Jamal Kanj

This is a review

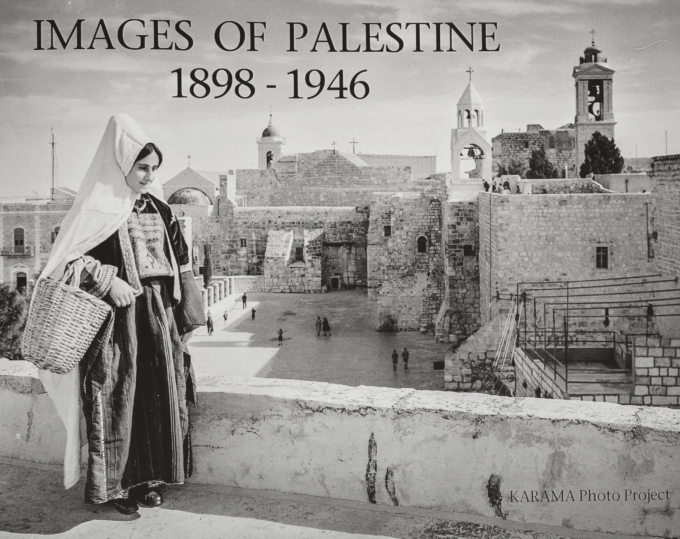

of an exceptional photobook, Images of Palestine (1898-1946). The book is a

collection of photographs that spans nearly five decades, captured in the

period leading up to the Palestine Nakba. Together, these black-and-white

images chronicle a vibrant and diverse Palestinian society, highlighting its

connection to the land, its achievements in commerce, architecture, and civil

society, and its development into a modern socio-political entity chafing to

break free from colonial domination.

The photographs

cover the final years of the Ottoman Empire, World War I, the establishment of

the British Mandate of Palestine, the large-scale European Jewish immigration

under the British colonial rule, and the emergence of a popular movement for

Palestinian independence.

The

photographers were members of the American Colony Photo Department and

employees of the Photo Department’s successor, the Matson Photographic Service.

The American Colony was a Christian utopian community founded in Jerusalem in

1871. Its members began taking photographs in the late 1890’s, eventually

developing a full-fledged photographic division. In the 1940’s, the American

Colony ceased to exist as a religious community, but the photographic work was

continued by Colony member G. Eric Matson under the name Matson Photographic

Service.

More than 23,000

glass and film negatives, transparencies, and photographic prints created by

the American Colony Photo Department and the Matson Photo Service were

transferred to the Library of Congress between 1966 and 1981. Since then, the

images have been digitized for archival preservation by the Library of

Congress.

The American

Colony did not set out to document the emergence of modern Palestine through

its photographs. Instead, its efforts were driven by a religious utopian

vision. Composed of American and Swedish immigrants living in Jerusalem, the

Colony’s work was deeply influenced by this vision, as well as by the

Orientalist perspectives its members carried with them. These influences are

evident in both their choice of photographic subjects and the descriptions

accompanying the images in their archives.

The photobook is

divided into eight galleries, each designed to highlight a unique and integral

aspect of the pre 1948 vibrant Palestinian societal structure. The galleries

serve as a visual narrative, weaving together the diverse cultural, social, and

economic elements that define the collective community. Each segment focuses on

specific themes, such as City Life, Commercial, Education, Landscape, Medical,

Colonialism and Resistance, Palestine Broadcast Service and Individual

Portraits, creating a comprehensive portrayal of the dynamic interplay within

the society. This structured approach provides a glimpse into an aspect of

Palestinian life, enabling viewers to appreciate the richness and depth of the

community’s identity through a curated lens, delivering a meaningful and

immersive experience.

During the

period when these photos were taken, Palestinians endured three distinct forms

of foreign intervention: the Ottoman Empire, the British Mandate, and the large

European Jewish immigration supported by British colonial authorities, aimed at

transforming Palestine into a new political and social entity. This was

combined with the emergence of a popular movement for Palestinian independence.

The interplay

between external interventions and indigenous social and economic structures,

along with the resulting conflicts, is vividly depicted in the stories these

photographs convey. However, these stories are not bound to a single moment in

history. Instead, they are part of an ongoing historical continuum. The

underlying dynamics that shaped them persist, with their narratives continuing

to evolve and unfold visibly in the present day.

While

Palestinian society during this period was often described as “traditional” by

external observers, the photographs reveal a sophisticated social fabric.

Palestinian cities boasted thriving marketplaces, diverse religious and

cultural communities, and connections to regional and international trade

networks. Intellectual life flourished in urban centers, with schools, mosques,

churches, and libraries serving as vibrant hubs of education and cultural

exchange. This blend of tradition and modernity highlighted the resilience and

adaptability of Palestinian society in navigating external interventions and

shifting historical dynamics.

The over 200

large size page photobook was produced by KARAMA (www.karamanow.org), San

Diego, California, an independent non-profit organization dedicated to

promoting understanding of the Arab and Islamic world, with a particular focus

on Palestine. KARAMA launched its Palestine Photography Project in 2015,

believing that distributing high-quality photographs of life in Palestine prior

to 1948 could effectively convey the dignity, humanity, and cultural richness

of the Palestinian people.

In addition to

the photobook, the Palestine Photography Project has created a portable

“Museum-in-a-Box,” featuring selected photographs from the book, designed for

tabletop display at community events. The photobook and the Museum-in-a-Box, as

well as individual prints of the photos, can be ordered from

www.PalestinePhotoProject.org.

Images of

Palestine (1898-1946) is a must have coffee table book!

Ramzy

Baroud

The

problem with political analysis is that it often lacks historical perspective

and is mostly limited to recent events.

The

current analysis of the Israeli war on Gaza falls victim to this narrow

thinking. The ceasefire agreement, signed between Palestinian groups and Israel

under Egyptian, Qatari, and US mediation in Doha on January 15, is one example.

Some

analysts, including many from the region, insist on framing the outcome of the

war as a direct result of Israel’s political dynamics. They argue that Israel’s

political crisis is the main reason the country failed to achieve its declared

and undeclared war objectives—namely, gaining total “security control” over

Gaza and ethnically cleansing its population.

However,

this analysis assumes that the decision to go to war or not is entirely in

Israel’s hands. It continues to elevate Israel’s role as the only entity

capable of shaping political outcomes in the region, even when those outcomes

do not favor Israel.

Another

group of analysts focuses entirely on the American factor, claiming that the

decision to end the war ultimately rested with the White House. Shortly after

the ceasefire was officially declared in Gaza, a pan-Arab TV channel asked a

group of experts whether it was the Biden or Trump administration that deserved

credit for supposedly “pressuring Israel” to agree to a ceasefire.

Some

argue that it was Trump’s envoy to Israel, Steve Witkoff, who denied Israeli

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu any room to maneuver, thus forcing him,

albeit reluctantly, to accept the ceasefire terms.

Others

counter by saying that the agreement was initially presented by the Biden

administration. They argue that Biden’s supposedly active diplomacy ultimately

led to the ceasefire.

The

latter group fails to acknowledge that it was Biden’s unconditional support for

Israel that sustained the war. His UN envoy’s constant rejection of ceasefire

calls at the Security Council made international efforts to stop the war

irrelevant.

The

former group, however, ignores the fact that Israeli society was already at a

breaking point. The war on Gaza had proven unwinnable. This means that, whether

Trump pressured Netanyahu or not, the outcome of the war was already sealed.

Continuing the war would have meant the implosion of Israeli society.

On

the Palestinian side, some analyses—affiliated with one faction or

another—exploit the war’s outcome for political gain. This type of thinking is

extremely insensitive and must be wholly rejected.

There

are also those hoping to play a role in Gaza’s reconstruction to gain political

and financial leverage and increase their influence. This is a shameful stance,

given the total destruction of Gaza and the urgent need to recover the

thousands of bodies trapped under rubble, as well as to heal the wounded and

the population as a whole.

One

thing all these analyses overlook is that Israel failed in Gaza because the

population of Gaza proved unbreakable. Such notions are often neglected in

mainstream political discussions, which tend to commit to an elitist line. This

line is entirely removed from the daily struggles and collective choices of

ordinary people, even when they achieve extraordinary feats.

Gaza’s

history is one of both pain and pride. It stretches back to ancient

civilizations and includes great resistance against invasion, such as the

three-month siege by Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army in 332 BCE.

Back

then, Gazans resisted and endured for months before their leader, Batis, was

captured, tortured to death, and the city was sacked.

This

legendary resilience and sumoud (steadfastness) proved crucial in numerous

other fights against foreign invaders, including resistance to Napoleon

Bonaparte’s army in 1799.

Even

if some of Gaza’s current population is unaware of that history, they are a

direct product of it. From this perspective, neither Israeli political

dynamics, the change of the US administration, nor any other factor is

relevant.

This

is known as “long history” or longue durée. Far from being merely an academic

concept, the long legacy of resistance against injustice has shaped the

collective mindset of the Palestinian population in Gaza over the years. How

else can we explain how a small, isolated, and impoverished population, living

in such a tiny piece of land, managed to withstand firepower equivalent to many

nuclear bombs?

The

war ended because Gaza withstood it—not because of the kindness of an American

president. It is crucial that we emphasize this point repeatedly, rather than

seeking inconclusive and irrational answers.

It

matters little how we define victory and defeat for a nation still suffering

the consequences of a war of annihilation. However, it is important to

recognize that Palestinians in Gaza stood their ground, despite immense losses,

and prevailed. This can only be credited to them—a nation that has historically

proven unbreakable. This truth, rooted in “long history,” remains valid today.

Reza Behnam

The world has

focused its attention on the humanitarian pause and exchange of prisoners in

Gaza that began on 19 January.

Meanwhile, Israel has trained its immense military power and insanity on

the defenseless occupied West Bank.

Palestinians there are now facing some of the same cruelty that Israel

has been inflicting on their countrymen and women in the Strip for 15 horrific

months.

As Israel has

temporarily halted its bombing of Gaza and scaled up its ongoing violence and

annexation plans in the West Bank, the instructive lessons imparted in the

fable of “The Scorpion and the Frog,” popular in the Middle East, hold

relevance: “A scorpion pleasantly asks a

frog to carry him over a river. The frog is afraid of being stung, but the

scorpion argues that if it did so, both would sink and the scorpion would drown. The frog then

agrees, but midway across the river the scorpion does indeed sting the frog,

dooming them both. When asked why, the scorpion replies, it is simply in my

nature.”

Islamic

resistance groups, like Hamas, know not to expect Israel to be other than what

it is, that the Zionists in control are incapable of transformation and

trust. Confronted with Israel’s

overwhelming power to destroy, they know not to be persuaded by its

promises. In the end, a scorpion remains

a scorpion.

For Israel and

the United States, both equally untrustworthy, the allegory is particularly

poignant. Washington has fed Israel’s

addiction to power by never

demanding

anything from its proxy. It has never

asked it to renounce violence, to stop killing civilians, to end the

occupation, to demilitarize and to observe international and humanitarian laws. It has essentially helped create a deformed

body politic, whose future is uncertain.

Israel has for

decades ridden on the back of the United States to the misfortune of both

countries. Without Western affirmation

and financial sustenance—first British then American—there would be no country

called Israel.

Israel’s early

European founders envisioned the Jewish state as a rampart of the West against

Asia. They believed that the support of

a great power was essential to Zionism’s success. As Zionist founding father, Austro-Hungarian

Theodor Herzl, wrote in 1896, the “The State of the Jews” would serve as “an

outpost of civilization against barbarism” — a supremacist, racist attitude

that prevails in Israel to this day.

The alignment of

U.S.-Israeli interests began in the early 20th century when President Woodrow

Wilson (1913-1921) approved the Balfour Declaration, promising his support for

the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, before

it was publicly announced by the British government in 1917.

Chaim Weizmann,

Israel’s first president, was especially pivotal in securing President Harry S.

Truman’s early recognition of the newly established state of Israel on 14 May

1948, and in fundraising in the United States.

His lobbying

efforts included a partisan essay, “Zionism—Alive and Triumphant,” printed in

the 12 March 1924 edition of The Nation magazine. In it he wrote, “Political Zionism, in brief,

is the creation of circumstances favorable to Jewish settlement in Palestine….

The larger the Jewish settlement the greater the ease with which it can be

increased, the less the external opposition to its increase; the smaller the

Jewish settlement in Palestine the more difficult its increase, the more

obstinate the opposition.”

In addition,

letters between Weizmann and President Truman, as well as their 18 March 1948

meeting in the White House were important in securing the president’s support

for and validation of a Jewish state in Palestine, against the advice of his

own State Department.

In the words of

Israel’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Danny Danon: “From the moment President Truman became the

first world leader to recognize the Jewish state, Israel has had no better

friend than the United States of America, and the U.S. has had no more

steadfast ally than the state of Israel.”

The United

States persists in believing that it can dictate the fate of Palestinians and that Israel can continue its role as

colonizer of Palestine and as America’s bullyboy in the Middle East.

Clearly, there

are no guarantees of peace with justice in the current Gaza ceasefire

plan. Political Zionism was built on the

colonial idea that Jewish rights—their right to self-determination—outweighed

the rights of indigenous Palestinians.

Within days of

announcing the ceasefire, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stressed that it

was temporary and that Israel reserved the right to return to “war” on Gaza

should negotiations on the second phase of the agreement prove futile. Manufacturing “futility” should prove easy

for a regime well practiced in deception for over half a century. He also stated that he had received

assurances of U.S. support from outgoing President Joe Biden and President

Donald Trump.

In addition, two

days after the ceasefire was in place, Israel stepped up its brutal air and

ground assault on the occupied West Bank.

Since October

2023, across the West Bank, at least 870 Palestinians, including 177 children,

have been killed and more than 6,700 wounded in attacks by the Israeli army and

Israeli squatters (“settlers”). The

Jenin refugee camp is now nearly uninhabitable and an estimated 2,000 residents

have been forced from their homes in the Jenin area.

It must be

emphasized that Israel’s militarism in Gaza and the West Bank are illegal under

international law. We should also

remember that on 19 July 2024, the International Court of Justice determined

that Israel’s occupation in the Palestinian territories since 1967 and

subsequent Israeli “settlements” and exploitation of natural resources are

unlawful and must end.

The essence of

the current ceasefire was rightly expressed by Agnes Callamard, Secretary

General of Amnesty International:

“Unless the root causes of this ‘conflict’ are addressed, Palestinians

and Israelis cannot even begin to hope for a brighter future built on rights,

equality and justice.”

International

law is on the side of the resistance. The Geneva Conventions of 1949 support

the right of self-determination for occupied people, including the right to

resist.

Dr. Basem Naim,

senior member of Hamas’s political bureau, laid out the group’s position to

hold up its end of the agreement, stating: “We are not looking for a fight. We

are looking [at] how to protect the future of our children.” He also noted that

a political solution would be preferable, but if not, “then all Palestinians

are still ready to continue their struggle,” adding, “We believe this is a just

cause, a just struggle and we have all the guaranteed right by international

law to resist the occupation by all means, including armed resistance.”

For the people

of Gaza, the six-week ceasefire has brought some hope mixed with

melancholy. Thousands have been

searching in the rubble to find and bury their loved ones. In the Muslim umma (community), burials are

customarily carried out within a day.

The daily fight for survival and with cemeteries pulverized by Israeli

bombs, Palestinians have been deprived of their right to bereavement, to

observe cultural rituals and religious burial rites.

Palestinian

life, since the arrival of European Zionists, has been replete with struggle,

resistance and grief. The resiliency to

free themselves from the yoke and sting of colonialism is, however, forever

etched in the rubble of Gaza.

No comments:

Post a Comment