelligence historian, told me. “It’s a

subject that people get lost in. And sometimes they’re seen again, and

sometimes not.”

Morley’s

rigor has unquestionably eroded a bit in recent years. In August, he published

a short post on JFK Facts about a Kennedy-administration memo proposing a

“drastic” reorganization of the CIA. He’d just discovered the document; 60

years after the fact, it was still partially redacted. Why? “To protect the

CIA’s impunity,” Morley declared. Fred Litwin, an anti-conspiracist

assassination buff and blogger, pointed out that Morley’s new document was

merely an alternate copy of a famous memo by Kennedy adviser Arthur Schlesinger

Jr. “Will Jefferson Morley correct this error?” Litwin wondered. He never did.

A

few weeks earlier, Morley had convinced Peter Baker, the prolific New York

Times White House correspondent, to write about Ruben Efron, a CIA officer who

had once been tasked, as part of an illegal program run by Angleton, with

reading Oswald’s mail. Efron’s name seemed to have been the sole remaining

redaction in Oswald’s pre-assassination CIA file, but it had just been

released. “People say there’s nothing significant in these files?” Morley told

Baker. “Bingo! Here’s the guy who was reading Oswald’s mail, a detail they

failed to share until now. You don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to think

it’s suspicious.” (“I keep a very open mind,” Baker told me.) But Efron’s name

had in fact been released a few times over the years in documents elsewhere. Paul

Hoch, who is widely viewed as the doyen of serious assassination research, saw

no meaning in the new release. “Knowing his name doesn’t add anything,” Hoch

told me. Certain colleagues have begun referring to “good Jeff” from the first

25-odd years and “bad Jeff” from more recently.

On

the one hand, Morley’s new willingness to speculate strikes me as a natural and

reasonable evolution. Like all investigations, his has always been driven by

hypothesis, and he has now been improving and refining his theory of CIA

involvement for three decades. On the other, advancing a theory of the Kennedy

assassination is what the nuts do. When I asked him what had caused the change

in approach, he grew testy. “The evidence,” he said.

We

were drinking coffee on the back porch of the house he would soon have to

leave. “Do my critics have another explanation for what Joannides was doing and

who he was working for?” he asked. “People bitch about my interpretation. I

brought new facts to the table which they can’t explain, or have not explained,

and those facts are indisputable.” The twinkly music of an ice-cream truck

floated up from somewhere. “People will wonder, ‘Why did you devote all this

time and effort to it?’” Morley said. “I was very careful because I’ve seen it

drive so many people crazy. This is not going to drive me crazy.”

Despite

his best efforts, since 2008 he has not extracted any further documentation on

Joannides from the CIA. His FOIA lawsuit came to an end in 2018, when

then–District Judge Brett Kavanaugh and a colleague ruled that his attorney,

Lesar, would not have his fees paid by the CIA. The Agency and a lower court

deserved “deference piled on deference,” the judges held. (On the same day,

Trump nominated Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.) There are scarcely any CIA

officers from Joannides’s time left to talk to. The DRE men have begun to die.

This

summer, President Biden endorsed “Transparency Plans” proposed by the CIA and a

handful of other agencies, effectively delegating oversight of any additional

declassification to the agencies themselves. “He’s washing his hands of it,”

Tunheim, the ARRB chair, told me. No clear mechanism exists to compel the

release of any further documents, ever.

In

its executive session of January 27, 1964, the Warren Commission took up a

rumor, passed on by the attorney general of Texas, that Lee Harvey Oswald had

been working undercover for the FBI or perhaps the CIA. The commissioners did

not seem to take the claim very seriously, but they did wonder how one might

verify such a thing. Having on hand a former director of the CIA, the group

naturally sought his insights. Allen Dulles told his fellow commissioners, to

their apparent disbelief, that one could not expect an intelligence service to

be knowledgeable in such matters or truthful if it were.

The

recruiting officer would of course know of an agent’s recruitment, Dulles said,

but he might be the only one, and “he wouldn’t tell.”

“Wouldn’t

tell it under oath?” asked Justice Warren.

“I

wouldn’t think he would tell it under oath, no,” Dulles responded. “He ought

not tell it under oath.” Nor could one expect to find any written record of

such an agent. “The record might not be on paper,” Dulles said, or might

consist of “hieroglyphics that only two people knew what they meant.” He

clarified later, “You can’t prove what the facts are.”

The

impulse to try may be stronger than reason. I asked the CIA if Oswald had ever

been “an agent, asset, source, or contact” of the Agency. A spokesperson

replied, in writing: “CIA believes all of its information known to be directly

related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 has already

been released. Likewise, we are not aware of any documents known to be directly

related to Oswald that have not already been made part of the Collection.” I

confess to finding it striking that the Agency did not say, “To the best of our

knowledge, no.” Morley would call this, to use the Post’s famous Watergate

phrase, a “non-denial denial.” He would no doubt apply the same term to the

Agency’s “decline to comment’s on my questions about why Joannides had

concealed his role in 1963 from Congress and about whether the CIA had

“cooperated fully and faithfully” with the Warren Commission, with the HSCA, or

with the ARRB. But then, why take the Agency at its word, whatever it may be?

Assuming

for the sake of argument, however, that the CIA did generate a record of Agency

activity around Oswald, and that this record was faithful, would it be

reasonable to hope to one day find it? Though he has spent most of his adult

life in precisely this pursuit, Morley told me he does not believe it would.

During the 17-month gap in reporting on the DRE, for instance, he suspects

Joannides produced regular reports and that those reports mentioned Oswald; he

suspects the reports were sent directly to Helms at headquarters; and he

suspects Helms destroyed them in 1973, when he left the Agency. There are in

fact numerous instances of ostensibly “assassination-related” documents being

irregularly destroyed. I find this devastating myself. Burning records is not

an especially subtle method of concealing the past, but the bluntness is what

is so distressing. If this is the way the CIA has been playing, the game has

been all but hopeless from the start.

And

yet the archive pulls at you, irresistible, irrational, a form of gravity upon

the mind. I visited the National Archives in September. The President John F.

Kennedy Assassination Records Collection is held in a glassy modern building in

the woods beyond the University of Maryland in College Park. The collection now

holds about 6 million pages, kept in gray, five-inch, acid-free paperboard

Hollinger boxes, maintained at constant temperature and humidity in stacks

accessible only to archivists with the requisite security clearance. I sat in

the airy reading room, afternoon sun streaming in over the treetops, and leafed

through the CIA’s pre-assassination file on Oswald.

I

found the October 10 cable, bearing Jane Roman’s name and reporting, falsely,

that “LATEST HDQS INFO” was from May 1962. I found a small photograph of the

Mexico Mystery Man. I found a typewritten letter addressed to Allen Dulles,

dated November 11, 1963, from a man who wished to infiltrate the American

Communist Party for the CIA; it was accompanied by a slip marked “FOR MR.

ANGLETON” with a handwritten note reading, “Some useful ideas here — you will

have many more,” and signed, “Allen.” I found, on paper gone gauzy and

translucent with time, a memorandum to the Warren Commission from the CIA about

redactions. There were things in the files sent over by the Agency that, in the

Agency’s estimation, the commission did not need to know. “We have taken the

liberty,” Richard Helms advised, “of blocking out these items.”

Earl

Warren, born in the 19th century, died trusting in the good faith of men such

as Helms, Angleton, and Dulles and of institutions such as theirs. “To say now

that these people, as well as the Commission, suppressed, neglected to unearth,

or overlooked evidence of a conspiracy would be an indictment of the entire

government of the United States,” he wrote in his memoirs. “It would mean the

whole structure was absolutely corrupt from top to bottom.” Warren evidently

found the idea of a plot of any sort too monstrous to contemplate. Dulles, of

all people, had once tried to make him understand that the world wasn’t quite

as honest as he thought. The proof was there, if only one could see it.

No comments:

Post a Comment