Reza Talebi

( Global Voices

) – My grandfather was a farmer near Lake Urmia in northwestern Iran. Once the

largest lake in Iran, it is now a salt-ridden desert. When the water vanished,

his wheat fields dried up. Salt crept over the land, swallowing everything. He

died — not suddenly, but slowly.

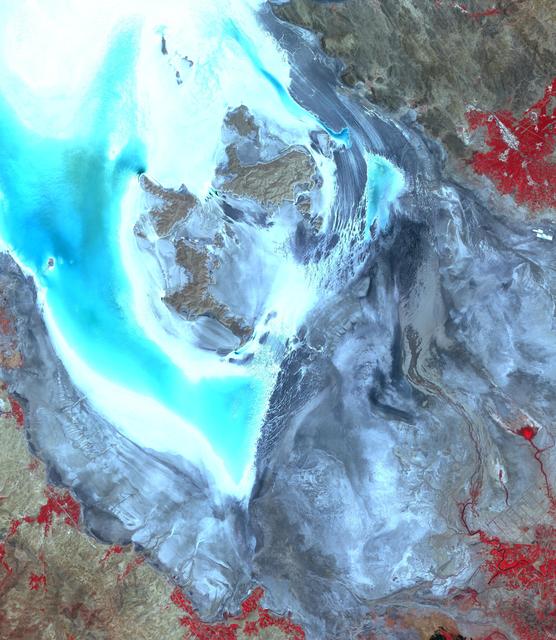

Lake Urmia, Iran. Public Domain. NASA.

We watched a man who had fathered generations

crumble under the weight of thirst. He fled to Hamadan, chasing water, but lost

everything — his land, his life, and the water he sought.

While the world

fixates on Iran’s nuclear ambitions or internet controls, a quieter and

deadlier threat has been unfolding for decades: water scarcity. This crisis is

not simply about drought but the result of decades of mismanagement,

overextraction, and disregard. Iran is now teetering on the edge of social and

ecological collapse.

From the drying

wetlands of Gavkhouni to mass migration toward the north, water has become more

than an environmental issue — it’s a fault line of ethnic, political, and

economic tension transforming Iran’s geography, demographics, and stability.

Iran’s water

crisis: A looming catastrophe

Mohammad

Bazargan, secretary of the Water and Environment Task Force in Iran’s

Expediency Council, recently warned that we are dangerously close to a

full-blown water and soil disaster. He said we may soon reach a point where

“there won’t be enough room for people to sleep, let alone enough food to eat.”

Internal

climate migration is already underway. Villages in arid regions have emptied

out. Families forced to abandon homes aren’t seen as refugees, but they are —

climate refugees. This slow, creeping exodus has been unfolding for years,

largely ignored by decision-makers more focused on social media censorship than

survival.

The problem is

not just poor management, but a flawed philosophy: domination over nature

rather than stewardship. Iran’s water laws, like the Law of Equitable Water

Distribution, remain mostly on paper. Successive governments have approached

water as something to be controlled and owned, resulting in depleted aquifers,

dry rivers, and failing ecosystems.

Agronomist

Abbas Keshavarz estimates that Iran has overdrawn its groundwater reserves by

150 to 350 billion cubic meters. Mohammad Hossein Bazargan places irreversible

groundwater loss at 50 billion cubic meters over 150 years — water that will

never be replenished. Regardless of the figure, both agree: the country is

running dry.

Mismanagement

and policy failures

Older

generations viewed water scarcity as seasonal. If a river ran low, it was

blamed on rainfall. But today, even with increased inflows — like the Zayandeh

Rud River flowing more now than in the Safavid era — no water reaches the

wetlands. The issue isn’t inflow, it’s excessive consumption.

Former

Environment Department head Issa Kalantari warned in 2014 that Iran had 15

years of water left for agriculture. That leaves just four years. Iran’s

rainfall has remained relatively stable, but underground reserves — fossil

waters that take millennia to refill — have been drained at breakneck speed.

Ancient “qanat” systems were abandoned for deep wells. Oil wealth ushered in a

mindset of extraction and short-term gains.

Out of Iran’s

original 500 billion cubic meters of fossil water, 200 billion are gone. The

remaining 300 billion are saline, unusable for agriculture. Yet agricultural

practices remain wasteful: around 70–90 percent of Iran’s usable water goes to

farming, with irrigation efficiency at only 30 percent, compared to 50 percent

in Turkey or Iraq. Up to 50 billion cubic meters of water is wasted each year.

Urban areas

aren’t spared. Cities lose 25–30 percent of their water because of leaks,

mismanagement, and outdated infrastructure. By contrast, cities in the global

north lose under 10 percent. In many cities, potable water is still used to

irrigate green spaces instead of treated wastewater. Meanwhile, industries like

Mobarakeh Steel consume 210 million cubic meters of water annually — more than

entire provinces.

Iran’s

dam-building spree hasn’t helped. In 2012, there were 316 dams; by 2018, that

number surged to 647. Many were built without environmental assessments and for

political or military purposes. The Latyan Dam near Tehran, once holding 95

million cubic meters, now holds just 9 million. Groundwater levels in Tehran

have dropped by 12 meters in two decades, causing land subsidence and

destabilizing urban areas.

Military-linked

companies, especially those tied to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

(IRGC), have seized lands near Lake Urmia, cultivating high-water crops like

watermelon. Producing one kilogram of watermelon consumes 250 liters of water —

yet it remains cheap. Some say Iran offers the “cheapest water in the world,”

but at what cost?

Ethno-hydrological

and climatic fault lines in Iran

Provinces like

Khuzestan and Lorestan are now at the heart of water-related ethnic tensions.

In Lorestan, Lur communities accuse the Persian-majority city of Isfahan of

“stealing” water through projects like the Koohrang and Beheshtabad canals.

These transfers have sparked protests, online backlash, and accusations of

“Arab cleansing.”

Mahmoud

Ahmadinejad’s government tried to appease protestors by allowing unregulated

well drilling, worsening the crisis. In Khuzestan, Arab communities accuse the

state of favoring Lurs by diverting the Karun River. The Koohrang-3 tunnel

submerged entire villages, displacing people and inflaming tensions.

In the

northwest, Lake Urmia — shared between Kurdish and Turkish-speaking populations

— has dried to a salt crust. The Zab River transfer project, meant to revive

the lake, has fueled disputes between Kurdish and Turkish communities.

Ethno-demographic shifts are already evident as Azeris migrate to Tehran and

Kurds move into Urmia.

Other

megaprojects, like transferring water from the Caspian Sea or Oman Sea, are

criticized as ecologically destructive and serving industrial elites rather

than public need. These projects highlight the government’s reliance on

unsustainable, grandiose solutions instead of real reform.

Meanwhile, the

government securitizes dissent. Environmental protests are met with repression.

Officials rarely speak out while in office. When they do, it’s often too late.

Iran’s water

crisis has also spilled across borders — into disputes with Afghanistan, Iraq,

Turkey, and Azerbaijan. But the core of the crisis remains internal: a state

model unable to listen, adapt, or act.

More than 280

cities face extreme water stress. Rainfall has dropped by over 50 percent in

some provinces. Iran ranks fourth globally for water scarcity risk. The country

is inching toward “Day Zero,” when taps may run dry completely.

Water is the

blood of the earth. It connects people across divides, yet in Iran, it is

tearing communities apart. As the rivers vanish, so too do trust, stability,

and cohesion. Ethnic tensions, economic despair, and climate migration are

converging. The silence surrounding this crisis is deafening.

If ignored,

water, not war, may become Iran’s greatest existential threat.

No comments:

Post a Comment