February 2, 2024

Dozens of bodies of Palestinians

have been uncovered in a mass grave in a schoolyard in northern Gaza, with

witnesses saying they appeared to have been killed “execution style” by Israeli

forces. A human rights lawyer has said the killings are “clearly a war crime.”

Palestinians uncovered more than 30

bodies buried in northern Gaza in black bags with their hands and feet tied and

blindfolded, according to witnesses.

“As we were cleaning, we came across

a pile of rubble inside the schoolyard. We were shocked to find out that dozens

of dead bodies were buried under this pile,” one witness told Al Jazeera on

Wednesday. “The moment we opened the black plastic bags, we found the bodies,

already decomposed. They were blindfolded, legs and hands tied. The plastic

cuffs were used on their hands and legs and cloth straps around their eyes and

heads.”

Video and photos appearing to show

the bags containing the bodies show that they are zip-tied shut with tags with

barcodes and writing in Hebrew.

The witnesses’ accounts line up with

previous reports of Israeli soldiers killing Palestinians execution style in

other locations, including reporting that soldiers had lined up Palestinians,

including newborn babies, and shot them point blank at another school in

northern Gaza in December. Around the same time, Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor

reported that Israeli soldiers had been killing dozens of elderly Palestinians

in field executions after ordering them to leave their homes or after releasing

them from being detained without charges.

Western Officials Warn

of War-Crimes Complicity

More than 800 government officials

in the United States and Europe released a letter Friday criticizing their

countries’ leaders for providing unconditional military and diplomatic support

to Israel as it inflicts disaster on Gaza’s population.

[The 800-plus figure is ascribed to

an organizer of the letter who is quoted anonymously, for fear of reprisal, in

a report in The New York Times.]

The authors of the letter, who

remain anonymous, wrote that their attempts to voice concerns internally about

their governments’ support for Israel’s assault on Gaza “were overruled by

political and ideological considerations.”

“We are obliged to do everything in

our power on behalf of our countries and ourselves to not be complicit in one

of the worst human catastrophes of this century,” the letter reads. “We are

obliged to warn the publics of our countries, whom we serve, and to act in

concert with transnational colleagues.”

“Israel has shown no boundaries in

its military operations in Gaza, which has resulted in tens of thousands of

preventable civilian deaths,” the letter continues.

“There is a plausible risk that our

governments’ policies are contributing to grave violations of international

humanitarian law, war crimes, and even ethnic cleansing or genocide.”

The letter was coordinated by

government officials in The Netherlands, the U.S., and European Union bodies

and endorsed by civil servants in 10 countries, including Belgium, Denmark,

Finland, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

Josh Paul, a former U.S. State

Department official who resigned in October over the Biden administration’s

decision to continue arming Israel as it pummeled Gaza, called the new letter

“a remarkable statement from hundreds of individuals who have devoted their

lives to building a better world.”

“One-sided support for Israel’s

atrocities in Gaza, and a blindness to Palestinian humanity, is both a moral

failure, and, for the harm it does to Western interests around the globe, a

policy failure,” Paul told HuffPost.

“At a time where our politicians

seem to have forgotten them,” Paul added, the letter “is a much-needed reminder

of the core values that bind the transatlantic relationship, and a proof that

they endure.”

Paul told The New York Times that he

knew the organizers of the letter, which marks the latest sign of mounting

dissent inside Western governments over their support for Israel’s war on Gaza

as famine and disease spread across the enclave.

United Nations experts warned

earlier this week that Gazans are “enduring apocalyptic humanitarian

conditions, destruction, mass killing, wounding, and irreparable trauma.”

Berber van der Woude, a former Dutch

diplomat who resigned in 2022 over her government’s support for Israel’s

oppression of Palestinians, also spoke out in support of the new letter from

U.S. and European civil servants. Rights groups have accused the Dutch

government of complicity in Israeli war crimes, pointing to the export of

military supplies.

“Being a civil servant doesn’t

absolve you from your responsibility to keep on thinking,” van der Woude told

the Times on Friday. “When the system produces perverse decisions or actions,

we have a responsibility to stop it. It’s not as simple as ‘shut up and do what

you’re told’; we’re also paid to think.”

The unnamed officials implored their

governments to stop telling the public that “there is a strategic and

defensible rationale behind the Israeli operation and that supporting it is in

our countries’ interests.”

Israel claims it is targeting Hamas,

but one human rights monitor estimates that upwards of 90 percent of those

killed by Israeli forces in Gaza were civilians.

The Wall Street Journal reported

earlier this week that U.S. and Israeli officials believe that up to 80 percent

of Hamas’ tunnels are still intact after nearly four months of incessant

bombing, which has killed more than 27,000 Gazans.

To end the bloodshed, the civil

servants demanded that their governments “use all leverage available —

including a halt to military support — to secure a lasting cease-fire and full

humanitarian access in Gaza and a safe release of all hostages.”

They also urged world leaders to

“develop a strategy for lasting peace that includes a secure Palestinian state

and guarantees for Israel’s security, so that an attack like 7 October and an

offensive on Gaza never happen again.”

How the news cycle

misses the predominant violence in Israel-Palestine

The violence unfolding across

Palestine-Israel over the past four months has been accompanied by a

near-real-time deluge of information on social and news media worldwide. As

with other fast-moving, politically charged situations, a portion of that information

has been false, and fact checkers have had their hands full. And as on other

occasions, platforms such as Meta, Twitter/X, and even Telegram have been

criticized for not intervening, or for intervening in a biased way.

Humans, however, do not formulate

opinions based on information, but rather with stories spun from information —

and the relationship between them is far from linear. Fictitious information

can be arranged into a story that conveys profound truths, as great novelists

have proven for centuries. Conversely, and as the past several months of

coverage have demonstrated, there is no fact that cannot be indentured into the

service of a lie. Beyond disinformation (trafficking falsehoods), I worry as a

media researcher and longtime scholar of the Palestinian struggle that

decontextualization (selectively presenting truths) is the more ubiquitous and

elusive threat to our collective understanding.

Disinformation involves lying by

commission, such as by asserting that the 2020 U.S. presidential elections were

rigged against Trump, or that ivermectin cures COVID-19. Decontextualization,

on the other hand, is all about lying by omission, and psychologists have shown

that humans lie by omission with greater facility than by commission. Moreover,

omission’s signature characteristic is absence — something humans are

notoriously bad at noticing, which means we are liable to amplify

decontextualized narratives unwittingly.

For inveterate observers of

Israel-Palestine, though, the absences in the recent discourse have been

egregious. While much has been made of the differential coverage of Palestinian

versus Israeli suffering over the past several months, by far the greater

asymmetry is to be found when comparing coverage of the weeks of kinetic

violence after October 7 versus the decades of structural violence before.

The reason for this asymmetry runs

far deeper than political agendas. News networks cover bombings, shootings, and

other forms of kinetic violence because they are loud, finite events that seize

our attention, invite investigation and intrigue, and whose victims can be

counted, named, and mourned. By contrast, the everyday structural violence of

Israel’s occupation and apartheid is comparatively uneventful. Instead of loss,

it inflicts absence. Instead of killing, it simply aborts. Its first casualties

are dreams and destinies. Even its victims cannot offer a full accounting,

because how can you miss that of which you were always deprived?

Compared to kinetic violence, the

uneventful, continuous, and illegible nature of structural violence renders it

unfit for news coverage. Yet the two are inextricably linked. Decades of

structural violence give rise to weeks and months of kinetic violence. To cover

the latter while neglecting the former is, in a word, to decontextualize; to

show audiences the symptoms while depriving them of the underlying causes.

Without that context, audiences are more likely to see kinetic violence as

unprovoked, stemming from innate and intransigent ideological commitments that

necessitate a heavy-handed response.

In search of absence

All of the narratives spun by the

Israeli government to justify its murderous bombardment of the Gaza Strip —

including at the recent International Court of Justice hearing on the charge of

genocide — draw centrally on the facts of October 7: that Hamas-led militants

broke through the Gaza fence and, with intimate brutality, slaughtered over

1,100 people in southern Israel, most of them civilians, and took around 240

others hostage.

The narratives that “Hamas is ISIS,”

that Hamas is morally irredeemable and strategically irreconcilable, that

coexistence is impossible, that Hamas must be eradicated, that Palestinians in

Gaza themselves will be thankful for this — all of these dubious narratives are

lent authenticity by the undeniable horror of October 7. In this sense, these

are narratives not of disinformation, but decontextualization. And while there

have been some embellishments that have rightly drawn scrutiny, the core facts

about what happened on October 7 are true, withstand fact checking, and are

awful enough in their own right as to offer prima facie credibility to Israel’s

war narratives.

The deficiency of the Israeli

government’s narratives is not so much to be found in the information they

present, but rather in the information that is left absent. Countering

decontextualization is about seeing absence “with all its instruments” (to quote

Sinan Antoon’s translation of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish), seeing not

only what is presented but what is left out, and letting silences speak. As

Darwish would say, we must pull up some chairs for the ghosts.

The ghosts start to emerge when you

look at news media coverage in aggregate. MediaCloud, run by a consortium of

universities in the Boston area, has tracked news worldwide for over a decade.

Querying the MediaCloud database via their web interface, I found all news

articles published by American, Canadian, or British news outlets during 2023

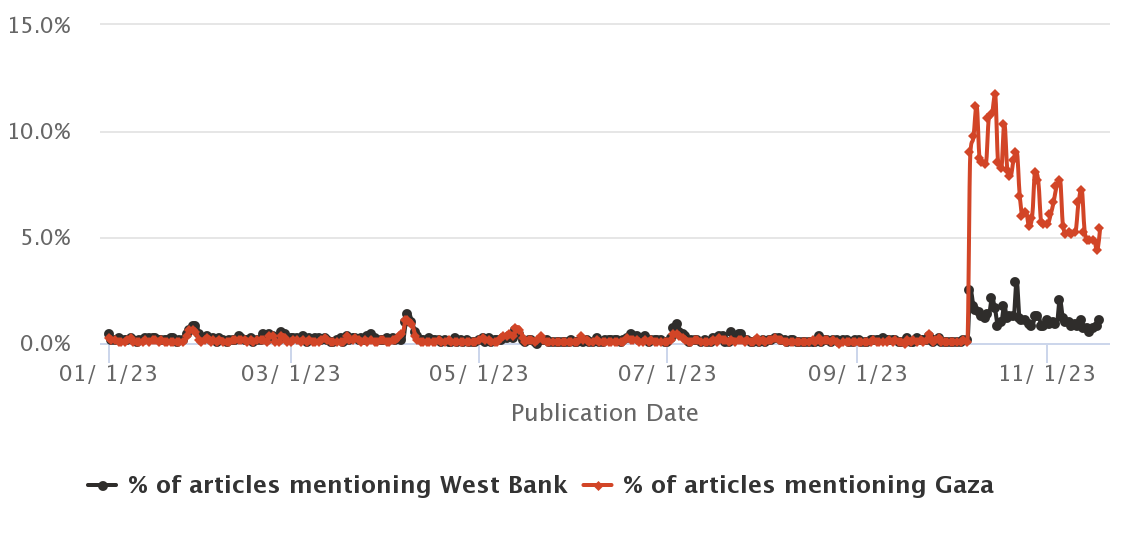

mentioning either “Gaza” or the “West Bank”, and generated the following chart.

Media coverage of

“Gaza” (red) and “West Bank” (black) in English-language news (US, UK, and

Canada) since the start of 2023. (MediaCloud)

In the chart, two curves are

depicted, one red and one black, representing the percentage of news articles

mentioning “Gaza” or “West Bank,” respectively, published on each day from the

start of 2023 to just before the temporary ceasefire in late November.

This chart suggests that the

occupied Palestinian territories are covered by the news when and where there

is kinetic violence — that is, bombing, shooting, stabbing, and so forth. Most

notably, the coverage of both Gaza and the West Bank after October 7 dwarfs

everything published in the comparatively stable nine months preceding it. The

coverage of Gaza after October 7, meanwhile, consistently exceeds that of the

West Bank, where kinetic violence was also happening but at orders of magnitude

below its sister territory.

I say kinetic violence for the sake

of distinguishing it from its complementary concept of structural violence.

Whereas bombings or shootings are examples of kinetic violence, structural

violence is exemplified by walls, barbed wire fences, or systems of

discriminatory laws. When a bomb goes off, it is a discrete event that can be

reported or remarked upon. Structures of violence, by contrast, are continuous

features that rend reality in two.

To get a glimpse of what it means

for Palestinians to be the victims of structural violence, we can turn to the

great Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, who once wrote that “our lives are

as a straight line that marches in shame and silence beside the line of our

destiny; but the two lie parallel, and shall never meet.” To live in the shadow

of a wall, or on the wrong side of a fence, or on the receiving end of a

discriminatory system, is to live “in the presence of absence,” to be haunted

by the ghost of one’s potential self — the person you would have become were it

not for this wall, this fence, this law, this structure. In Kanafani’s telling,

the life that Palestinians were meant to live haunts their every footstep. It

runs parallel, and in full view of their imagination, a daily reminder and

humiliation, next to which they trudge in silence and shame.

This is the agony of structural

violence with which Palestinians were living throughout 2023, and for the long

years and decades before that. But as the chart shows, news coverage only seems

to tune in when there are outbreaks of kinetic violence. Why does structural

violence get short shrift?

Firstly, structural violence is hard

to measure, even for scholars with the time, resources, and expertise to do so.

As Kanafani’s words suggest, structural violence can be measured by the gulf it

creates between one’s reality and potentiality; between one’s current life and

the life one could have lived were it not for this structure getting in the

way. Such counterfactual analysis, however, is slow, painstaking, and

statistical.

For example, using the West Bank as

Gaza’s counterfactual, scholars have estimated the economic and political costs

of the Gaza blockade since its imposition by Israel in 2007. While thoughtful,

these interventions are complicated, take years to produce, and invite

skepticism and disputation.

Even if you manage to measure

structural violence in a credible way, however, the findings ultimately come

off as overly statistical and hypothetical. Percentage-point declines in GDP or

employment simply lack the visceral horror of a suicide bomb or airstrike.

Behind those percentages are real people whose dreams have been crushed, and

who may succumb to depression, substance abuse, and death many years before

their natural time. But all of that is deemed so indirect, obscured, and

probabilistic that it just does not resonate with audiences as strongly.

Decontextualizing kinetic violence

For all of these reasons, structural

violence is a non-starter for news coverage. It is boring, expresses itself

through absences, non-events, things that did not happen, realities that were

not visited. News must sell itself to audiences, and audiences want to see

action and be diverted. Kinetic violence is attention-grabbing, and so (as the

chart above illustrates) it stands a greater chance of being covered in the

news.

Action-packed kinetic violence then

becomes the entirety of the story in our minds, through a defect of human

psychology that Israeli psychologist and Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman calls

the “WYSIATI principle”: what you see is all there is. Besides, in a world full

of events, who has time to think about what did not happen?

The asymmetry with which kinetic

violence is covered relative to structural violence has implications for how

international audiences perceive Palestine-Israel and other civil conflicts.

Though authorities may inflict structural violence on their subjects through a

system of oppression (colonialism, apartheid, military occupation, and so

forth), it is deemed not newsworthy, and receives only a modicum of coverage.

Eventually, after many years of

daily indignities and frustration, a breaking point is reached, and a rebellion

forms. The rebels are much weaker than the state, however, and cannot wield

structural violence. Instead, their primary tool is kinetic violence. And

because kinetic violence is newsworthy, the first time many outside observers

really pay attention to the conflict is when they see masked rebel gunmen

killing and terrorizing.

Indeed, if you analyze the patterns

of rocket fire and airstrikes over the Gaza Strip in the 2010s, you will find

over and over again that it is usually Palestinian militants who appear to

break the “calm.” And yet, buried in the confidential UN security reports from

which those findings were derived, nearly every rocket attack was preceded by

Israeli provocations — bulldozing orchards, revoking work permits, and so on —

that fell below the threshold of newsworthiness, and blended into the

day-to-day humdrum of structural violence.

Outside observers do not feel the

weight of the years and decades of structural violence that precede each moment

of kinetic violence. This is what it means for the latter to be

decontextualized: robbed of its structural provenance by human inattentiveness,

by our incapacity to see absence, and by the unwillingness of the media to

report what did not happen.

But the kinetic violence of October

7 cannot be understood without the structural violence of Oct. 6 and all the

days before. If you recklessly burn fossil fuels for decades, there will come a

time of hurricanes and wildfires. And if you indefinitely postpone the

political process of relieving structural violence, you risk outbreaks of

kinetic violence.

Hamas itself was founded 40 years

deep into the Nakba and the ensuing Palestinian refugee crisis, and 20 years

into the military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. It is the enraged

orphan of oppression, the product of a pattern so familiar to scholars of civil

conflict that it is astonishing we still bother with proper nouns. Think of it

as a law of conservation: violence is neither created nor destroyed, merely

converted from structural to kinetic.

That causal interplay, however, is

lost on most audiences. In the wake of October 7, activists and commentators

have heroically attempted to fill in the missing context extemporaneously, in

lengthy Twitter threads or on television in the fleeting moments offered to

them by news anchors. But a century of structural violence can scarcely be

recited let alone absorbed under such constraints, even as events on the ground

dramatically unfold.

The chart above shows, moreover,

that the half-life of coverage for a crisis even of this magnitude may only be

as little as six weeks. As the author John le Carré wrote, “history never stops

to take a breath,” and people’s attention moves on to the next item, and the

next.

For all of these reasons,

decontextualization is an enormous challenge to our understanding. To undo

decontextualization will require more than fact checking. We will need

econometrics and media observatories. We will need to read the works of

Palestinian novelists and Israeli psychologists. We will need compassion and

patience, and to reflect upon our own biases and blindspots. We will need all

these instruments to see absence.

The

only right that Palestinians have not been denied is the right to dream: The

Fifth Newsletter (2024)

Dear

friends,

Greetings

from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

On 26

January, the judges at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) found that it

is ‘plausible’ that Israel is committing a genocide against Palestinians in

Gaza. The ICJ called upon Israel to ‘take all measures within its power to

prevent the commission of all acts’ that violate the UN Convention on the

Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948). Although the ICJ did

not call explicitly for a ceasefire (as it did in 2022 when it ordered Russia

to ‘suspend [its] military operation’ in Ukraine), even a casual reading of

this order shows that to comply with the court’s ruling, Israel must end its

assault on Gaza. As part of its ‘provisional measures’, the ICJ called upon

Israel to respond to the court within a month and outline how it has implemented

the order.

Though

Israel has already rejected the ICJ’s findings, international pressure on Tel

Aviv is mounting. Algeria has asked the UN Security Council to enforce the

ICJ’s order while Indonesia and Slovenia have initiated separate proceedings at

the ICJ that will begin on 19 February to seek an advisory opinion on Israel’s

control of and policies on occupied Palestinian territories, pursuant to a UN

General Assembly resolution adopted in December 2022. In addition, Chile and

Mexico have called upon the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate

crimes committed in Gaza.

Israel’s

reaction to the ICJ’s order was characteristically dismissive. The country’s

national security minister, Itamar Ben Gvir, called the ICJ an ‘antisemitic

court’ and claimed that it ‘does not seek justice, but rather the persecution

of Jewish people’. Strangely, Ben Gvir accused the ICJ of being ‘silent during

the Holocaust’. The Holocaust conducted by the Nazi German regime and its

allies against European Jews, the Romani, homosexuals, and communists took

place between late 1941 and May 1945, when the Soviet Red Army liberated

prisoners from Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, and Stutthof. However, the ICJ was

established in June 1945, one month after the Holocaust ended, and began its

work in April 1946. Israel’s attempt to delegitimise the ICJ by saying that it

remained ‘silent during the Holocaust’ when it was, in fact, not yet in

existence, and then to use that false statement to call the ICJ an ‘antisemitic

court’ shows that Israel has no answer to the merits of the ICJ order.

Meanwhile,

the bombardment of Palestinians in Gaza continues. My friend Na’eem Jeenah,

director of the Afro-Middle East Centre in Johannesburg, South Africa, has been

reviewing the data from various government ministries in Gaza as well as media

reports to circulate a daily information card on the situation. The card from

26 January, the date of the ICJ order and the 112th day of the genocide,

details that over 26,000 Palestinians, at least 11,000 of them children, have

been killed since 7 October; 8,000 are missing; close to 69,000 have been

injured; and almost all of Gaza’s 2.3 million residents have been displaced.

The numbers are bewildering. During this period, Israel has damaged 394 schools

and colleges, destroying 99 of them as well as 30 hospitals and killing at

least 337 medical personnel. This is the reality that occasioned the genocide

case at the ICJ and the court’s provisional measures, with one judge, Dalveer

Bhandari of India, going further to say plainly that ‘all fighting and

hostilities [must] come to an immediate halt’.

Amongst

the dead are many of Palestine’s painters, poets, writers, and sculptors. One

of the striking features of Palestinian life over the past 76 years since the

Nakba (‘Catastrophe’) of 1948 has been the ongoing richness of Palestinian

cultural production. A brisk walk down any of the streets of Jenin or Gaza City

reveals the ubiquity of studios and galleries, places where Palestinians insist

upon their right to dream. In late 1974, the South African militant and artist

Barry Vincent Feinberg published an article in the Afro-Asian journal Lotus

that opens with an interaction in London between Feinberg and a ‘young

Palestinian poet’. Feinberg was curious why, in Lotus, ‘an unusually large

number of poems stem from Palestinian poets’. The young poet, amused by

Feinberg’s observation, replied: ‘The only thing my people have never been

denied is the right to dream’.

Malak

Mattar, born in December 1999, is a young Palestinian artist who refuses to

stop dreaming. Malak was fourteen when Israel conducted its Operation

Protective Edge (2014) in Gaza, killing over two thousand Palestinian civilians

in just over one month—a ghastly toll that built upon the bombardment of the

Occupied Palestinian Territory that has been ongoing for more than a

generation. Malak’s mother urged her to paint as an antidote to the trauma of

the occupation. Malak’s parents are both refugees: her father is from al-Jorah

(now called Ashkelon) and her mother is from al-Batani al-Sharqi, one of the

Palestinian villages along the edge of what is now called the Gaza Strip. On 25

November 1948, the newly formed Israeli government passed Order Number 40,

which authorised Israeli troops to expel Palestinians from villages such as

al-Batani al-Sharqi. ‘Your role is to expel the Arab refugees from these

villages and prevent their return by destroying the villages… Burn the villages

and demolish the stone houses’, wrote the Israeli commanders.

Malak’s

parents carry these memories, but despite the ongoing occupation and war, they

try to endow their children with dreams and hope. Malak picked up a paint brush

and began to envision a luminous world of bright colours and Palestinian

imagery, including the symbol of sumud (‘steadfastness’): the olive tree. Since

she was a teenager, Malak has painted young girls and women, often with babies

and doves, though, as she told the writer Indlieb Farazi Saber, the women’s

heads are often titled to the side. That is because, she said, ‘If you stand

straight, upright, it shows you are stable, but with a head tilted to one side,

it evokes a feeling of being broken, a weakness. We are humans, living through

wars, through brutal moments… the endurance sometimes slips’.

Malak

and I have corresponded throughout this violence, her fears manifest, her

strength remarkable. In January, she wrote, ‘I’m working on a massive painting

depicting many aspects of the genocide’. On a five-metre canvas, Malak created

a work of art that began to resemble Pablo Picasso’s celebrated Guernica

(1937), which he painted to commemorate a massacre by fascist Spain against a

town in the Basque region. In 2022, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency

for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) published a profile on Malak,

calling her ‘Palestine’s Picasso’. In the article, Malak said, ‘I was so

inspired by Picasso that, in the beginning of my art journey, I tried to paint

like him’. This new painting by Malak reflects the heartbreak and steadfastness

of the Palestinian people. It is an indictment of Israel’s genocide and an

affirmation of Palestinians’ right to dream. If you look at it closely, you

will see the victims of the genocide: the medical workers, the journalists, and

the poets; the mosques and the churches; the unburied bodies, the naked

prisoners, and the corpses of small children; the bombed cars and the fleeing

refugees. There is a kite flying in the sky, a symbol from Refaat Alareer’s

poem ‘If I Must Die’ (‘you must live to tell my story… so that a child,

somewhere in Gaza while looking heaven in the eye… sees the kite, my kite you

made, flying up above and thinks there is an angel there bringing back love’).

Malak’s

work is rooted in Palestinian traditions of painting, inspired by a history

that dates back to Arab Christian iconography (a tradition that was developed

by Yusuf al-Halabi of Aleppo in the seventeenth century). That ‘Aleppo Style’,

as the art critic Kamal Boullata wrote in Istihdar al-Makan, developed into the

‘Jerusalem Style’, which brightened the iconography by introducing flora and

fauna from Islamic miniatures and embroidery. When I first saw Malak’s work, I

thought of how fitting it was that she had redeemed the life of Zulfa al-Sa’di

(1905—1988), one of the most important painters of her time, who painted

Palestinian political and cultural heroes. Al-Sa’di stopped painting after she

was forced to flee Jerusalem during the 1948 Nakba; her only paintings that

remain are those that she carried with her on horseback. Sa’di spent the rest

of her life teaching art to Palestinian children at an UNRWA school in

Damascus. It was in one such UNRWA school that Malak learned to paint. Malak

seemed to pick up al-Sa’di’s brushes and paint for her.

It is

no surprise that Israel has targeted UNRWA, successfully encouraging several

key Global North governments to stop funding the agency, which was established

by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 302 in 1949 to ‘carry out direct

relief and works programmes for Palestine refugees’. In any given year, half a

million Palestinian children like Malak study at UNRWA schools. Raja Khalidi,

director-general of the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS),

says of this funding suspension: ‘Given the long-standing precarious nature of

UNRWA’s finances… and in light of its essential role in providing vital

services to Palestine refugees and some 1.8 million displaced persons in Gaza,

cutting its funding at such a moment heightens the threat to life against

Palestinians already at risk of genocide’.

I

encourage you to circulate Malak’s mural, to recreate it on walls and public

spaces across the world. Let it penetrate into the souls of those who refuse to

see the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people.

Warmly,

Vijay

Palestinian

Babies Aren’t All That Innocent

A Republican

representative believes that Palestinian babies are not innocent civilians but

“terrorists” who should be killed.

Florida

Representative Brian Mast made the horrifying comment when confronted by Code

Pink protesters outside his office on Wednesday.

In a video, Mast

can be seen calmly telling the demonstrators, “It would be better if you kill

all the terrorists and kill everyone who are supporters.”

When asked if he

has seen the images of Palestinian babies killed in Israeli attacks, Mast says,

“These are not innocent Palestinian civilians.”

“The babies?”

the activists asks in astonishment.

Mast then says

that the “half a million people starving to death” should have elected a

pro-Israel government.

When one

protester points out that much of Gaza’s infrastructure has been destroyed,

Mast says, “And there’s more infrastructure that needs to be destroyed.”

“Did you not

hear me? There’s more that needs to be destroyed,” he says again for emphasis.

More than 27,000

Palestinians have been killed since October in Israel’s constant bombardment of

Gaza. The majority of the victims have been women and children.

Mast’s horrific

comments—and the chilling way in which he delivered them—should come as no

surprise. In November, just a few weeks after the war began, Mast compared

Palestinian civilians to Nazis and implied that they are all guilty for Hamas’s

atrocities.

“I would

encourage the other side to not so lightly throw around the idea of ‘innocent

Palestinian civilians,’ as is frequently said,” he said on the House floor.

“I don’t think

we would so lightly throw around the term ‘innocent Nazi civilians’ during

World War II.”

No comments:

Post a Comment