Laura Baisas

On a hot and

humid Florida night in late August 1859, the sky suddenly lit up. But it was

not from fireflies or a fireswamp. Instead, it was the Northern Lights–or

aurora borealis. The aurora is usually seen in far more northern latitudes, but

it had somehow reached the subtropics and danced across the night sky. Reports

of the aurora came in from as far south as Central America and some in the

Rocky Mountains even believed it was morning because the sky was so bright.

Across the

Atlantic Ocean in England, a wealthy amateur astronomer named Richard

Carrington was also watching the cosmos. However, Carringon had his eyes on the

Sun and its various sunspots and solar flares.

“Sunspots are

there all the time, almost. You can see them with a small telescope,”

University of Glasgow astrophysicist Hugh Hudson tells Popular Science.

“Carrington was sketching the spots’ areas and recording them. He noticed at a

certain point that there were two bright patches of light that appeared in the

sunspot group, which ought not to have been there.”

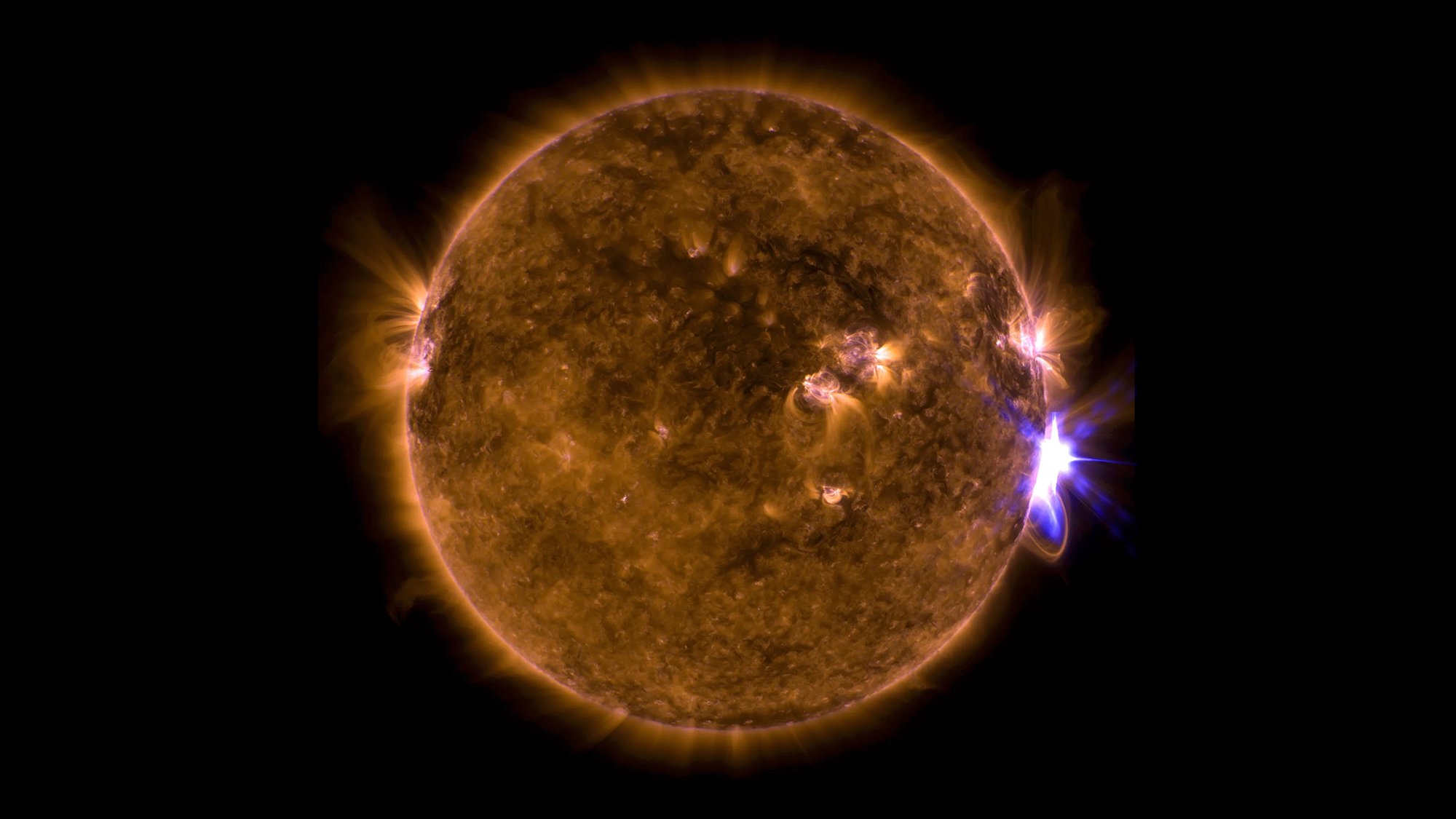

What Carrington

and the awestruck people of the subtropical Atlantic saw were related. The

aurora was a result of the most intense solar storm in recorded history, now

called the Carrington Event. These solar storms can send out large clouds of

electrified gas and dust at up to two million miles per hour. If and when these

particles reach Earth, it can disrupt and distort Earth’s magnetic field.

The Carrington

Event was so large that these particles interacting with Earth’s magnetic field

impacted telecommunications.

“There were

sparks that were so intense that the wires caught fire, in some places,” says

Hudson. “Some of the telegraph operators were shocked and burnt. When you

connect the long wires together for power distribution, you’re asking for

trouble when surges like that happen.”

Engineers have

since learned a great deal about how to handle those large wires since the

Carrington Event. However, our reliance on electricity has only grown

exponentially. A flare of similar–or even greater like Miyake Events–magnitude

still could happen and the effects are of major interest to sci-fi aficionados

and scientists alike. With so much more technology at risk than just the

telegraph wires of the Nineteenth Century, the effects could be catastrophic.

“In a world that

is now so dependent on electricity and electronics, a similar event has the

potential to cause widespread disruptions and damage to the electronics aboard

Earth-orbiting satellites, ground-based electronics, and the power grid,” Alex

Gianninas, an astrophysicist at Connecticut College tells Popular Science.

Our in-space

infrastructure, such as, telecommunication satellites are also particularly

vulnerable to the Sun’s coronal mass ejections (CME). CMEs are large eruptions

at the surface of the Sun that shoot charge particles out into space. All of

that energy from the particles can degrade solar panels, damage navigation

systems, and alter orbital paths, potentially causing mass collisions and

excess space debris.

While there is

constant activity happening on the surface of the Sun, there are generally more

low intensity flares than higher intensity ones. The sunspot activity that

creates these storms and flares also rises and falls on a roughly 11-year

cycle. This year, we are heading into the maximum level of this cycle. Larger

solar storms are most likely to occur during solar maximum, sometimes with several

per day. During solar minima, these can pop up less than one per week.

“Geomagnetic

storms, and more specifically, the CMEs that cause them, increase in frequency

and intensity as the solar cycle reaches its maximum,” says Gianninas. “We are

currently in Solar Cycle 25 and are still heading toward the maximum, which is

predicted to occur this coming summer, likely in July.”

While some

scientists estimate that the chances of a solar storm like the Carrington Event

happening in the next century are at 12 percent or less, it is still a threat

to be taken seriously. Currently, an array of satellites are constantly

monitoring the Sun. These include the Geostationary Operational Environmental

Satellite (GOES), the two Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory satellites

(STEREO-A and -B), the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). These send back data

and images in both visible and invisible light, so we can see a wide range of

activity.

According to

Gianninas, it can take between several hours and a few days for the particles

from a CME to reach Earth, so there is some advance warning that something is

coming. NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center also tracks all of this activity

and can be a good resource for determining where and when the aurora might be

visible. This can give utility companies, satellite operators, and crew aboard

the International Space Station some time to prepare their systems for impact.

For the general public, there is not too much to do beyond charging up devices

and making sure you have general emergency supplies like water, batteries, and

flashlights..

For scientists

and citizen scientists alike, this combination of potential doom and the big

questions about our origins are part of what makes studying this solar activity

so exciting.

“People are so

fascinated by the origin of life and the fundamental questions that the stars

inspire in us,” says Hudson. “I think the Sun is in the same category. It’s

just something very close by and familiar and yet we have eclipses and strange

things happen. So it’s not surprising that 10-year-olds can be amazed by the

same thing as adults.”

December

19, 2024

Harri

Weber

The

sun is a singular experience in Earthly life. We see it. We feel it. But we

can’t seem to hear it.

If

we did, would it sound like an explosion? Or a primordial heartbeat? Or just a

dull roar, bellowing 93 million miles away? The sun is huge—roughly 100 times

wider than Earth, and it’s especially active lately—so much so that its

eruptions can distort GPS, degrade communications, and create auroras. So

what’s with the silent treatment? These questions and more cascade from a

Popular Science reader’s seemingly simple ask: Does the sun make noise?

“The

basic answer is no, not for us,” Chris Impey, an astronomer and professor at

the University of Arizona, said in a call with Popular Science. “The sun

doesn’t make noise because noise, or sound, needs a medium to carry it,” Impey

explained. Essentially, the space “between us and the sun is almost a perfect

vacuum, so sound can’t travel through that.” Impey added, “So whatever the sun

is doing, it’s not transmitting sound to us.”

Bummer!

Or… great! Maybe we’re fortunate to not hear the big plasma ball, but with

virtually nothing in the way, how come sound doesn’t travel past the emptiness

to our ear drums?

“Sound

is so funny. It’s a pressure wave,” explained Shauna Edson, an astronomy

educator at the National Air and Space Museum in D.C. “It has to move through

something, and our ears are adapted to interpret those pressure waves and turn

them into a sound that our brain can understand.” To help people visualize how

sound works, Edson said she asks them to imagine a row of beach balls.

“If

you pushed on the ball at the end of the line, it would roll into the next

ball, which would bump into the next ball, and they would all kind of—boom,

boom, boom,” she explained. “The push would travel from ball to ball, all the

way down the line, as a wave. That is what sound does to the molecules of air

or liquid or solid that they’re moving through.” In space, the molecules are

“so few and far between,” Edson said, “that even if you pushed on one, there’s

nothing else nearby for it to push on, so the wave can’t keep going.” (Hence,

the famous Alien tagline, “In space no one can hear you scream.”)

So,

the sun can’t make sound as we conceptualize it on Earth because of the vacuum

of space. But still, given how big and energetic it is, isn’t the sun doing

something that’s at least sound-like?

“The

sun has oscillations and vibrations,” offered Impey, “so in a sense, it does

have some of the elements of sound within it.” But even so, because the sun is

so large relative to Earth, “all the activity in [it] is incredibly

low-frequency,” Impey said. In other words, sun activity is definitely not the

sort of thing human ears evolved to perceive. Cool—but why, then, are there

audio clips online offering otherworldly snippets of oscillations or solar

winds via Stanford and Johns Hopkins? This is where something called

sonification comes in.

“It’s

quite a clever idea in science, where you take—in astronomy particularly—you

take some distant phenomenon, like a galaxy; or a black hole, you know, sucking

in matter; or the atmospheric motions of Jupiter; or the sun itself, and you

turn the signals that are happening in that domain into sound waves, just as a

way of realizing them in a way that’s not visual,” Impey said. The technique

helps scientists represent data, but according to Impey it also “sort of

misrepresents the physics. It’s not a real sound.”

Impey

elaborated that sonification is sort of like viewing a vivid infrared image

from the James Webb Space Telescope on your phone screen. “They’re not real

colors because the radiation that was being detected was not visible to the

naked eye.”

Back

to sonification: “It’s a way of experiencing a phenomenon that’s not really for

the human senses at all,” explained Impey.

There

are some good reasons why experts turn to sound to help them interpret such raw

data. “Sound is one of the ways that humans make sense of our environment,”

said Edson.

“We

might hear raindrops or wind blowing, and that tells us about the weather

without us needing to look outside. We hear ambulance sirens that tell us we

need to get out of the way.” Edson said, “But sound is also a way of learning.”

Like a mechanic listens to an engine, or a doctor listens to a heart, for

anomalies, scientists convert and condense data into sound to figure out what’s

happening. “You can hear years and years of changes in a few seconds or

minutes,” Edson explained, and “sometimes there are patterns that will show up

in the sound that you wouldn’t have noticed.”

Like

Earth, our sun has its own activity cycle. And it’s been quite busy lately.

“Right now we’re in what we call solar maximum,” said Edson. “So there’s a ton

of sunspots. There are lots of flares. We’ve been seeing auroras in places we

don’t usually.”

If

you sonify the sunspot data, “when it gets turned into sound, you can hear the

up and down of that 11-year cycle,” explained Edson, “and it does kind of sound

like a heartbeat.”

(The

expert did not say if it went something like ba boom ba boom, or lub dub lub

dub.)

No comments:

Post a Comment