July 26, 2024

HONG KONG – The

Beijing Declaration, signed earlier this week, constitutes yet another stunning

Chinese diplomatic coup, but the document goes far beyond affirming China’s

pull.

The gathering of

representatives of 14 Palestinian factions to commit to full reconciliation

showed the entire world that the road to solving intractable geopolitical

problems is no longer unilateral: it is multipolar, multi-nodal, and features

BRICS/Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member China as an inescapable

leader.

The concept of

China as a peacemaking superpower is now so established that after the

Iran–Saudi Arabia rapprochement and the signing of the Beijing Declaration,

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba chose to tell his Chinese counterpart

Wang Yi in Beijing that Kiev is now finally ready to negotiate the end of the

NATO–Russia proxy war in Ukraine.

Palestinians who

came to Beijing were beaming. For Fatah Vice Chairman Mahmoud al-Aloul, “China

is a light. China’s efforts are rare on the international stage.”

Hamas spokesman

Hussam Badran said the Palestinian resistance movement accepted the Chinese

invitation “with a positive spirit and patriotic responsibility.” All

Palestinian factions have reached a consensus on “Palestinian demands to end

the war,” adding that the “most important” part of the declaration is to form a

government that builds Palestinian national consensus to “manage the affairs of

the people of Gaza and the West Bank, oversee reconstruction, and create

conditions for elections.”

The “three-step”

Chinese proposal

Wang Yi cut to

the chase: the Palestinian issue, says the Chinese foreign minister, is at the

core of everything in West Asia. He emphasized that Beijing:

“ … has never had any selfish interests in

the Palestinian issue. China is one of the first countries to recognize the PLO

[Palestine Liberation Organization] and the State of Palestine and has always

firmly supported the Palestinian people in restoring their legitimate national

rights. What we value is morality and what we advocate is justice.”

What Wang did

not say – and didn’t need to – is that this position is the overwhelming BRICS+

position, shared by the Global Majority, including, crucially, all Muslim

countries.

It’s all in a

name – everyone in the foreseeable future will note this is the “Beijing”

declaration unequivocally supporting One Palestine.

No wonder all

political factions had to rise to the occasion, committing to support an

independent Palestinian government with executive powers over Gaza and the

occupied West Bank. But there’s a catch: this will take place immediately after

the war, which the regime in Tel Aviv wants to prolong indefinitely.

What Wang Yi

left somewhat implicit is that China’s consistent historical position

supporting Palestine may be a decisive factor in helping future Palestinian

governance institutions. Beijing is proposing three steps to get there:

First, a

“comprehensive, lasting and sustainable” ceasefire in Gaza as soon as possible,

and “access to humanitarian aid and rescue on the ground.”

Second, “joint

efforts” – assuming western involvement – toward “post-conflict governance of

Gaza under the principle of ‘Palestinians governing Palestine.’” An urgent

priority is restarting reconstruction “as soon as possible.” Beijing stresses

that “the international community needs to support Palestinian factions in

establishing an interim national consensus government and realize effective

management of Gaza and the West Bank.”

Third, help

Palestine “to become a full member state of the UN” and implement the two-state

solution. Beijing maintains that “it is important to support the convening of a

broad-based, more authoritative, and more effective international peace

conference to work out a timetable and road map for the two-state solution.”

For all the

lofty aims, especially when it is patently clear that Israel has de facto

buried the two-state solution – as witnessed in the Knesset’s recent vote to

reject any Palestinian state – at least China is directly proposing what the

Global Majority unanimously considers as a fair outcome.

Also important

to note is the presence of diplomats from China’s fellow BRICS members Russia,

South Africa, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, alongside diplomats from Algeria, Qatar,

Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Turkiye at the signing of the declaration.

Genocide as a

wellness treatment

Now compare

China’s diplomatic coup with the US Congress giving 58 standing ovations to

Israel’s psychopath-in-chief peddling the notion of genocide as a wellness

treatment.

Bibi Netanyahu’s

hero’s welcome in Washington takes the notion of collective psychopathology to

new heights. And yet complicity in the Gaza genocide is not exactly an

exception to the rule when it comes to American political leadership.

The Hegemon’s

political “elites” – with Franco-British help – have also been active

collaborators and weaponizers of the oppressive Saudi and Emirati bombing and

blockade of Yemen, which, over nine years, collectively caused even more

civilian deaths than in Gaza. Famine in Yemen is far from over, yet this has

been a completely invisible war to the collective west.

At least karma

ended up intervening. China promoted the rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and

Iran, and Riyadh has become a BRICS+ member and deeply engaged in the

de-dollarization drive, in which the petroyuan is emerging.

Moreover, the

Yemeni resistance movement Ansarallah managed to single-handedly humiliate the

US Navy. The US–UK “revenge” was to open another war front, bombing Yemeni

installations to protect Israeli shipping in the Red Sea and waterways beyond.

As much as Yemen

remains at war on two fronts – against the Hegemon and Israel while keeping an

eye on potential Saudi shenanigans – Palestine continues to be decimated by a

fully US-backed Israel. The Beijing Declaration will not mean anything if not

implemented. But how?

Assuming a

partial success, the declaration may be able to put a spanner in the works of

the absolute impunity of the Tel Aviv–Washington agenda because after the

Beijing deal, finding a collaborator Palestine government to perpetuate the

occupation could be much more difficult.

All Palestinian

factions now owe China a serious debt; internal squabbling will have to cease.

Otherwise, it would amount to a serious loss of face for Beijing.

At the same

time, the Chinese leadership seems very much aware that this bet is a Global

South bet – laying bare the Hegemon’s hypocrisy for the whole world to see.

Much like the Saudi–Iran deal clinched in Beijing, the optics could not be more

auspicious, especially when compared to the Israeli–American refusal of a

meaningful ceasefire.

Real Palestine

unity will also give extra bite to each and every global initiative at the UN,

the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and other global forums.

All of the

above, though, pales in comparison to the dire facts on the ground. The

ideologically genocidal Israelis – fully supported by US political “leadership”

– continue to get away with what they really want: the outright mass

murder-cum-ethnic cleansing of millions of Palestinians, something that, in

theory, should lead to an absolute demographic majority for Israel’s expansion

into all Palestinian lands.

This tragedy

will not stop anytime soon. The Beijing Declaration won’t make it stop. Only

the Hegemon severing its weapons funnel to Tel Aviv can force it to stop. Yet

today, what we’re instead seeing from Washington is 58 standing ovations for

genocide.

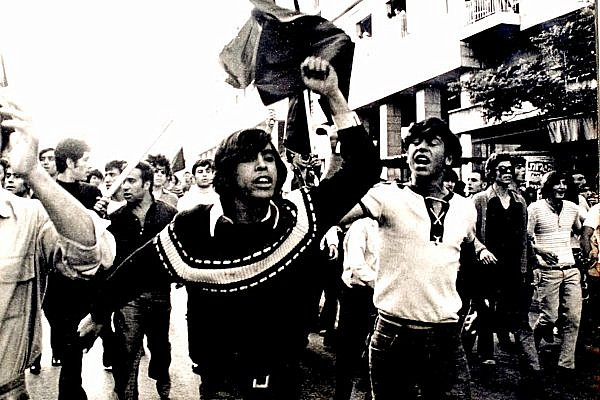

Ben Reiff

A Black Panther protest in Jerusalem 1971

In January 1971, a short news report

appeared on the back page of the left-leaning Israeli newspaper, Al Hamishmar.

The editors evidently didn’t think much of the story, but its publication

caused an immediate sensation. The headline, a quote from one of the article’s

subjects, foretold the emergence of a revolutionary new movement from

Jerusalem’s Musrara neighborhood that would set off a political earthquake on

Israel’s streets — one whose aftershocks can still be felt today. “We want to

organize against the Ashkenazi government and establishment,” it read. “We will

become the Black Panthers of the State of Israel.”

The adopted name was deliberately

provocative. The Israeli media had regularly vilified the original Black

Panther Party in the United States — a militant Black power organization

founded some five years earlier in Oakland, California — as antisemitic for

denouncing Israel as an imperialist state and expressing solidarity with the

Palestinian liberation movement. But the Israeli Panthers’ identification with

their American counterparts went beyond merely borrowing their name: in the

Black struggle against racism, poverty, and police brutality, the Jerusalem

youths saw their own experience reflected back at them.

In today’s terms, the Israeli

Panthers were not actually Black; they were the sons and daughters of the

Jewish exodus from the Arab world, known nowadays as Mizrahi Jews (plural:

Mizrahim), but more commonly referred to at the time as Sephardim. These Jews

arrived in their hundreds of thousands to a fledgling Israeli state in the

early 1950s. But they soon found themselves being racialized as “Black” by a

hegemonic Ashkenazi class, tracing its heritage to Europe, whose vision of a

Jewish state had not much accounted for Mizrahim before the Holocaust

eliminated two-thirds of European Jewry.

Israel’s Ashkenazi founders —

including David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister — greeted the Mizrahi

arrivals with an abundance of racist disdain. The authorities hosed them down

with pesticide; settled them in remote desert camps or crammed them into the

homes of exiled Palestinian refugees (such as those in Musrara);

proletarianized them and funneled them into menial labor; suppressed their

culture; separated thousands of them from their children; and forced tens of

thousands to undergo unsafe radiation treatment that led to serious health

complications. All the while, a rebellion was brewing.

When a group of impoverished Mizrahi

youths announced the establishment of their movement and declared a revolt

against the system, local and international reporters flocked to interview

them. Within weeks, the Panthers counted hundreds, if not thousands, among

their ranks, and led a series of escalating protests and direct actions

designed to make it impossible for the Israeli authorities to ignore them. They

demanded that the state channel its resources toward addressing the stark

social problems that plagued Mizrahim, pulling back the curtain on Israel’s

supposedly socialist ethos.

Saadia

Marciano photographed on Jerusalem's Jaffa Street, 1971. (Meir Wigoder)

The authorities, however, denied

that any such problems existed, and instead sought to suppress the Panthers’

struggle. Police violently cracked down on the protests, and infiltrated the

organization with a mole who would feed them information for years — and who

was almost accidentally elected the group’s leader, before convincing them to

choose somebody else.

Golda Meir, the prime minister at

the time, saw the Panthers primarily as a public relations issue, fearing that

their activities could give Israel and Zionism a bad name abroad and discourage

Jews in the diaspora from immigrating. “I want to get it out of your heads that

you have brought a revolution to the country,” she told a group of Panther

leaders with whom she agreed to meet in April 1971, after they had initiated a

hunger strike in front of the Western Wall. Echoing her infamous denial of the

existence of a Palestinian people, she insisted: “There is no issue of

Ashkenazim and Sephardim here.”

A month later, the Panthers

mobilized thousands to a demonstration in downtown Jerusalem, which ended with

protesters hurling glass bottles, bricks, rocks, and even Molotov cocktails at

police. Immortalized as “The Night of the Panthers,” it was the largest civil

disturbance that the Israeli authorities would face until a mass uprising of

Palestinian citizens of the state five years later, which has been commemorated

every year since as Land Day.

A contested legacy

Despite their seismic entrance into

Israeli history, half a century later, the Panthers and their rebellion have

been largely — and perhaps wilfully — forgotten. Their memory is primarily kept

alive only by a few surviving Panthers, a handful of dedicated archivists and

historians, the Mizrahi left in Israel and abroad, and parts of the broader

Israeli radical left. But the Panthers’ relevance, argues Israeli-American

journalist Asaf Elia-Shalev in a meticulous new book, is enduring.

“I was captivated,” Elia-Shalev

writes in the preface, “by how a group of kids with criminal records and a

provocative name helped redirect the course of the national conversation and

forced Israel to face issues it had been denying. What I was slowly learning

about the Panthers seemed deeply consequential, and in their forgotten story, I

saw the roots of the country that Israel has become.”

“Israel’s Black Panthers: The

Radicals Who Punctured a Nation’s Founding Myth” is the first English book to

deal exclusively and comprehensively with this turbulent chapter of history. It

was born out of an encounter that the author had about a decade ago with one of

the Panthers’ central figures, Reuven Abergel.

“Israel’s

Black Panthers: The Radicals Who Punctured a Nation's Founding Myth,” by Asaf

Elia-Shalev, University of California Press, 2024.

“I went on a tour of Musrara that

Reuven led, and my mind was just blown by this guy,” Elia-Shalev recalled in an

interview with +972. “He was around 70 years old at the time, and he had this

fire and sense of urgency, and spoke so compellingly about his life. I had just

read the autobiography of Malcolm X, and Reuven sounded like him in lots of

ways; he was saying such powerful things. So I thought, how come no one has

heard this story?”

Over the next several years,

Elia-Shalev would record some 50 hours of interviews with Abergel, which

eventually became the foundation of the book. Abergel does not speak English,

and he told Elia-Shalev — who is himself the grandchild of Mizrahim who immigrated

to Israel from Iraq — that telling his story to an American journalist in

Hebrew felt like “smuggling a letter out of prison.”

Though the author would go on to

interview dozens more Panthers, Abergel’s recollections were crucial because he

was the only one among the group’s leadership cadre who had not yet passed away

or lost his full faculties. “Saadia Marciano died long before I got started,”

Elia-Shalev said. “Charlie Biton, when I got to him, was very sick and unable

to sit down for interviews with me for very long, and the same with Kochavi

Shemesh” — both of whom have since also died.

Elia-Shalev concedes that, given the

ideological and personal fissures that later plagued the Panthers, the emphasis

on Reuven’s point of view risks privileging a certain perspective on events.

But he mitigated this by scouring archives, old news articles, and a previously

classified Israeli police intelligence file to find everything he could on the

Panthers’ activities, how they were received, and the authorities’ attempts to

repress them.

“There are battles over the legacy

of the Panthers,” Elia-Shalev explained. “I did my best to be faithful to the

facts, but I’m also limited by the materials available and the people that are

still around. Reuven is someone who has spent the last decades of his life,

long after the Panthers, involved in virtually every social justice struggle in

Israel. And that has definitely given him a lot of credibility to speak on the

Panthers [while] others have died or didn’t remain involved in activism.”

Indeed, in recent years, Abergel has

been a regular fixture at protests against Israel’s occupation of the

Palestinian territories, the cost of living in the country, and government

plans to deport asylum seekers. But he reflects back on what became of the

Panthers’ revolt somewhat wistfully, telling Elia-Shalev: “In every revolution,

the dreamers sow the seeds, the courageous carry it forward, and the bastards

reap the fruits of the struggle.”

Israeli

Black Panther Reuven Abergil addressed a crowd at the Levinksy Park protest

camp in south Tel Aviv, July 26, 2011. (Oren Ziv/Activestills.org)

Rebelling to belong

The Panthers were hardly the first

Mizrahim to challenge the racism and discrimination they faced in Israel.

Initially, resistance took the form of new arrivals urging friends and

relatives outside Israel to defy the Zionist emissaries encouraging them to

immigrate; some of the letters never reached their intended recipients because

the Israeli government’s Censorship Bureau confiscated them, deeming them a

national security risk.

By mid-1949, Mizrahim had already

begun demonstrating at government buildings across the country to demand better

housing, jobs, and food provisions. Protests continued to spring up throughout

the 1950s in ma’abarot (tent camps for new immigrants) and the development

towns that replaced them, which the police promptly suppressed.

In 1959, a police officer shot a

Mizrahi resident of Haifa’s Wadi Salib neighborhood — where the state had

densely settled Mizrahim in Palestinian homes confiscated after the Nakba —

leading hundreds to flood the streets in fury. Under the leadership of the

Union of North African Immigrants, the protesters called for the elimination of

the ma’abarot and urban slums, and demanded quality education for all citizens.

The authorities eventually quelled

the rebellion, which had spontaneously spread to other Mizrahi localities as

well. A government commission of inquiry into the events insisted that Mizrahim

in Israel do not face discrimination on the basis of their ethnicity.

More than a decade later, however,

even with their share among Israel’s Jewish population being roughly equal, the

socioeconomic gaps between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim remained stark. This was

perhaps most apparent in the education system, where a majority of Mizrahi

adolescents were not in school, while Ashkenazim comprised about 99 percent of

university students.

Israeli

Black Panthers, including Charlie Biton, protesting on Dizengoff Street in Tel

Aviv, May 1, 1973. (Moshe Milner/GPO)

What distinguished the Panthers from

those who preceded them, though, was the extent to which the Israeli

establishment viewed the organization as a threat. As if to emphasize that

danger, the police and media initially sought to portray the Panthers as being

in league with the anti-Zionists of Matzpen — a Marxist group largely made up

of middle-class Ashkenazim — which the Israeli media had spent much of the past

decade demonizing.

“There was this racist urge to say

that these young Mizrahi men couldn’t possibly be organizing of their own

accord, and they must be puppets on a string,” Elia-Shalev told +972. While

Matzpen offered some support to the Panthers — such as by printing flyers and

T-shirts for their protests, and amplifying their struggle in Matzpen’s journal

— the Panthers were wary of allowing too much room for external influence over

their activities. At one meeting where Ashkenazi activists were felt to have

overstepped the mark, Elia-Shalev explained, “Reuven and his brothers

physically kicked them out.”

The Panthers’ relationship to

Zionism, meanwhile, was much less clear-cut. Throughout the book, the reader

can discern a constant tension between the Panthers’ repudiation of the Israeli

regime and their apparent desire to be welcomed into it as equal partners. From

action to action, and perhaps from activist to activist, the group seems to

have oscillated between these two tendencies.

On the one hand, the Panthers’

backing for a Palestinian state put them firmly at odds with all but the

tiniest minority of Israeli Jews at the time. On multiple occasions between

1973 and 1980, representatives of the Panthers contravened Israeli law by meeting

with, or trying to meet with, Yasser Arafat and other figures in the Palestine

Liberation Organization (PLO), which at the time was committed to armed

struggle in pursuit of liberation.

Moreover, at demonstrations,

Panthers frequently chanted “Less for the Phantoms” — the name of the fighter

jets that the United States sold to Israel — “and more for the Panthers.” And

to protest what they saw as the state’s hypocritical support for the liberation

of Soviet Jewry while Mizrahim languished in poverty in Israel, they tried to

disrupt the 1972 World Zionist Congress.

A

Black Panthers protest in Jerusalem, 1971. (Yosef Hochman, courtesy of the Yad

Yaari Research and Documentation Center)

But the Panthers’ rebuke of core

Zionist tenets only went so far. The flyers for their first official

demonstration ended with the sentence: “We will demonstrate for our right to be

like all the other citizens in this country.” Another rally ended with the

singing of the Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem. And in their meeting with

Golda Meir, Abergel — who only later became avowedly anti-Zionist — assured the

prime minister that the Panthers are “devoted to our country, and patriotic,

and we love it.”

For Elia-Shalev, this ambivalence is

one of the main differences between the Israeli Panthers and their U.S.

counterparts. “The American Black Panthers were real ideologues, real

revolutionaries, who wanted to join with the oppressed people of the world and

create a new order,” he said. “The [Israeli] Panthers weren’t quite there. In

my view, they talked a big game, used phrases like ‘by any means necessary,’

and threatened to overthrow the state, but I think they ultimately wanted to

belong.

“They saw the Palestinian struggle

as a legitimate one, and they defined Mizrahim as a potential bridge to the

Arab world,” he continued. “But fundamentally, they thought it was wrong that

the Jewish state would marginalize more than half of its Jewish population.

They were hurt that they were denied an opportunity to belong to society and

the state, and were willing to at least threaten to overthrow it in order to

get a seat at the table. Whatever Zionism is or was, it wasn’t serving

Mizrahim, and so the Panthers came out against the people who represented it.”

An avenue into power

In March 1972, the Panthers carried

out one of the stunts for which they are most widely remembered: “Operation

Milk,” in which they stole milk bottles from the doorsteps of Jerusalem’s

wealthiest neighborhoods and delivered it to the poor, for whom fresh milk was

vastly unaffordable. Support for the Panthers was growing; one survey in

mid-1971 put it at around 40 percent among Jewish Israelis. And it was having a

tangible impact: the state budget for 1972 — which has been retrospectively

labeled “The Budget of the Panthers” — saw substantial funding diverted from

defense spending to housing, welfare, and education.

The organization was also gaining

prominence abroad. In September 1971, the New York Times ran a cover story on

them. Left-wing radicals from Europe scrambled to meet them, and Panther

leaders took up invitations to attend political summits around the world.

Israeli Black Panthers

take part in a May Day demonstration in Tel Aviv, May 1, 1973. (Moshe Milner)

Before long, and in spite of some

fairly acrimonious infighting, the Panthers sought to translate their soaring

popularity into political power. A significant showing for the movement in the

ballot for the Histadrut — Israel’s quasi-governmental national labor union,

which was dominated by the Labor Party — in September 1973 raised hopes that

they could bring about a major upheaval in the upcoming Knesset election,

scheduled for late October 1973. They campaigned on a platform that called for

universal health insurance, increased welfare support, and the freeing of all

prisoners.

But three weeks before the polls, on

Oct. 6, Syria and Egypt launched an attack that caught Israel completely off

guard, marking the start of the Yom Kippur War. The election was postponed, and

by the time it eventually took place on Dec. 31 — after the nation had buried

over 2,500 troops — the public’s attention was focused squarely on issues of

national security. The Panthers’ momentum, built up over the span of nearly two

years, had completely fizzled, and they failed to cross the minimum vote threshold

required to enter the Knesset.

Over the next few years, the

Panthers would try to regroup and recover from their electoral defeat. But the

mood inside the country had changed dramatically, and there was little interest

in “social” issues anymore. By the time the next election came around four

years later, a series of splits meant that the Panthers were represented across

four different lists. Two of the leadership cadre entered the Knesset — Charlie

Biton, with the Arab-Jewish party Hadash, and Saadia Marciano, with the Left

Camp of Israel (Sheli) — where they went on to promote the Panthers’ cause

inside the corridors of power.

But most of the Panthers’

traditional base didn’t vote for either of these leftist parties. Instead, in

what’s remembered as the “Ballot Rebellion” of 1977, they opted en masse for

the right-wing Likud party of Menachem Begin, an Ashkenazi populist who courted

Mizrahim disaffected with decades of Labor hegemony while attacking Meir’s

government for its security failures. Nearly half a century later, it is Likud

— and Begin’s eventual successor as party leader, Benjamin Netanyahu — that

reigns supreme in Israeli politics, thanks in no small part to a loyal base of

Mizrahim.

“If we want to understand how

Netanyahu maintains power, and where the alliance comes from between a large

chunk of the Mizrahi public and the Likud party, the Panthers help us

understand how we got there — even if the causation is a little complicated,”

Elia-Shalev explains. “The Panthers brought to the surface not just the squalid

conditions that [Mizrahim] were living in, but also the injustice of it, and

they told people who to blame: the Labor-dominated Israeli government.

“By attacking the old order over and

over again, they freed people to rebel and to seek an avenue into power and

belonging,” he continued. “The Mizrahi public by and large didn’t follow the

Panthers after they unleashed this rebellion. The person who was able to

capitalize on the energy was Menachem Begin, who said [to Mizrahim]: ‘I’m

offering you a place on center stage. You’re the real Jews, the real warriors

of this country. Come, join me.’ That was very appealing, and it worked.”

Unresolved grievances

With Mizrahi assent to Likud

hegemony, the socioeconomic chasm between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim that

characterized the era of Labor rule has certainly narrowed over the past five

decades, even if concrete data remains hard to come by. Mizrahi culture flourishes

in Israel today, and the authorities have taken concrete steps toward

recognizing some past injustices.

Yet vast inequalities still remain.

Albeit to a far lesser extent than Palestinian citizens of Israel, Mizrahim are

effectively barred from accessing or living in certain parts of the country due

to racist laws and practices emanating largely from the Zionist left. They are

underrepresented in fields such as media, academia, law, and politics. There

has never been a Mizrahi prime minister, and only a handful of Mizrahim have

been appointed to the most highly coveted government ministries.

The army, too, reflects Israel’s

enduring ethnic-class divide, with Ashkenazim commonly chosen for command

positions and intelligence units; Mizrahim, on the other hand, are more likely

to be the cannon fodder for combat units — even as they have increasingly begun

to assert their power from below. And after enduring tortuous legal struggles

for housing rights, Mizrahim continue to be evicted from the very homes that

the state settled them in three generations earlier. The “bastards who reaped

the fruits of the struggle,” as Abergel put it, have failed to bring about the

profound changes that the Panthers envisioned.

Members

of the Israeli Black Panthers disrupt the opening session of the World Congress

of North African Immigrants in Tel Aviv, October 25, 1975. (Ya’acov Sa’ar)

By the 1980s, many Mizrahim had

already grown disillusioned by Likud’s inability to turn its rhetoric into

material action, and found a home in new religious Mizrahi parties: first Tami,

which gained three MKs in the 1981 election, and then Shas, which has grown

since 1984 to become a major force in Israeli politics. Rather than continuing

where the Panthers left off, however, critics have characterized Shas as merely

“the state’s subcontractor for welfare services to the needy.” More recently,

growing numbers of Mizrahim have found a home on the radical right, with

Israel’s National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, who is of Mizrahi heritage

himself, succeeding where his idol Meir Kahane failed.

None of this has stopped Likud and

Netanyahu from continuing to present themselves as saviors of the Mizrahim and

the champions of the downtrodden masses — even invoking the memory of the

Panthers in doing so. “It’s interesting to see nostalgia for the Panthers on

the Israeli right, Elia-Shalev remarked. “You’d never see the Republican Party

being nostalgic for the Black Panther Party of Oakland. But Likud has very

effectively tapped into Mizrahi grievances, and they obscure the fact that the

Panthers were a distinctly left-wing group, with a very radical program that

called for a socialist economy and recognition of a Palestinian state.”

Nonetheless, Elia-Shalev is not

convinced that the bond between Mizrahim and the right is unbreakable,

especially in the wake of October 7 and Netanyahu’s desperate attempts to cling

to power as his public support wanes. “I think Israel is going through a

paradigm shift right now — similar to the shift that followed the 1973 War,

which ultimately led to the downfall of Labor and the rise of Likud,” he said.

“It might not happen tomorrow; it

could take a few years like it did after 1973. But I think we’re going to see

the downfall of Likud and the rise of something else,” Elia-Shalev continued.

And the legacy of the Panthers suggests, if the Israeli political map is

redrawn, that an alternative Mizrahi political vision is still possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment