The

most celebrated genius in human history didn't just revolutionize physics, but

taught many valuable lessons about living a better life.

When

it comes to living your best life, Albert Einstein — notorious as the greatest

physicist and genius of his time, and possibly of all-time — probably isn’t the

first name you think of in terms of life advice. You most likely know of

Einstein as a pioneer in revolutionizing how we perceive the Universe, having

given us advances such as:

- the constancy of the speed of light,

- the fact that distances and times are not absolute, but relative for each and every observer,

- his most famous equation, E = mc²,

- the photoelectric effect,

- the theory of gravity, general relativity, that overthrew Newtonian gravity,

- and Einstein-Rosen bridges, or as they’re better known, wormholes.

But

Einstein was more than just a famous physicist: he was a pacifist, a political

activist, an active anti-racist, and one of the most iconic and celebrated

figures in all of history.

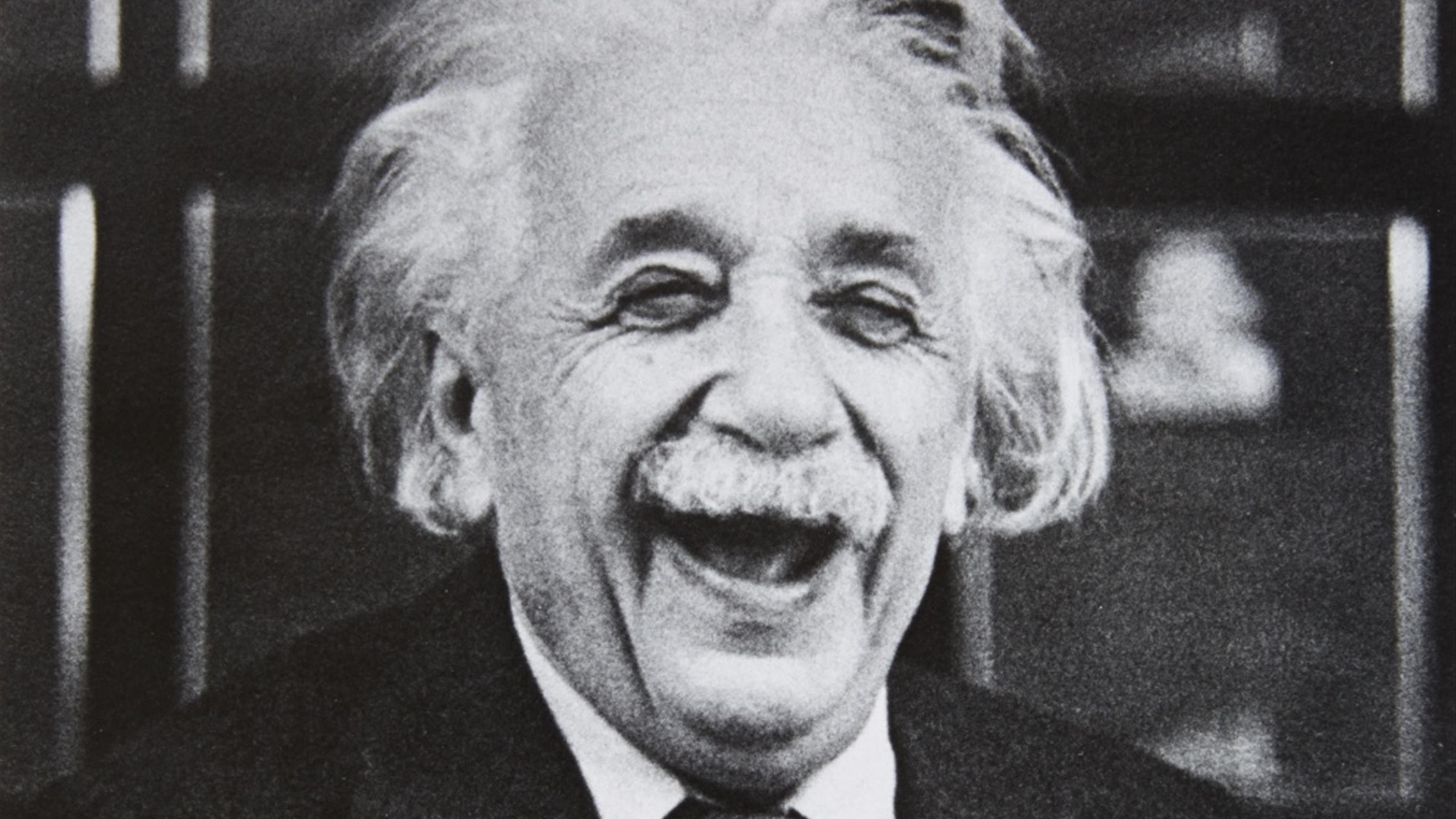

He

was also known for his unconventional behavior in a variety of ways that

flouted social norms, including his unkempt hair, his witty humor, and his

unrelenting hatred of socks. But less well-known is Einstein’s freely-given

life advice to many of his friends, acquaintances, and contemporaries, which

are perhaps even more relevant today, in the 21st century, than when he

initially doled out his words of wisdom and compassion. Taken from the book The

Einstein Effect, written by the official social media manager of the Einstein

estate, Benyamin Cohen, these rules for a better life go far beyond physics and

are relevant to us all. Here are, perhaps, the best and most universally

applicable lessons from Einstein himself.

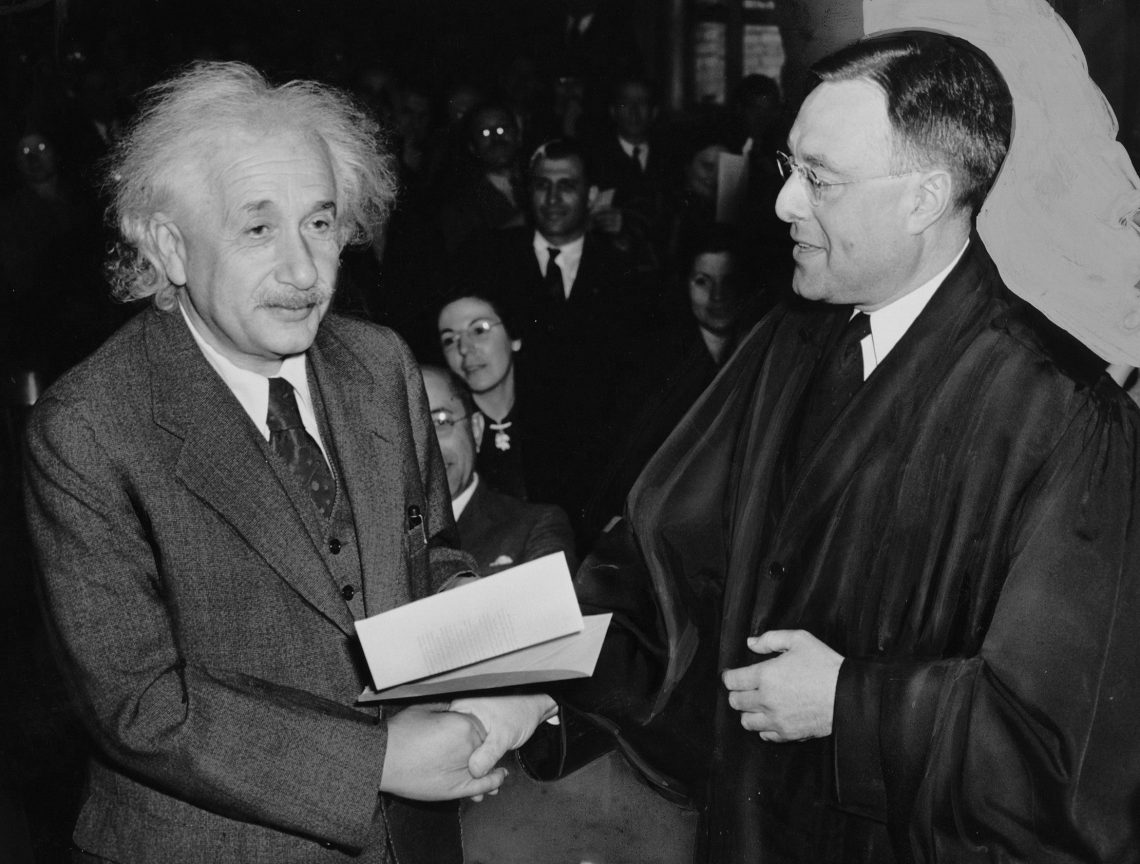

Einstein,

shown here in 1940 receiving American Citizenship, was known around the world

for his disheveled appearance and always wearing the same few sets of clothes,

perhaps even better than he was known for his scientific theories.

Rule

#1: Expend your efforts on the things that matter.

When

you think of Einstein’s appearance, the word “disheveled” may come to mind. His

overgrown, uncombed hair, his ratty, worn-out, often smelly clothing, his shoes

without socks, etc., all were notoriously slovenly. But none of that bothered

Einstein, who in his later years wore what could be considered almost a

uniform: a signature grey suit, sans the traditional sport coat, with a leather

jacket in its place. (And, of course, with shoes and no socks.)

This

idea, of wearing simple but functional clothing that puts the wearer at ease

with themselves, has been made famous in recent years by tech entrepreneurs who

have their own signature style:

- Steve Jobs and his infamous blue jeans and black turtlenecks (a style copied by Elizabeth Holmes),

- Jeff Bezos, who wears blue jeans with short-sleeve, monochrome, collared shirts,

- Mark Zuckerberg, who prefers blue jeans and T-shirts,

- Satya Nadella, who typically wears slacks, polo shirts, and Lanvin shoes,

- and Jack Dorsey, whose all-black outfits often include a hat, hoodie, or jacket,

This

1937 photo shows Einstein in his New Jersey home with violinist Bronislaw

Huberman. Einstein is wearing his favorite outfit: a suit with his Levi’s

leather jacket and shoes with no socks.

If

you have a lot of decisions to make each day, or a lot of work that requires

mental effort in any sense, cutting down on your overall mental load is of

paramount importance if you want to avoid what’s known as decision fatigue:

where our ability to make good decisions degrades as we become more tired from

relentlessly having to make choices.

As

fashion journalist Elyssa Goodman wrote, “Uniform dressing has roots in not

just physical but mental efficiency. People who have to make immense decisions

every day will sometimes choose a consistent ensemble because it allows them to

avoid decision fatigue, where making too many unrelated decisions can actually

cause one’s productivity to fall off.”

It’s

a way to economize your efforts: to put them where they’re most needed, at the

expense of not wasting them on spurious or unimportant matters. In other words,

choosing not to put effort into the things that are superfluous to what’s

actually important to you is a way to become more mentally efficient, which

frees up your mind to focus on what actually matters most to you. Einstein’s

lack of effort into his personal presentation extended to his disdain for going

to the barber, as well as his often nearly-illegible penmanship. But the

rewards, of focusing his mind on what was truly important to him, led him to a

rich, fulfilling life.

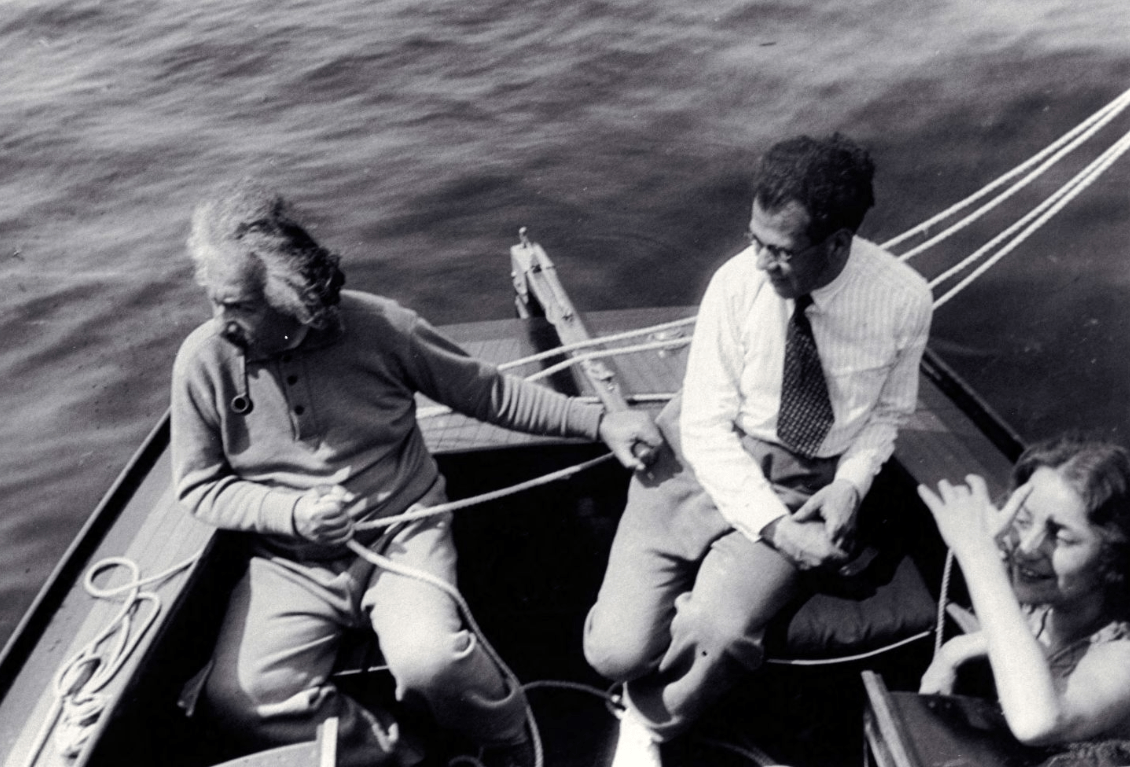

This

1930 photograph shows Albert Einstein sailing with his step-daughter Ilse and

her husband Rudolf Kayser in Germany, less than 3 years before he fled his home

country for the United States.

Rule

#2: Do things you love, even if you’re terrible at them.

While

many of Einstein’s passions extended far beyond physics — including a love of

baked goods and a penchant for playing the violin — perhaps the one he enjoyed

the most was sailing. As Einstein wrote, “A cruise in the sea is an excellent

opportunity for maximum calm and reflection on ideas from a different

perspective.” His second wife (and cousin), Elsa, added that “There is no other

place where my husband is so relaxed, sweet, serene, and detached from routine

distractions; the ship carries him far away.” By focusing on something mundane,

Einstein’s mind was free to wander, frequently leading him to exciting new

ideas.

Einstein,

however, was completely inept at sailing, and was at best a wildly inattentive

sailor. He would frequently lose his direction, run his boat aground, or have

his mast fall. Other sailing vessels frequently had to beware of Einstein’s

ship, as he was a hazard to himself and others, refusing to wear a life vest

despite being unable to swim. Boaters and even children routinely rescued him,

and having his boat towed back to shore was a frequent occurrence. But the

serenity Einstein experienced while sailing was unparalleled, giving him a

mental freedom that we should all aspire to for ourselves.

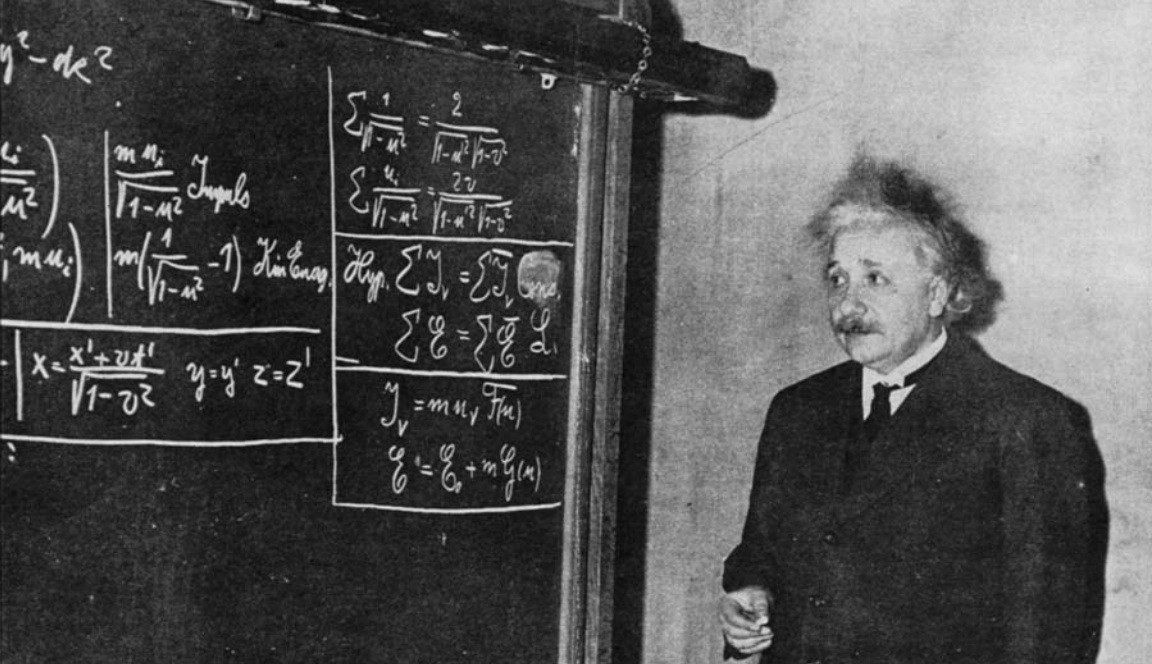

This

1934 photograph shows Einstein in front of a blackboard, deriving special

relativity for a group of students and onlookers. Although special relativity

is now taken for granted, it was revolutionary when Einstein first put it

forth, and it isn’t even his most famous equation; E = mc² is.

Rule

#3: Have a puzzle mindset.

Think

about the problems that we face, both as individuals and collectively, as a

civilization. These could be financial, environmental, health-related, or

political, for example, as those arenas affect us all. Do you view these

problems as crises? If you do, you probably feel despair at them, as there’s

very little that’s empowering about facing a crisis. But if you view them as a

puzzle, you might be inclined to think about a fresh approach to solving them.

In this regard, Einstein was pretty much the prototype individual for someone

who viewed every difficulty he faced as a puzzle to be solved: in physics and

beyond.

Consider

his oft-misunderstood but most famous quote, “Imagination is more important

than knowledge.” While many people had looked at the puzzle of objects moving

near the speed of light before — including other geniuses like FitzGerald,

Maxwell, Lorentz, and Poincaré — it was Einstein’s unique perspective that

allowed him to approach that problem in a way that led him to the revolution of

special relativity. With a flexible, non-rigid worldview, Einstein would easily

challenge assumptions that others couldn’t move past, allowing him to conceive

of ideas that others would unceremoniously reject out-of-hand.

The

identical behavior of a ball falling to the floor in an accelerated rocket

(left) and on Earth (right) is a demonstration of Einstein’s equivalence

principle. If inertial mass and gravitational mass are identical, there will be

no difference between these two scenarios. This has been verified to ~1 part in

one trillion for matter, and was the thought (Einstein called it “his happiest

thought”) that led Einstein to develop his general theory of relativity.

Einstein

was no stranger to having strongly held convictions about both life and

physical reality, but each of his opinions, even those he was most certain of,

were no more sacred to him than a mundane hypothesis. When one has a

hypothesis, or idea, the goal isn’t simply to find out whether that hypothesis

is right or wrong; in some sense, that’s the least interesting part of the

endeavor. The search for the answers, including figuring out how to perform the

critical test and interrogate the Universe itself in an effective manner, was

what truly got Einstein excited.

His

thought-experiments were among the most creative approaches ever taken by

physicists, and that line of thought has been adopted by a great many

scientists ever since who wish to avoid what’s known as cognitive entrenchment.

What would a light-wave look like if you could follow it by traveling at the

same speed it traveled at? How would the light from a distant star be deflected

by the Sun’s gravity during a total solar eclipse? What experiments could one

perform to determine whether our quantum reality is pre-determined by variables

we cannot observe directly? Unlike a preacher who claims to be infallible, a

prosecutor who wants to convince you of their perspective, or a politician who

just wants to win your approval, having a puzzle mindset — i.e., the mind of a

scientist — is the only one that can lead you to novel discoveries, including

quite unexpected ones.

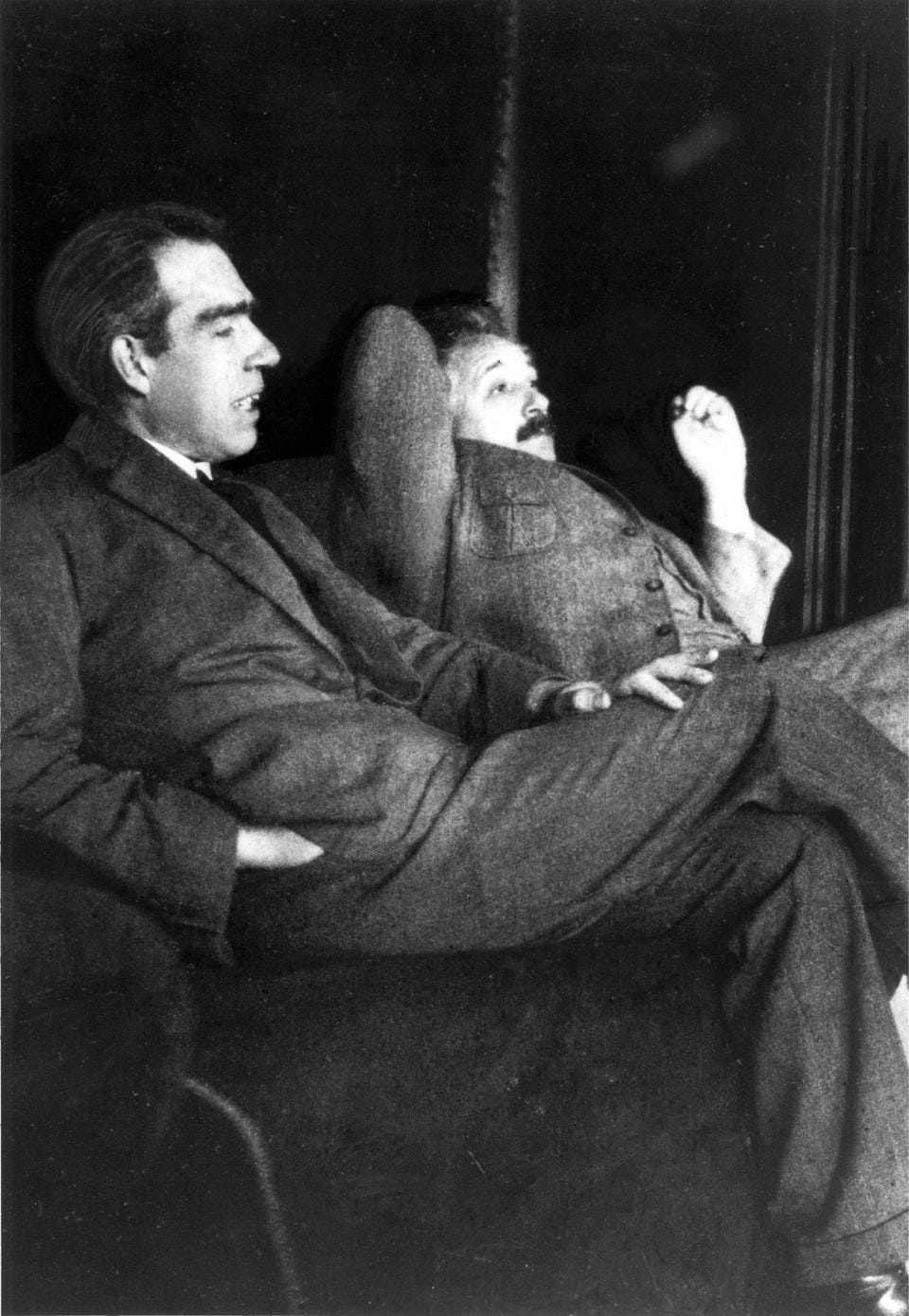

Niels

Bohr and Albert Einstein, discussing a great many topics in the home of Paul

Ehrenfest in 1925. The Bohr-Einstein debates were one of the most influential

occurrences during the development of quantum mechanics. Today, Bohr is best

known for his quantum contributions, but Einstein is better-known for his

contributions to relativity and mass-energy equivalence. Both were known for

thinking long and hard about the most difficult puzzles the Universe had to

offer.

Rule

#4: Think deeply, both long and hard, about things that truly fascinate you.

Over

the course of his long life, Einstein received many letters: from those who

knew him well to perfect strangers. When one such letter arrived on Einstein’s

desk in 1946, asking the genius what they should do with their life, the

response was as astute as it was compassionate. “The main thing is this. If you

have come across a question that interests you deeply, stick to it for years

and do never try to content yourself with the solution of superficial problems

promising relatively easy success.”

And

if you fail to arrive at the solution you’ve been chasing, don’t despair. As

Einstein wrote to his friend David Bohm, “You should not be depressed by the

enormity of the problem. If God has created the world, his primary worry was

certainly not to make its understanding easy for us.” Although Einstein was

most famous for the problems he did solve, there were plenty whose solutions

eluded him all his life: from finding a deterministic explanation for the

observed quantum behavior to the attempt to unify all of physics (including

gravity and the other forces) into one overarching framework.

Although

many have tried-and-failed (and continue to try-and-fail) to solve these and

other puzzles, the greatest joy and fulfillment is often to be found in the

struggle itself.

This

political cartoon, published in 1933, shows Einstein shedding his pacifist

wings to roll up his sleeves and take up a sword labeled “preparedness.”

Einstein would at this point call upon the friends of civilization all across

the world to unite against Nazi militarism.

Rule

#5: Don’t let politics fill you with either rage or despair.

Einstein

kept up with many friends and members of the public, but also with his extended

family. In correspondence with his cousin Lina Einstein, he offered a lesson

that many of us would do well to heed. “About politics to be sure, I still get

dutifully angry, but I do not bat my wings anymore, I only ruffle my feathers.”

How

many of us have seen a friend, acquaintance, or even total stranger make a

statement that filled us with outrage, and flew off the handle, filled with

righteous indignation, and launched into a tirade as a result? While that might

fulfill some primitive need in us to speak our mind and challenge what we see

as an unacceptable narrative, how often was such a response actually effective

in achieving any of our goals?

Sometimes,

it truly is important to intervene and go all-out: what Einstein refers to as

“batting our wings.” But at other times, in a lesson that King Bumi from

Avatar: The Last Airbender would heartily approve of, sometimes the best

response is to sit back, observe, think, and wait for the opportune, strategic

moment to take action down the road: “ruffling our feathers” for the time

being. It’s often a wise course of action, although for Einstein’s ill-fated

cousin, Lina, it’s worth mentioning that she died in the Nazi gas chambers in

1942. (Update: That was a different “cousin Lina” to Einstein. The Lina he gave

the advice to, his cousin Carolina, left Europe in the 1930s and emigrated to

Uruguay, where she lived out the rest of her days.)

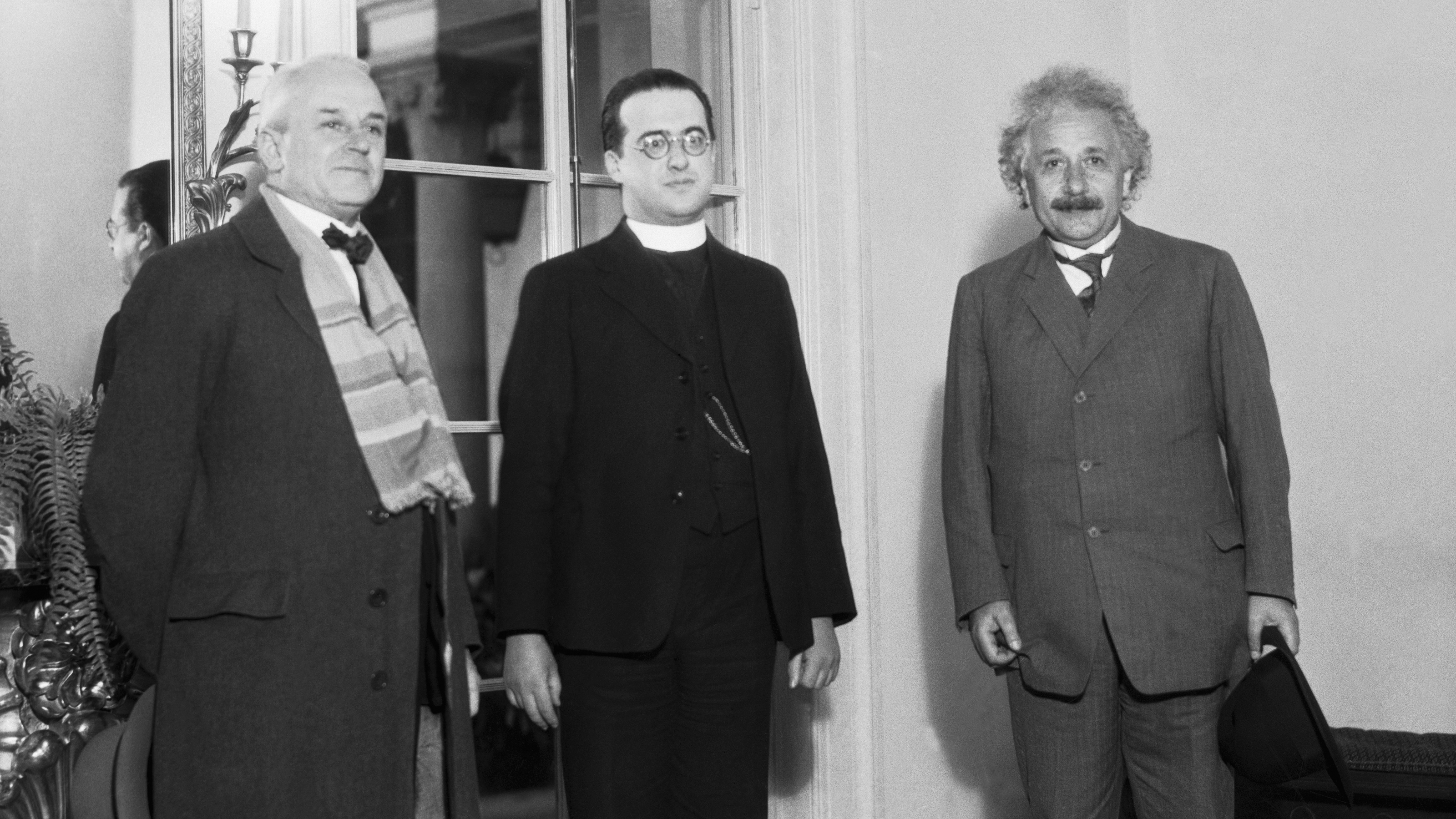

Albert

Einstein (right) is shown with physicists Robert Millikan (left) and Georges

Lemaître (center) several years after admitting his biggest blunder. If you

think that modern critics are harsh, one can only imagine how Lemaître must

have felt to receive a letter from Einstein calling his physics abominable!

Fortunately, just as Einstein was not dissuaded by the prevailing authorities

of his time, Lemaître and others were not deterred by Einstein’s declarations

of unsoundness.

Rule

#6: Blind obedience to authority is the greatest enemy of the truth.

Many

of us, upon hearing something that we are certain is either absurd, flawed, or

hopelessly corrupt, immediately and vociferously make up our minds to oppose

them, regardless of what the full suite of evidence actually indicates. Once we

abandon our critical thinking faculties because we are certain we know the

answer, we tend to simply go along with those who agree with us and oppose

those who espouse anything different. To Einstein, this represented the death

of the rational mind, which he called “collective insanity” or a “herd mind.”

Today, we would likely call it groupthink, and Einstein noted that it was often

driven by a prominent figure spouting propaganda.

Scientists,

including formerly reputable ones like Johannes Stark (Nobel Laureate and

founder of the Stark effect), formed an anti-relativity society that

discredited Einstein and his theory. Fueled by nationalism and anti-semitism,

Einstein and his ideas became a target, with one line of attack claiming

relativity was wrong and dangerous, and another line claiming it was brilliant

but that Einstein stole the idea from “real” (non-Jewish) scientists. It was

this course of action that eventually led to Einstein having a bounty placed on

his head, leading to him fleeing Germany for the United States. While Einstein

initially thought these machinations were silly, ridiculous, and harmless, he

later concluded that “Blind obedience to authority is the greatest enemy of the

truth.” In the era of fake news, this lesson is more important to assimilate

than ever.

During

the 1940s, Einstein himself gave a number of lectures to students who would

have, in the past, never have had access to a speaker such as himself. Einstein

made it a point to be generous with his time and with affording others access

to him, and was a prominent supporter of civil rights for all.

Rule

#7: Science, truth, and education are for everyone, not just the privileged

few.

Einstein

was often very critical of the United States Government, even after emigrating

in the 1930s and gaining his citizenship in 1940. The history of slavery and

ongoing segregation and racism, in particular, resonated with him the same way

that anti-Semitism did: as fundamentally dehumanizing as it was baseless. The

FBI began a file on Einstein in 1932, and it had burgeoned to more than 1400

pages by the time Einstein died in 1955, and Einstein’s anti-racist actions

were deemed fundamentally un-American by many (including Senator Joseph

McCarthy), but Einstein would not be deterred.

In

1937, Einstein invited black opera star Marion Anderson to stay at his house

when she was refused lodging at the local (segregated) hotel in Princeton. In

1946, Einstein took the revolutionary action of simply visiting Lincoln

University — the first degree-granting black college in the United States — and

lectured, speaking with students and answering questions. Delivering an address

to the student body, Einstein said:

“My

trip to this institution was on behalf of a worthwhile cause. There is a

separation of colored people from white people in the United States. That

separation is not a disease of colored people. It’s a disease of white people.”

In

1953, Einstein defended the academic freedom of William Frauenglass, a teacher

who taught about easing interracial tensions, in a letter published by The New

York Times. The following year, he further pushed for “the right to search for

truth and to publish and teach what one holds to be true.” In this day and age,

we can be certain that Einstein would have pushed for science, truth, and

education to be available to everyone. While certain physical properties may be

relative, like space and time, the joys, knowledge, and truths uncovered by

science belong to no one race, nation, or faction, but rather to all of

humanity.

The

quotes contained within were curated and lifted from Benyamin Cohen’s new book,

The Einstein Effect, and this piece contains affiliate links to that book.

No comments:

Post a Comment